Near 14 Columbia of Juvenile Review: Bird Predation

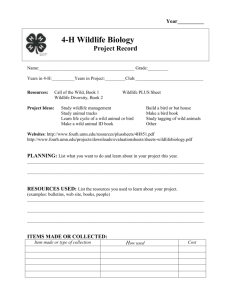

advertisement