The Effectiveness of Zoning in Solidifying Downtown Retail

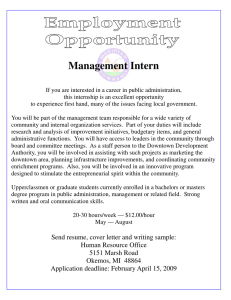

advertisement