The Process of Resort Second Home Development Demand Quantification:

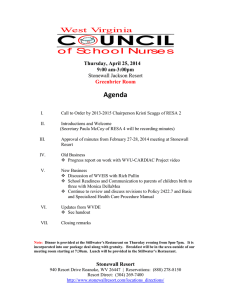

advertisement