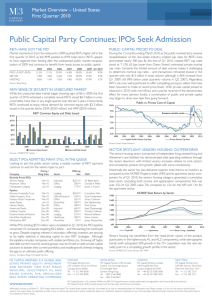

THEORY AND PRACTICE OF DEBT FINANCING IN...

advertisement