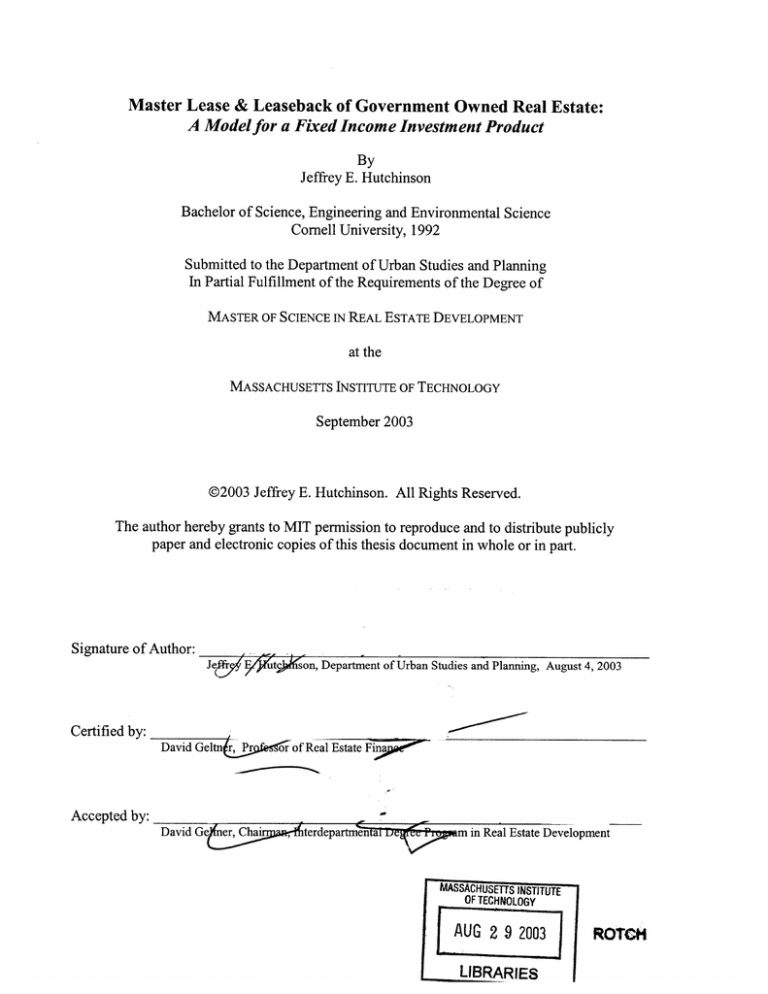

Master Lease & Leaseback of Government Owned Real Estate:

A Model for a Fixed Income Investment Product

By

Jeffrey E. Hutchinson

Bachelor of Science, Engineering and Environmental Science

Cornell University, 1992

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

September 2003

@2003 Jeffrey E. Hutchinson. All Rights Reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly

paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author:

Je&

F

David Geltn

Pr

David Ge

Cterdepartm

ute

son, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, August 4, 2003

Certified by:

Real Estate F n

Accepted by:

in Real Estate Development

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

AUG 2 9 2003

LIBRARIES

ROTCH

Master Lease & Leaseback of Government Owned Real Estate:

A Model for a Fixed Income Investment Product

By

Jeffrey E. Hutchinson

Bachelor of Science, Engineering and Environmental Science

Cornell University, 1992

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

August 4, 2003

@2003 Jeffrey E. Hutchinson. All Rights Reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly

paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Signature of Author:

ffrof

(Tionson,Department of Urban Studies and Planning,

August 4, 2003

Certified by:

David GefIe-r, Professor of Real Esta

ce, August 4, 2003

Accepted by:

David Geltner, Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development

August 4, 2003

Master Lease & Leaseback of Government Owned Real Estate:

A Model for a Fixed Income Investment Product

By

Jeffrey E. Hutchinson

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 4, 2003

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE INREAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

ABSTRACT:

Throughout the United States, significant taxpayer capital is unnecessarily tied up in the ownership of

state and municipal government buildings. Today, multiple state and municipal governments face record

budget deficits, and are struggling to find ways to raise revenues and decrease annual operating costs in

order to close these budget gaps. At the same time, substantial amounts of investor capital from both

public and institutional funds, as well as private investors, sits idle, as there is a lack of opportunity for

safe, moderate-return long-term investments in today's markets.

This thesis investigates the benefits and drawbacks to an investment structure, similar to the commonly

used corporate sale-leaseback, that can be used to free capital that is tied up in existing governmentowned real estate, while allowing governments to retain long-term ownership of these assets. It also

presents the methodology for syndicating these investments into rate-able fixed income products, similar

to municipal bonds or CMBS. These investments and the associated participation instruments create

arbitrage opportunities for underwriters and syndicators of Government Lease Backed investments, and

generate capital flows in the tens of billions of dollars.

The models presented may be applied to federal, state and municipal government assets alike. However,

this thesis focuses on the application of the models to assets owned by the State of California, as it

currently has one of the most significant budget crises in the country, as well as the largest state-owned

real estate portfolio.

Thesis Supervisor:

Professor David Geltner

Title: Professor of Real Estate Finance

Master Lease & Leaseback of Government Owned Real Estate:

A Model for a Fixed Income Investment Product

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IN TROD U C TION ..............................................................................................................................

4

GOVERNM ENT-OW NED REAL ESTATE.......................................................................................................................4

CURRENT BUDGET DEFICITS.....................................................................................................................................4

CAPITAL M ARKET CONDITIONS ................................................................................................................................

THE M ASTER LEASE & LEASEBACK SOLUTION.........................................................................................................6

STATE OF CALIFORNIA ..............................................................................................................................................

5

.

7

STA TE OW NED RE A L E STA TE ....................................................................................................

8

OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................

D OES THE PORTFOLIO FIT THE M ISSION? ..................................................................................................................

A DVANTAGES OF STATE OWNERSHIP........................................................................................................................9

D ISADVANTAGES OF STATE OWNERSHIP...................................................................................................................9

KEY CONSIDERATIONS - SELL VS. HOLD VS. LEASE............................................................

8

8

II.

10

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL..............................................................13

III.

OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................................................................................

SELLER BENEFITS:...................................................................................................................................................15

SELLER D ISADVANTAGES........................................................................................................................................

BUYER A DVANTAGES..............................................................................................................................................

BUYER D ISADVANTAGES ........................................................................................................................................

M ASTER LEASE VERSUS SALE .................................................................................................................................

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL ...................................................................

IV.

13

17

18

19

20

22

THE M ASTER LEASEHOLD INTEREST.......................................................................................................................22

THE GOVERNMENT LEASEBACK..............................................................................................................................23

VALUATION AND PROCEEDS....................................................................................................................................25

RATING THE LEASE INVESTM ENT .........................................................................................

V.

CATEGORIZATION OF LEASES ..................................................................................................................................

STATE CREDITWORTHINESS....................................................................................................................................28

ESSENTIALITY OF THE FACILITY..............................................................................................................................29

SECURITY FEATURES...............................................................................................................................................29

27

27

A SA MPLE TRA N SA C TION .....................................................................................................

31

PROPOSED LEASE TERM S ........................................................................................................................................

V ALUATION.............................................................................................................................................................34

UNDERW RITING, SYNDICATION & ARBITRAGE....................................................................................................

......................

SUM MARY ......................................................................................................................................

31

V I.

V II.

T HE C A LIFORN IA MA RKET ..................................................................................................

CALIFORNIA'S REAL ESTATE PORTFOLIO................................................................................................................38

H ISTORY OF SYNDICATION .....................................................................................................................................

OUTSTANDING ST ATE D EBT ....................................................................................................................................

35

36

38

38

39

VIII.

C ON C LU SION .............................................................................................................................

41

IX.

A PPE ND ICE S ..............................................................................................................................

43

BIB LIO GR A PHY .............................................................................................................................

51

X.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER1.

CHAPTER I.

I.

INTRODUCTION

GOVERNMENT-OWNED REAL ESTATE

The US Federal Government, nearly all state governments, and hundreds of municipal governments

collectively own and operate many millions of square feet of real estate throughout the country. The

Federal Government, through the General Services Administration (GSA) owns 330 Million square feet

in 1,700 buildings throughout the country '. The three most populated states; California, Texas and New

York collectively own over 129 Million square feet of Space in more than 17,000 buildings, as outlined

below:

Table 1. - State-Owned Real Estate Portfolios

California, Texas and New York

Square Feet

102,085,726

9,955,213

17,700,000

+129,000,000

Buildings

16,955

70

126

+17,000

State

California

Texas

New York

Total:

Does not include holdings associated with State University Systems.

Sources: CA and NY Depts. of General Services, Texas Building and Procurement Division, July 2003.

In many cases, it can be argued that the ownership and operation of these facilities is not critical to the

mission of the various governments in providing services to their constituents, and that the ongoing cost

of financing and operating these depreciating assets is not an advantageous use of taxpayer dollars.

CURRENT BUDGET DEFICITS

Currently the US Federal and many state governments are facing significant budgetary crises, as

operating deficits exceed many billions of dollars:

Table 2.

Federal and State Budget Deficits Fiscal Year 2003-04

US Federal

California

New York

Texas

$307 Billion

$38.0 Billion

$9.3 Billion

$3.6 Billion

Sources: White House, CA, NY & TX State Government Web Sites.

US General Services Administration, Public Buildings Service.

PAGE 4

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I.

As illustrated, the State of California faces one of the largest budget gaps in the nation, with a projected

shortfall exceeding $38 Billion for fiscal year 2003-2004. Issuing General Obligation (GO) bonds, to

borrow money from the fixed income markets, has traditionally been a method that the State has

employed to bridge budgetary shortfalls. However, with outstanding GO commitments of more than

$25.0 Billion 2, the State is reaching its bonding capacity.

To exacerbate this problem, California's GO bond rating was downgraded to BBB- by Standard & Poors

during the week of July

2 1s',

2003, only one step above junk bond status. This not only hinders the

State's ability to finance the deficit with GO bonds, but increases the cost of doing so substantially.

As a result of these conditions, legislators face making significant cuts in government programs and

services, as well as raising taxes and fees for services, placing further financial burdens their constituents.

CAPITAL MARKET CONDITIONS

While these enormous government-owned real estate portfolios remain un-leveraged and government

budget deficits continue to hurt taxpayers, substantial investor capital remains sidelined, as there are few

opportunities for secure, moderate-return, long-term investments.

With the fallout in global stock markets since the spring of 2000, the current recession in the US, and

continued recession in large foreign markets such as Japan, there has been a 'flight to quality' of investor

capital. Seeking lower risk, investors have focused on more stable assets such as real estate or fixed

income products such as treasuries and municipal bonds.

However, fixed income investments have lust much of their luster.

As the Federal Treasury has

continually cut the Prime Lending Rate in an attempt to stimulate the faltering economy, yields on federal

treasury and municipal bonds have correspondingly decreased to historic lows. Historic yields on various

US Treasury securities are illustrated in the following figure.

2

California State Treasurer's Office, June 2003.

PAGE 5

INTRODUCTION

I.

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

F.iu1THtiUTarYl

Figure 1. - Historic US Treasury Yields

Source: US Federal Treasury, July 2003.

As we approach what many experts see as the 'bottom' of the yield curve, and interest rates seemingly

have nowhere to go but up, investors face increasing interest rate risk in their fixed income portfolios.

Additionally, competition for quality real estate investments is fierce. In the United States, which has one

of the world's largest, most sophisticated and most transparent real estate investment markets, yields have

been driven down by decreasing interest rates as well as a glut of capital investor capital. As many

frustrated real estate investment experts have said, "There is too much money chasing too few good

deals."

THE MASTER LEASE & LEASEBACK SOLUTION

As CFOs and treasurers of corporations, non-profits and NGO's have employed sale-leaseback structures

to free-up capital for more mission critical uses, state and municipal governments can employ similar

structures to leverage their existing real estate assets and generate revenues to finance critical government

programs or new capital projects.

The Master-Leaseback transaction closely follows the structure of the sale-leaseback. However, instead

of purchasing the fee-simple interest in the property, the investor purchases a master leasehold interest,

which corresponds to the term of a sublease of the property by the government. As described in detail

throughout this thesis, this structure provides several benefits for taxpayers and investors alike:

PAGE 6

CHAPTER 1.

INTRODUCTION

Benefits to Governments and Taxpayers:

>

Allows governments to leverage their credit rating to monetize their existing assets,

freeing up capital to pay down previous obligations or fund ongoing programs;

>

Governments maintain ownership of structures that they have already financed;

>

Governments can continue to control and maintain facilities that are often critical to their

identity and function;

Benefits to Investors:

>

It represents a relatively safe long-term investment in a credit tenant;

>

Tax Exempt Status is granted at the federal level and at many state levels, on interest

earned from these investments.

>

It provides an outlet for pent-up investment capital from pension and mutual funds, life

insurance companies and private individuals;

> The lease onligations of many state and municipal governments are rated by Moody's,

Fitch's and Standard & Poors, providing an objective measure of risk to investors. In

many cases investors can obtain a yield premium above the government's GO rating for

essentially the same risk;

>

There is an opportunity for securitization and arbitrage of these investments by

originators and syndicators.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

Statutory conditions, including laws regarding municipal lease structures and annual appropriations, vary

from state to state, making generalizations and universal methodologies difficult. However, the rationale

and models investigated here can be adapted for application to many states and municipalities throughout

the country.

The analysis in this thesis focuses on the State of California, as it currently has one of the most significant

budget crises in the country. In addition, California has the largest state-owned real estate portfolio, and a

20 year history of lease-backed and structured financings.

PAGE 7

CHAPTER 11.

CHAPTER II.

II.

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

OVERVIEW

As mentioned above and described in detail in Section V., the State of California currently owns over 102

Million square feet of real estate in more than 16,000 individual facilities. When including properties in

the State university systems, this portfolio measures over 192 Million Square Feet in over 22,000

facilities. The development or purchase of many of these assets was financed directly with taxpayer

dollars from State's General Fund or through State-Issued General Obligation (GO) bonds.

In more recent cases, municipal lease obligation bonds have been issued to finance the development of

State facilities, or provide a security interest to Landlords leasing space to various State agencies.

Depending upon factors such as structure and timing of the bond issuance and the State's corresponding

credit rating, the annual interest costs to taxpayers for these bonds is substantial.

DOES THE PORTFOLIO FIT THE MISSION?

What is the mission of the State Government? Is it to develop, invest or own and operate real estate?

Many argue that, overwhelmingly, the answer is no. The general role of government is to provide support

and services to promote and protect the security, health and well being of its constituents.

Typical

services include:

>

Fire Protection

>

Educational Services

>

Health Services

> Utility Services

>

>

>

Communication Services

Transportation Facilities and Services

Security (Police, National, and Civil Defense)

In some cases, such as civil or national defense, utilities or telecommunication, the ownership and control

of certain facilities is considered necessary or critical to the government's mission. However, in many

cases, the government's ownership of the physical facilities is not required in order for them to effectively

provide resources or services to constituents.

PAGE 8

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

CHAPTER 11.

As treasurers and CFO's of corporations, non-profits and NGO's alike have realized, ownership of real

estate does not increase their ability to generate value for shareholders or enhance their ability to carry out

their various missions. Recent market conditions and evolving transaction structures have allowed these

organizations to carry out sale-leaseback and even synthetic lease transactions that have enabled them to

re-deploy capital for mission critical uses, while maintaining occupancy and control of preferred facilities.

These models can be applied to state and municipal governments as well.

ADVANTAGES OF STATE OWNERSHIP

From the perspective of corporations, state and municipal governments alike, one of the most significant

advantages of real estate ownership is control. Historically, corporations and governments have desired

to control the design and development of key facilities, such as headquarters, capitals and other landmark

buildings that contribute to their identity and place in business or society. Additionally, having autonomy

over configuration, maintenance and capital upgrades at their facilities enable these institutions to amend

their operations and the use of their space to meet evolving needs or changes to their mission.

However, there are a variety of lease structures available to corporate and government tenants that can

provide them with a high degree of control over their facilities. As will be discussed in Chapter IV, Bond

Lease or Triple Net (NNN) leases to a single tenant can be structured to provide the tenant with complete

autonomy and control over the property.

In exchange for such autonomy, tenants must also take

substantial responsibility for property management and capital repairs, and for all costs associated with

operating the property.

In terms of enhancing or preserving the institution's identity, building naming or signage rights can often

easily be negotiated for tenants who are sole or majority occupiers of the building.

DISADVANTAGES OF STATE OWNERSHIP

There are several disadvantages to the ownership of real property that are specific to state or municipal

governments versus private individuals or corporations:

>

No Appreciation - Unlike private or corporate-owned, state owned real estate is primarily a

cost rather than an investment. Since States are rarely sellers of properties, taxpayers do not

receive the benefit of appreciation of these properties, essentially hindering the taxpayer's

return on these financed assets.

PAGE 9

1-1_1__1_-__,_'.__

11

1-

I --

-

"itlj"j"

CHAPTER 1I.

CHAPTER II.

-

-

-

- -

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

Increased OperatingExpenses - States are often required to hire more expensive union labor

for landscape, operation and maintenance of its facilities. Therefore, taxpayers tend to carry a

higher operating expense load than do owners and investors in privately held and operated

facilities.

>

Asset Management - States with large real estate portfolios must carry substantial overhead

associated with managing, maintaining and making improvements to their assets. Rarely

does this ongoing expense translate into better facilities and services for the state's

constituents.

>

Non-Optimal Use of Capital- When States own and operate substantial real estate portfolios,

the taxpayers have made and investment in fixed depreciating assets versus, mission critical

programs and operations. The credit worthiness (bond rating) of these institutions is better

leveraged to fund programs that achieve their mission rather than to build or own real estate.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS - SELL VS. HOLD VS. LEASE

Today, government administrators face a diverse array of budgetary and operating challenges. Budgets

and resources are reduced, and funding the immediate and long-term needs of the constituency has

become more difficult. As states review their real estate portfolios and analyze methods to monetize their

assets, they must weigh the advantages of ownership, disposal or leaseback on an asset-by-asset basis:

Asset Attractiveness

The attractiveness of different assets to different investors must be considered when conducting a sellhold-lease analysis. For example, a well-located and well-constructed office property may attract a

variety of investors who will place a premium the asset's quality and location. This may provide an

opportunity to for the state to obtain increased proceeds through a sale to investors who foresee asset

appreciation, with relatively little asset or leasing risk. Selling and leasing back in such a scenario allows

the state to obtain high proceeds while securing long-term use of a key facility.

On the other hand, an office property that is not as well located or constructed will likely attract only

those who wish to invest in the credit of the State. They will pay for the income over the lease term but

are not interested in taking on any asset or leasing risk at the end of the lease obligation. In this case, a

PAGE 10

, ,

-1 -1-

I

-

_-

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

CHAPTER 11.

Master Lease & Leaseback may be the best opportunity to leverage the state's credit, while retaining any

benefits of future property ownership.

Useful Life

The age of a given asset is another key consideration in the analysis. An older property, which may be

approaching the end of its useful life will be less likely to attract purchase investors, or will be discounted

because of its age, reducing the potential proceeds from a sale.

In the case of an older property, the only opportunity for monetization may be through a lase structure,

where the investor is paying solely for the credit of the tenant over the term of the lease. However,

proceeds available through this alternative may be limited, as investors will only agree to a lease term that

does not exceed the expected useful life of the property. In many cases, the best option for the state is to

continue to own and operate an older facility at the lower basis, as long as operating and improvement

costs do not become prohibitive.

Market Conditions

Market conditions including prevailing rents and vacancy rates are a key factor in the analysis that the

State must undertake. In a market characterized by high rents, the State may be better off either selling

the asset, or continue to own it using traditional mortgage financing or even General Obligation (GO)

bond financing, without bearing the additional costs of high lease payments. However, in a low rent

environment, it may be advantageous for the state to enter a long-term lease, and secure the long-term use

of key facilities at the lower rates, while using the proceeds to fund other facilities or programs.

Table 3.

Matrix of State Sell/Hold/Lease Considerations

Sell

Well Built &

Located

X

X

Newly Built

Aging

Asset

High Rents

Low Rents

X

X

X

Master Lease

Hold/Own

Less

Competitive

Market Conditions

Asset Age

Asset Characteristics

Monetizing

Strategy

X

X

X

X

PAGE I I

CHAPTER IL.

STATE OWNED REAL ESTATE

Strategic Implications

In addition to the above-mentioned quantitative or monetary considerations, states must weigh more

strategic implications when reviewing their real estate strategies. In many cases, states may desire the

ownership of key facilities such as capital buildings or legislative offices, as symbols of their identity and

sovereignty. Security, defense or critical communication and infrastructure nodes may also require the

strict control and autonomy that comes with ownership. They may also wish to control property in a

given neighborhood in order to preserve their option to expand.

PAGE 12

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

CHAPTER 1II.

THE CORPORATE SALE

CHAPTER III.

-

LEASEBACK MODEL

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

III.

OVERVIEW

Corporate ownership of real estate has been popular in the United States for much of the past century, and

many U.S. companies still maintain real estate portfolios.

However, as many treasurers and CFO's

throughout the world have realized, ownership of real estate does not necessarily increase their ability to

generate value for shareholders. Recent market conditions and evolving transaction structures have

allowed corporations to carry out sale-leasebacks that have enabled them to re-deploy capital for mission

critical uses, while maintaining long-term occupancy and control of preferred facilities.

In a typical sale-leaseback transaction, a property owner sells real estate used in its business to an

unrelated private investor or to an institutional investor. Simultaneously with the sale, the property is

leased back to the seller for a mutually agreed-upon time period. Leases are usually longer-term in

nature, and can run anywhere from 5 to 20 years, with the average lease term being 10 to 15 years, with

renewal options

3.

A schematic of a typical sale-leaseback transaction is provided in Figure 2.

Key components of a Sale-Leaseback transaction include:

>

The property involved in a sale-leaseback may include either or both the land and the

improvements.

>

Lease payments typically are fixed to provide for amortization of the purchase price over

the term of the lease, plus a specified return rate on the buyer's investment.

>0

The typical transaction usually involves a triple-net-lease (NNN) arrangement.

>

Sale-leasebacks often include an option for the seller to renew its lease, and on occasion,

re-purchase the property.

Key accounting and tax rules are applied differently to states then they are to corporations, and specific

legislative or statutory restrictions can impact the applicability of the Corporate Sale-Leaseback model to

an individual State or municipal government. In particular, it may require a vote or specific legislative

authority for a State to actually sell a given property. However, several advantages and disadvantages to

this structure do transfer to the Master Lease - Leaseback model, and are discussed here.

3 Barthell, 2001.

PAGE 13

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER III.

Figure 2.

Schematic of Typical Sale-Leaseback Transaction

Fee Interest in Land & Improvements

vest

TOO

~

nLegal

Corporation

Sale Transaction Costs:

Brokerage Fees

Fees

Title & Escrow Costs

Long Term Lease in Improvements

Investor Benefits:

* Large Transaction/Investment

* Long-Term Credit Income;

* Asset Appreciation;

* Depreciation Deduction.

Lease Transaction Costs:

Legal Fees

Recording Fees

Corporate Benefits:

* Cash Proceeds;

* Better Balance Sheet Accounting;

* Long-Term Lease Lock;

* Control and Occupancy of Preferred Location;

* Deductability of Rent Payments

Investor Risks:

*

Lesee Default or Bankruptcy

* Fire/Hazard Risk

Corporate Risks:

* Buyer Bankruptcy;

* Loss of Inflation Hedge;

* Market Rent Risk.

PAGE 14

..........

CHAPTER 1II.

CHAPTER III.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE CORPORATE SALE

-

LEASEBACK MODEL

SELLER BENEFITS:

Free Up Capital- Sale-leaseback financing can enhance a company's financial performance by freeing up

credit facilities needed for accounts receivable, inventory, growth, and expansion. It also indicates to the

investment community the company's commitment to transform previously under-performing assets into

cash for growth or other sound business reasons.

The same can be said for freeing up capital in government-owned assets. Master lease proceeds can be

used to fund or pay down GO bond obligations, or increase value to taxpayers by funding ongoing

government service programs.

Avoidance of Debt Restrictions - Businesses restricted from incurring additional debt by prior loan or

bond agreements may be able to circumvent these limits by using a sale-leaseback. Rent payments under

a sale-leaseback usually are not considered indebtedness for such purposes, thus a business can meet its

cash needs through the sale-leaseback without violating any previous agreements

4.

Similarly state governments that have approached their bonding limits, who do not want to impact their

credit ratings, or bear the expense of further bond commitments can use these transactions to generate

proceeds. In the case of California, GO bond issuance is subject to a super majority vote (2/3) of the

electorate, and there are substantial administrative and time requirements to carry out Bond financings.

Municipal leases and the issuance of associated Certificates of Participation (COPs) do not face the same

regulatory or bureaucratic hurdles.

Maintain Asset Control - As a single tenant signing a Bond or NNN lease, corporations are granted

substantial control and effectively, possession of their facilities throughout the term of the lease. Under

the Master Lease structure, the State continues to hold title to the property throughout the term of the

lease, and reclaims all rights and opportunities of ownership at the end.

Renewal Opportunity -A sale-leaseback also usually provides the corporate seller with renewal options at

the end of the lease term, while conventional mortgage financing provides no guarantee for refinancing.

In the case of a state Master Lease, states are unlikely to recommit to a lease without receipt of additional

proceeds. This would require re-evaluation of the facility and the credit of the State, and a renegotiation

of the lease and proceeds paid to the seller.

4

Barthell, 2001.

PAGE 15

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

CHAPTER III.

Leveraging Credit - In a typical purchase transaction, investors may only be able to leverage 70% to 80%

of a given assets income (credit) value at lower debt-like rates. However, in a longer-term leaseback

transaction, the investor is taking little or no asset risk, and the cost of nearly all of the investment capital

will be based on the tenant's credit rating. This will have the effect of reducing the rent that must be paid

by the tenant, and/or increasing the proceeds paid for the ownership interest.

Advantageous Market Conditions - As a result of the recent economic recession, which has been

particularly acute in California, office and industrial vacancy rates are at recent historic highs throughout

the State:

Figure 3.

Historic Office Vacancies in Major CA Markets

25.0

23.0

21.0

19.0

17.0

_

S15.0

S13.0

>.

11.0-

9.07.0

5.0

Q2/01

-+-

Q3/01

Q4/01

Q1/02

Q2/02

Q3/02

Los Angeles -

Sacramento -0-

Q4/02

Q1/03

Q2/03

San Francisco

Source: Grubb & Ellis Company, July 2003.

Figure 4.

Historic Industrial Vacancies in Major CA Markets

20.0

18.0

14.0 -

1600

12.0

-

10.0 8.0 4.0 2.0

~:-u

0.0

Q1/01 Q2/01 Q3/01 Q4/01 Q1/02 Q2/02 Q3/02 Q4/02 Q1/03 Q2/03

-4- Sacramento ---

Los Angeles -k

Silicon Valley

Source: Grubb & Ellis Company, July 2003.

PAGE 16

CHAPTER

111.

CHAPTER III.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

As a result of the glut of vacant space in the San Francisco and Sacramento office markets , and in the

Sacramento and Silicon Valley industrial markets, market rents in these locations have correspondingly

reached recent historic lows. Entering into long-term leases at this point in the market cycle allows sellers

or master lessors who wish to become tenants, to negotiate from a point of strength and effectively 'lock

in' valuable properties at lower rates.

Obviously, lower rent levels will reduce the proceeds that credit investors will pay for the lease interest.

However, treasury rates, and corresponding discount rates are also at historic lows (Figure 1.).

Since

discount rates are stronger levers of present value than incremental changes in income, the effect of lower

rents should be offset, and substantial capital can be released through these transactions.

Lower TransactionalCosts - In a Sale-Leaseback, the seller can often structure the initial lease term for a

period that meets its needs without the burden of balloon payments, call provisions, refinancing, or the

other issues of conventional financing. Moreover, the seller avoids the substantial costs of conventional

financing such as points, appraisal fees, and some legal fees '.

Improved Balance Sheet and Credit Standing - In a sale-leaseback, the seller replaces a fixed asset (the

real estate) with a current asset (the cash proceeds from the sale). If the lease is classified as an operating

lease, the seller's rent obligation is usually disclosed in a footnote to the balance sheet rather than as a

liability. This results in an increase in the seller's ratio of current assets to current liabilities, which

translates to a better ability to service short-term debt obligations

6.

SELLER DISADVANTAGES

Loss of Flexibility - The seller as the new lessee loses the flexibility associated with property ownership,

such as changing or discontinuing the use of the property or substantially modifying a building. The saleleaseback often restricts the seller's right to transfer its lease interest. Generally it is more difficult to

dispose of a leasehold interest than a fee-ownership interest.

In the Master Lease model, the State retains title over the property, throughout and after the lease term.

As long as the rentable square footage or income generated from the lease is not impacted, the State can

maintain authority and control over configuration and improvements.

5 Valachi, 1999.

6

ibid.

PAGE 17

CHAPTER

111.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

Risk of Buyer Bankruptcy - If the buyer in a Sale-Leaseback files for bankruptcy, the bankruptcy trustee

may reject any agreement to renew the leaseback or the seller's option to purchase the property. This is

not a risk in the Master Lease structure, because the Master Lease interest holder is a bankruptcy-remote,

single purpose entity or trust, whose sole reason for existence is to receive and redistribute income from

the Master Lease.

Higher Cost ofFinancing- The interest rate in a sale-leaseback arrangement generally is higher than what

the owner would pay through conventional mortgage financing. The same hold true for a municipal Sale

or Master Lease - Leaseback. As discusses in Chapter V the rating given to a State's lease obligations is

generally H step below that of its General Obligations (GO) bonds.

TransactionalCosts - The cost of negotiating a Sale-Leaseback may be higher, because substantial time

and effort may be required to tailor the transaction to meet the seller's needs. In a Master Lease

arrangement, there is no transfer of title or time required for escrow and closing formalities. As a result

these transactions are often speedier and less costly

BUYER ADVANTAGES

Higher Return Rate - The investor can receive a higher rate of return in a sale-leaseback than in a

conventional loan arrangement. In addition, at the end of the lease term, the buyer receives the benefit of

any appreciation in the value of the property. Finally, the buyer can leverage the purchase with mortgage

financing; this may further magnify the return rate on the cash invested.

In the case of a state master lease transaction, the investor will likely receive a premium over the state's

corresponding GO interest rate, for essentially the same risk.

Predictableand Secure Return Rate - The long-term net lease enables the buyer to estimate accurately the

expected future rate of return. Also, the extended term of the lease provides the buyer with protection

from downturns in the real estate market and an inflation hedge, assuming that the property value

appreciates over time.

In the case of a master lease, this advantage is lost, because ownership and any asset appreciation remains

with the State. Therefore, investors will have to consider interest rate risk as part of their analysis and

valuation.

PAGE 18

CHAPTER

111.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

GreaterEase in Handling a Seller Default - In the event that the seller defaults under the lease in a SaleLeaseback, the buyer can simply terminate the lease and have the seller evicted. The buyer bears the risk

of finding another tenant after the eviction process is completed.

As discussed in Chapter V., this is not so straightforward in a master lease - leaseback, when the tenant is

the owner. A different form of security interest is required for the seller to mitigate the state's default,

which is usually caused by a non-appropriation of lease funds.

Ownership of the Reversion - The buyer owns the reversionary interest in the property. If the seller has an

option to purchase or an option to renew the lease, this may limit or postpone the time that the buyer

actually realizes the profit potential. The buyer also bears the risk that the property value actually might

decline over the lease term.

In the case of a Master Lease, the buyer does not receive the benefit of a reversion or any associated

property appreciation.

BUYER DISADVANTAGES

Possibilityof Seller Default - Perhaps the biggest risk that the buyer faces in a Sale-Leaseback is that the

seller will default on the lease, which would leave the buyer without a tenant. If the seller files for

bankruptcy, the buyer is considered a general creditor. If the arrangement were a conventional mortgage,

the buyer would be considered a secured creditor. If the seller files bankruptcy in a soft real estate market,

the buyer may have a difficult time finding a new tenant.

In a state Master Lease and Leaseback, the risks are non-appropriation, or the Bankruptcy of the State.

The municipal markets and key rating agencies closely monitor the fiscal health of state governments.

Although possible, the risk of state bankruptcy is very remote.

The more imminent risk to a state

leaseholder is non-appropriations risk, and as discussed in Chapter V, this risk varies from state to state.

In the case of California, State lease-backed obligations are backed by the full faith and credit of the state.

Similar to traditional GO Bond financing, holders of the bonds are considered secured creditors in the

event of Bankruptcy and do not typically face annual appropriations risk.

Higher Administrative Costs - Because the typical sale-leaseback usually must be structured to meet the

specific needs and requirements of both parties, it may require more time and increased administrative

costs than a conventional loan transaction.

PAGE 19

CHAPTER 1II.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

RequiredPropertyManagement - In most cases, the seller assumes the responsibility and expense of dayto-day property management during the lease term. However, the buyer must make sure that the seller

pays the property taxes on time and that tax assessments are reviewed and challenged when appropriate.

The buyer also must periodically review the insurance coverage on the property and inspect it for proper

maintenance.

State and municipal properties are exempt from paying property taxes, so this obligation and

administrative concern is removed from the purchaser of the Master Lease holder. In addition, the

condition of the property throughout, and at the end of the lease term is not typically a liability of the

Master Lease holder.

FinancialAccounting Implications - Sale-leaseback accounting has its own GAAP authority.

For the

asset to be considered off-balance-sheet, the leaseback must be an operating lease, versus a capital lease.

If the lease is classified as a capital lease, which means that the transaction is essentially a purchase by the

lessee, the advantages of the sale-leaseback arrangement from an accounting perspective are altered

considerably. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 13 on accounting for leases requires that

a capital lease be recorded as an asset and capitalized and requires the obligation to make future lease

payments to be shown as a liability.

Four key restrictions of FASB 13 determine operating versus capital lease designation:

>

PV of rental payments (including termination or non-renewal penalties) must be less than 90% of

market value of property;

>

Primary lease term must be less than 75% of remaining useful life of property;

>

The Lease cannot transfer ownership to lessee during term;

>

The Lease cannot contain option to purchase option to purchase at discount.

MASTER LEASE VERSUS SALE

For economic purposes a properly structured master lease interest is nearly equivalent to a fee-simple

ownership interest. By providing a master lease interest rather than a fee-simple interest to an investor, a

given state or municipality can effectively go around legislative or statutory restrictions that would

prohibit it from conducting a sale, while reaping much of the economic benefit. Other reasons that a

master lease structure is more advantageous than an actual sale include:

PAGE 20

CHAPTER

111.

CHAPTER III.

THE CORPORATE SALE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE CORPORATE SALE

-

LEASEBACK MODEL

Lower Transactional Costs - Sellers of real property must pay brokerage commissions and legal fees, as

well as their share of title, escrow and transfer taxes involved in the transaction, which can approach 3%

to 5% of the sale value and reduce the amount of the proceeds actually received.

Asset Quality - Typically, government owned properties are not of Class-A quality, and are often in less

advantageous locations than competitive, privately owned properties, and investors will be investing more

in the credit of the tenant than in the physical attributes of the real estate. A master Lease and leaseback

will allow the government to maximize its credit value over the term of the lease, as it is unlikely that a

discount will be applied for asset quality or risk.

PAGE 21

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER IV.

IV.

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

Economically, a Master Lease - Leaseback transaction is very similar to a Sale - Leaseback. However,

structurally and contractually there are differences and characteristics specific to a Master Lease format

that are advantageous for both government entities and investors alike. A schematic of the structure of

this transaction is provided at the end of this chapter in Figure 5., and a discussion of its key components

follows below.

THE MASTER LEASEHOLD INTEREST

The Entity

In a Master Lease of a government facility, a single-purpose, bankruptcy-remote entity must be formed to

hold the interest, collect and distribute income from the lease. The entity is typically a trust that is formed

at Lease inception and dissolves at the conclusion of the term. This is necessary in order to prevent the

leasehold interest, escrowed reserves other economic interests of the state from being claimed and

transferred to another party through bankruptcy proceeds.

Structure

A typical master lease interest is an economic interest in the operations and income generated from the

property. The interest is usually limited to the built improvements, and does not include the land. Title to

the land and improvements of the property remains with the State, and the Master Leaseholder does not

participate in any appreciation of the asset.

Regulations vary from state to state regarding whether property taxes are payable on a leasehold interest

in real property. However, in most states, state and municipalities are precluded from paying property

taxes, and in structures where the state remains as the fee owner and title holder of the property, there is

not a requirement for payment of property taxes.

Term

The term of the Master Lease typically runs concurrent with the associated sub-lease back to the state

agency. This prevents exposure of the trust and its assignees to leasing risk or operating liabilities beyond

the term of the agreement.

PAGE 22

CHAPTER IV.

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

Insurance

The master lessee requires certain insurances to be in place to protect its economic interest in the asset.

This includes protection from fire, hazard, and in the case of California, earthquakes. Since the State

continues to be the sole occupier and operator of the property under the corresponding sublease

agreement, they will typically carry these insurance policies and will indemnify the master leaseholder

from any claims arising from loss or injury from such occurrences.

Assignment Rights

The Master Lease interest is held in a specially formed trust and is typically not assignable to other

parties. As discussed later in Chapter VI, the trust may syndicate and issue Certificates of Participation

(COP) to allow other investors participate in the lease income.

THE GOVERNMENT LEASEBACK

Although the Master Lease provides for the long-term 'ownership' rights of the investor, the terms and

structure of the accompanying Leaseback or Sublease agreement, with the State agency as the tenant, is

the key component that determines the value and security of the Master Leasehold investment.

Leaseback Type

There are three basic sublease structures that can be used in these transactions. A brief description of

each of the three follows:

Bond Lease - In a bond lease, the tenant (State) is wholly responsible for all aspects of the property and its

operation throughout the lease term, including liability for casualty and/or condemnation events. All base

rent is payable by tenant without any right of abatement or offset under any circumstance. The tenant

typically indemnifies the landlord, or in this case, the Master Lease holder against all liabilities arising

from its use or occupancy of the property. The tenant's only right to terminate the lease is based upon a

condemnation, in which case tenant must purchase the Master Lease interest in the property for at least

the un-amortized balance of its sublease payments.

Triple Net (NNN) Lease - This lease is very similar to a bond lease, except the tenant has the right to

terminate the lease or abate rent due to an event of casualty to or condemnation of a portion or all of the

PAGE 23

CHAPTER IV.

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

property. Lease enhancement policies, arranged at the borrower's expense, are required in such instances

to insure over the risk of rent abatement or lease termination.

Double Net (NN) Lease - This lease mimics a NNN lease, except the lessor will have certain ongoing

obligations with respect to the property. The failure to perform the obligations could result in the tenant

(State) having the right to abate rent or terminate the lease. Typically, such obligations include

maintenance, repair and replacement obligations for roof, structure and parking. Additional debt service

coverage and maintenance and repair reserves are required in such instances. Additionally, lease

enhancement policies are required to insure over the casualty and/or condemnation risk.

For the purposes of the model presented here, and in most leaseback transactions that have occurred in

California, the preferred arrangement is a NNN lease. This provides the State with complete freedom of

use for the property, and requires it to assume all real estate risks and obligations of ownership. However,

since the State is not issuing a separate bond to guarantee payment of the lease, it is generally provided a

rent abatement in the event of casualty or condemnation

Term of Leaseback

Key considerations in determining the appropriate length of the leaseback of the facility to a State agency

include the age and condition of the property and historic tenancy of the property, as well as the mission,

solvency and perceived longevity of the occupying agency. Investors must review the history of the

facility, as well as the importance and historic funding of the occupying agency (tenant), and commit to a

lease term which is appropriate to these conditions. In no case should the lease extend beyond the useable

life of the property. Typically, lease terms average 10 to 15 years

Security Interest

The biggest risk to investors in government leases is non-payment of lease rent resulting from nonappropriation. Typically, states and municipal governments may enter into long-term leases for facilities,

but the availability of funds to pay the lease rents is subject to approval in the agency's annual operating

budgets.

A holdback of investment proceeds is one method that is commonly employed to provide

greater security from appropriation risks

Proceeds Holdback - A reserve or holdback of a portion of the proceeds payable to the state for the lease

is held in reserve as a security against default or non-appropriation. Typically, a reserve amounts to a

7

Valachi, 1999.

PAGE 24

CHAPTER IV.

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

percentage of the total proceeds that is enough to cover at least one years worth of rental payments from

the state. This is usually held in an interest bearing escrow, with the interest either being credited against

the rent due each year, or accruing for the benefit of the state and released at the end of the term.

Sublease and Assignment Rights

Over a 10 to 20 year period, state agencies may alter the way that they utilize their space. Granting the

state or agency the right to sublease a portion or all of the space is not an issue, as long as the state

maintains responsibility for the lease payments. Assignment rights are usually not as easily granted, and

are typically only allowed in the case of one state agency assigning its lease to another.

Insurance

The lessee should agree to maintain the leased property in good repair and to insure it against loss or

damage in an amount at least equal to the lease value. If lease payments are subject to abatement in the

event the property is damaged, destroyed, or taken under a provision of eminent domain, the lessee must

typically maintain business interruption insurance.

VALUATION AND PROCEEDS

Proceeds paid for the lease are derived using a typical present valuation methodology. The schedule of

net lease income is discounted back over the term of the lease at a rate commensurate with the State's

credit rating, plus a premium for any perceived appropriation or asset risks. Effectively, the discount rate

applied equates to interest paid for borrowing against the State's future revenues.

In some states, lease investments do not have the same "full faith and credit" backing as municipal

General Obligation bonds. As described in Chapter V., these investments are rated at least one notch

lower than a state's GO rating by rating agencies, and a risk premium is added to the discount rate. This

results in more expensive 'borrowing' by the state. In California, where lease obligations are backed by

the 'full faith and credit' of the State, they are generally rated % notch below the state's GO Bond rating,

resulting in a less significant discount.

PAGE 25

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

THE MASTER LEASE - LEASEBACK MODEL

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER IV.

Figure 5.

Schematic of Master Lease-Leaseback Transaction

Master Lease Interest in Improvements

State Government

Lease Transaction Costs:

Legal & Recording Fees

Underwriting Fees

Long Term Sub Lease in Improvements

h-Yield Fixed Income Invest

Mutual Funds

Private Investors

Lease Transaction Costs:

Legal & Recording Fees

Insurance Fees

Government Benefits:

* Cash Proceeds;

* Long Term Lease Rate;

* Control and Occupancy of Preferred Location;

Undrrtr

Investor Benefits:

* Long-Term Credit Income;

* Opportunity to Syndicate & Arbitrage

Investor Risks:

* Non-Appropriation

* Fire/Hazard Risk

Government Risks:

* Loss of Inflation Hedge;

* Market Rent Risk.

PAGE 26

MI

11111OWM,

- - - , IOW I i

W

, 111-,--_-_ -1 -1 __ -,

,"

"

-,- , -

-

.

-

.

0,

oil

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER V.

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

V.

A key component to valuing the income stream from the lease investment and determining the proceeds

that will be paid to the State in the transaction is the rating that the State's leaseback obligation is given

by agencies such as Fitch Ratings, Moody's Investor Services and Standard & Poor's (S&P).

These

rating agencies have developed a thorough set of criteria for rating municipal leases and associated

investment certificates.

CATEGORIZATION OF LEASES

The ratings these agencies apply to lease-backed securities can vary widely, depending on the credit

strength of the tenant (State) and the structure and terms of the lease. Also, constitutional and statutory

laws regarding the structure of leases differ amongst the states. However for rating purposes, municipal

leases are categorized in one of two ways:

>

Leases resembling long-term debt, or

>

Higher-risk obligations requiring annual appropriations and having limited legal remedies.

Debt-Like Leases

Ratings for the first category reflect the long-term and binding nature of the lease. In cases where the

lease is long term, and the legal recourse to leaseholders is similar to that of a long-term debt holder,

ratings may be as high as the State's senior General Obligation (GO) debt rating.

In the case of

California, existing lease-purchase revenue bonds are generally backed by the 'full faith and credit' of the

state, and are funded out of the appropriate State agency's operating budget. As a result, their credit

rating is generally half a step below the GO bond rating.

Leases with Appropriations Risk

The second category involves leases that depend on budgetary appropriations by the State, and legal

remedies are limited in the event of non-appropriation. Because of the risk that lease payments may be

terminated before the end of the term, ratings on these transactions would be lower than the State's full

faith and credit rating. Typically, the lease rating is one full category below 8.

' Standard & Poor's, 2000.

PAGE 27

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

CHAPTER V.

To rate a lease transaction requiring annual appropriations, Standard & Poor's evaluates the following:

> General creditworthiness of the State;

>

Essentiality of the leased property;

>

Security features in the lease agreement.

STATE CREDITWORTHINESS

As a tenant, a state's general creditworthiness is reviewed in the same way as it's Credit Rating, or as if it

were issuing General Obligation (GO) bonds. The State of California has historically maintained what is

considered a high 'investment grade' credit rating. Investment Grade ratings are those that are rated A or

above by the key rating agencies. The table below provides a summary of California's current credit

rating by the various rating agencies.

Table 4.

State of California Credit Rating

Rating Agency

Fitch Ratings

GO Bonds as of July 31, 2003

Best Attainable Rating

CurrentRating

AAA

A

Moody's Investors Service

Standard & Poor's

A2

Aaa

BBB

AAA

Source: CA State Treasurers Office, July 28, 2003.

The above ratings are on General Obligation (GO) bonds, which are the highest quality debt instruments

issued by the State of California. The General Obligation (GO) bonds are backed by the full faith and

credit of the State of California. Ratings on these bonds are what people usually refer to when speaking

on the subject of a state or municipality's credit rating.

It is worth noting that all three agencies lowered their ratings on California's GO Bonds in late 2002 and

early 2003, citing the State's "inability to sufficiently address the 2003-04 fiscal year imbalance," and that

the anticipated level of deficit would likely exceed the State's level of other borrow-able funds 9. Lower

credit ratings not only hinder the State's ability to issue new bonds, but also increase the cost of doing so

substantially. To further exacerbate the problem, Standard & Poor's downgraded California's GO bond

rating three notches further to BBB during the week of July 2 1 ', 2003. This credit rating is just one step

above 'junk' status.

9Califoria State Treasurers Office, July 2003.

PAGE 28

.- 1-,&_1 -1-i---,,_ _

_-

-

-

I

ft ,

-

-1- -

-

CHAPTER V.

9 4

11 -_

-1

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

ESSENTIALITY OF THE FACILITY

The risk for non-appropriation is a key risk for the lessor/investor and, by assignment, any security or

certificate holder of the lease investment. As investors pursue the leaseback and securitization of Stateowned assets, it is necessary to understand these risks as they apply to individual assets.

Annual appropriation often depends on the importance of the leased property in providing essential

governmental services. Services generally considered to be most essential by agencies such as S&P

include police and fire protection, general government or courthouse facilities, or utility services. The

rating rationale follows the idea that funding for facilities and services considered important to the state's

operations are more likely to receive appropriations '0. While there is no precise formula to calculate a

facility's importance, agencies like Standard & Poor's ask the following questions when evaluating lease

issues:

>

Is the facility vital to the community, could the government function properly without it?

>

How does the facility tie into the government's total delivery system?

>

What would be the impact of not providing the facility or terminating the lease agreement

before the end of the lease term?

>

Would it be practical, either financially or within time restrictions, for the government to

accomplish its mission through or in another facility?

After determining a facility's importance to the State, the length of the lease term also figures into the

essentiality equation. In all cases, the lease obligation term should not exceed the estimated useful life of

the asset(s).

SECURITY FEATURES

The history of legislative authorizations for lease financings, prior leasing experience, and the intent of

the lessee are important in determining lease ratings. However, these factors are not substitutes for

adequate legal protections.

10Standard & Poor's, 2000.

PAGE 29

RATING THE LEASE INVESTMENT

CHAPTER V.

A lease contract's legal features, for the most part, must meet Standard & Poor's basic criteria to achieve

an investment grade rating. Their absence, or their deviation from the basic criteria in a significant way,

may adversely affect the rating

Appropriation and Term

The following lease appropriation features are viewed positively by Standard and Poors. Their absence or

significant variation may adversely affect the rating:

>

The useful life of the leased property or project matches or exceeds the term of the lease contract.

>

The term of the lease contract matches the term of the bond issue or certificates of participation,

avoiding exposure on renegotiation; if state law prohibits long-term leases,

>

The lease payments represent installments toward an equity buildup in the leased property. At the

end of the lease and, all outstanding principal and interest should be repaid to the investor,

allowing ownership of all interests in the property to revert to the lessee.

>

The lessee (State) agrees to request appropriations for lease payments in its annual budget.

>

For California lessees, the lessee covenants to appropriate lease payments, subject to abatement in

the event the leased property is not available for use. Although Standard & Poor's also rates

annual appropriation-style leases for California issuers, abatement leases are viewed favorably for

their accruing characteristics

12

Security interest.

Security interest is a common lease feature, in which the lessee grants the lessor - or the trustee collateral of security to protect the lessor in case of event of default or non-appropriation. In the case of

such an event, the lessor, or its assignee, has the right to some form of possession of the leased asset, or

receives refunds or deposit monies from its investment to compensate for its loss.

A lack of security interest does not automatically mean that the transaction cannot achieve an investment

grade rating. Rating agencies will evaluate the transaction within the context of the that state's laws and

the government's specific circumstances, but this feature should be included if it is available.

" Standard & Poor's, 2000.

12 ibid.

PAGE 30

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VI.

VI.

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

This section investigates the application of the Master Lease - Leaseback transaction model to an existing

State-owned office building in the Capital District of Sacramento, California. It will provide an example

of methodologies for deriving key lease terms as well as the resulting valuations and syndication

structures that are likely in the investment markets. An analysis of the benefits, drawbacks and fiscal

impacts to the State is also provided.

Urban office properties are typically given a high investment priority by institutions, as well as individual

investors, and provide a good case to apply the model presented here. Details regarding key physical

aspects of the asset, as well as operational and tenancy information are provided below:

Table 5.

CA State Office Property Details

Address:

Building Type:

Mid-rise Office, Class-A

Twenty

Stories:

Construction:

Year

450 N Street, Sacramento, CA

Built:

Net Rentable Area:

Current Tenant:

Length of Tenancy:

Use:

(20)

Concrete and Steel

1991

501,060 sq. ft.

California Board of Equalization

Twelve (12) Years

Headquarter Office

The office building at 450 N Street was funded and developed by the state's largest pension fund, the

California Public Employees Retirement System (CALPERS) in 1991. Located in the heart of the State

Capital District, the building was a build-to-suit for the State government.

Within a few years of

completion, the State issued GO bonds to purchased the property from CALPERS, and the State Board of

Equalization (BOE) has remained as the sole tenant.

PROPOSED LEASE TERMS

The structure and terms of the Sub-lease to the BOE drive the value to the investors and the capital

proceeds that will be made available to the State. A discussion of key terms of the proposed lease

agreement follows.

PAGE 31

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

CHAPTER VI.

Type of Lease and Term

Historic Tenancy - In considering the appropriate term of the lease, the history, mission and estimated

longevity of the particular State agency or agencies occupying the building should be weighed. In this

particular case, the State Board of Equalization (BOE) has been the sole tenant of the building since it

was first put into service in 1991.

DepartmentalMission - Established in 1879, the State Board of Equalization (BOE) is responsible for

administration and collection of over $41.24 billion (2002) in annual sales and use taxes, property taxes

and special taxes, as well as the State tax appellate program 13. 450 N Street has been the BOE's

headquarters since 1991. Because of the agency's critical role in revenue generation and administration

within the State government, its longevity is secured and it is anticipated that it will require full use of the

facilities at 450 N Street for a long time.

Useful Life - The property, which was constructed and put into service in 1991, is a modern, Class-A, 20story office building, built of concrete and steel, with a curtain wall facade. The State has maintained the

property well over the past 12 years, and has carried out series of capital improvements to its systems and

services. Based upon reports from engineers, architects and MEP contractors, the remaining useful life of

the building is estimated to be at least 25 years. Based on these considerations above, a 20-Year, NNN

Lease could easily be underwritten. However, for the sake of a simplistic example here, a 10-Year NNN

Lease is underwritten.

Lease Rent

In order to derive a fair and equitable lease rent, the parties should have an understanding of the current

economics associated with ownership and operation of the building, as well as comparable rents and

expenses in the local office markets. Key parameters are outlined in the table below:

Table 6.

Sacramento Capital District Office Rent Analysis

Rents and Expenses per Sq. Ft. per Month

Low

I

High

Range of Gross Rents

Average Operating Expenses

NNN Equivalent Rent

$2.20

$0.63

$1.57

$2.45

$0.63

$1.82

Annual NNN Rent

$18.84

$21.84

Source: Jim King, CB Richard Ellis, Sacramento

"3California BOE, July 2003.

PAGE 32

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

CHAPTER VI.

A SAMPLE

CHAPTER VI.

TRANSACTION

Comparable Market Rents - Currently, gross rents for office space in the Capitol District range from

$26.00 to $29.00 per sq. ft. per year.

Average expense loads on buildings of similar profile in the

Capital District, including property taxes, is $7.50 per sq. ft. per year. From this market information, we

can derive an equivalent NNN rent of $18.84 to $21.84 per sq. ft. In this sample transaction, a starting

NNN rent of $19.00 per sq. ft. per year will be used.

Rent Steps - Office and Industrial leases in California urban markets, especially longer-term leases, often

include rent steps. Typically, Northern California office leases include a CPI adjustment every fifth year.

For purposes of underwriting, CPI will be assumed to increase by 2.0% annually. Therefore, the rental

agreement will include a NNN base rent increase of 10% at the beginning of the 6th year, as follows:

Table 7.

Proposed BOE Rent Schedule

Year

1 " - 5 th

NNN Rent per Sq. Ft. per Year

$19.00

6 th -

0

th

$20.90

Property Management

Historically, the BOE has operated and maintained the facility, and under the terms of the proposed NNN

Lease, all costs and responsibilities for doing so will continue to be born by the State and BOE.

Security Interests

Covenant to AppropriateFunds- The State will covenant in the lease agreement to take such action as

may be necessary to include all rental payments due under the lease agreement as a separate line item in

its annual budgets and to make the necessary annual appropriations.

Security Reserve Fund - In addition to the State's covenant to appropriate for lease payments, a Security

Reserve Fund will be established to withhold in an escrow an amount equal to the lesser of (i) 10% of the

proceeds available from the investment, or (ii) 125% of the average amount of annual Base Rental

Payments. The Security Reserve will be held in an interest bearing escrow, and released to the investors

in the event of missed payments or default of the lease. As long as there is no default or other release of

the security reserve, annual interest that accrues will be used to offset the State's annual rent payments.

PAGE 33

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

VI.

VALUATION

A spreadsheet illustrating the underwriting and valuation of this proposed lease transaction is provided in

Table 9., at the end of this chapter. The first component of the underwriting is a projection of annual net

income stream. As illustrated in Section I. of the analysis, the investment produces annual net rent

payments of $95.2 Million in the first year, increasing to $104.7 Million in Year 6. Total net income to

the investor over the ten-year lease is projected to be $999.6 Million.

Credit Analysis and Bond Yields

The required market yield on this income stream is projected based on an analysis of yields for similar

municipal-backed fixed income securities. The following table provides an overview of market yields

associated with various Treasury securities and differently-rated municipal bonds:

Table 8.

Yields on Municipal Bonds and US Treasuries

UI.S.

MNticipal Genteral Obligationt B3onds

Mlaturity

lY

2Y

3Y

5Y

AAA

0.93

AA

0.96

A

1.19

BAA

1.55

Treasuiries

1.31

1.83

2.7

1.37

1.91

2.79

1.74

2.3

3.18

2.16

2.78

3.7

1.65

2.12

3.23

--

7Y

3.42

3.54

3.98

4.42

--

toy

3.95

4.07

4.46

4.92

4.37

15Y

20Y

30Y

4.48

4.82

4.95

4.6

4.93

5.07

4.95

5.17

5.3

5.41

5.6

5.7

---

5.27

As discussed previously in Chapter V., the State of California's GO Bond Rating is currently on the lower

end of the 'Investment Grade' ratings. Blending the current ratings of S&P, Moody's & Fitch described

in Chapter V., puts California GO bonds within the 'A' category above. However, as also discussed in

Chapter V., California's lease obligations are usually rated one to one-half grade below the State's GO

bond rating, putting it into the 'BAA' category above. Therefore an investor's expected yield in a 10Year lease to the State of California would be 4.92%, or 50 basis points above current 10-Year US

Treasury yields.

PAGE 34

CHAPTER VI.

A SAMPLE TRANSACTION

Market Investment Value

As illustrated in Section III of the analysis, application of this 4.92% discount rate to the ten-year income

stream from the lease results in a market investment value of approximately $770 Million. However, not