Simulation Scenario Human Rights Accountability in Democratic Republic of Congo

advertisement

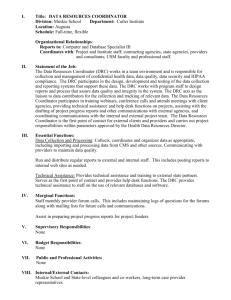

Simulation Scenario Human Rights Accountability in Democratic Republic of Congo This exercise is designed to illustrate the difficulty inherent in reaching agreement among multiple parties to provide accountability for human rights violations. In conflicts where there is no clear winner, it is not possible for one actor to simply dictate the legal framework for prosecution: instead, these parties must negotiate a framework that takes into account the priorities of all in order to reach an acceptable agreement. As a representative of a key actor, you must have a clear understanding of your own interests, awareness of others' preferences, and an understanding of what compromises will be acceptable to your constituents. There are three components to your participation: 1. Research preparation You have been given a role sheet with background information and starting points for further research. This information is confidential, and should not be shared with other teams. As you gather information be sure to keep the concerns of your constituents in mind, failure to honor these concerns could result in your being fired from your job – or worse! Your research will consist of identifying your party's positions on each of the issues to be negotiated, and determining your red and green lines on each issue. (red and green lines will be discussed during our preparation sessions) Finally, you will prepare a proposed agreement to present to all delegations as a group. 2. Proposal presentation Each group will present their proposed framework in a session with all delegations in attendance on Thursday. You will have 10 minutes to present your preferences. During this session, there will be no negotiation although questions may be asked. You should take notes on the competing proposals to discuss with your group that evening as you revise your position. 3. Final negotiation session On Friday morning, you will undertake negotiations with all parties present to arrive at a final agreement. Each issue will be discussed in turn, with time limits enforced. Be prepared to advocate for your position with the other parties. A final vote on the overall proposal will be taken, with each delegation having one vote. The vote must be unanimous for the framework to be passed. Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 Bear in mind that it may not be possible to reconcile the differences among these parties in this negotiation session. Although reaching an agreement is a priority, the higher priority is to represent and protect the interests of your group. Introduction It is the spring of 2016, and negotiations to end the twenty-year conflict in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are nearing a conclusion. After more than a year of tense, stop-andstart negotiations, the major parties have agreed to the shape of an agreement that addresses territorial disputes, resource distribution, and political transition. While there are still significant questions yet to be resolved on these points, there are mechanisms in place to restore rule of law and create a more inclusive governance structure in the country. These institutions are intended to allow legal resolution of remaining conflicts and ensure that all groups are represented in the new governing structures, allowing final resolution of these remaining questions to be completed over time. With most other issues now largely resolved, the delegations present must turn their attention to addressing the human rights violations that have occurred during the past two decades. This has proven to be the most difficult issue, and has therefore been deferred to the future each time it was discussed. Over the past two decades, DRC has experienced nearly constant conflict – ranging from low-level local disputes to full-scale foreign intervention and everything in between. It is critical that some mechanism be created that ensures accountability by those involved, both to ensure justice for the victims as well as to create a sense of closure on the past to allow for a new beginning. As participants, you represent key parties in the conflict and the peace process. In order to reach a successful conclusion to these talks, a framework for human rights accountability must be designed that is sufficiently strong to ensure justice and closure, yet still acceptable to all parties represented. Each party will need to identify the parameters of an acceptable agreement for their constituents and then negotiate with other teams to craft a single framework acceptable to all. Successful resolution will require clear understanding of your own positions and interests as well as effective communication and negotiation skills. Crisis in the Congo The current conflict is but the latest chapter in the difficult history of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The actors represented here represent the key parties in the conflict, although there are many more that have been involved throughout the previous decades. On review of the case, it is clear that no actor has acquitted itself well – each in its own way has contributed to the conflict and human rights violations that have occurred. It is therefore important to bear in mind that no single party bears sole responsibility for the conflict and only together can they bring this chapter to a close. A combination of political, territorial, resource, and ethnic factors have converged in DRC to produce multiple causes of the ongoing conflict; no Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 single cause alone can be singled out. What follows here is a very short overview of the history of DRC, with emphasis on the involvement of the actors present in this negotiation. During its time as a Belgian colony (then known as Belgian Congo) its people experienced some of the most brutal colonial treatment on the continent. The Belgians abused the people with forced labor and exploited the mineral wealth of the country while investing almost nothing in return, leaving a woefully underdeveloped and divided nation when they finally left in 1960. Caught in the Cold War between East and West, the newly independent nation of Republic of Congo experienced political turmoil, assassination, and eventually dictatorship driven in large part by the United States as it attempted to keep the Soviet Union from gaining a foothold in the region. Mobutu Sese Seko, ruled the country (then called Zaire) starting in 1965 with political, military, and economic support from the United States. During his reign, Mobutu stole billions of dollars from the national treasury while neglecting basic governance and infrastructure, causing observers to coin the phrase “kleptocracy” to refer to his governing style. This neglect was most pronounced in the eastern part of the country, where resources were taken by national and foreign companies with little returned in terms of development funding. The lack of state presence in the eastern provinces contributed to the rise of local leadership, often with ethnic identity as the primary basis for loyalty, and a deep hostility toward the national government in Kinshasa. With the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s U.S. support also ended, leaving Mobutu increasingly isolated and out of touch. An influx of refugees in the early 1990s due to civil wars in neighboring Rwanda and Burundi led to additional ethnic tensions and competition for resources in the eastern part of the country among Tutsi and Hutu groups despite international assistance through the UN and other NGOs. Adding to these factors is the presence of rich resources in the eastern part of the country including timber and a host of valuable minerals. In the early 1990s another factor began to influence conditions in DRC: the rise of technology. New appliances such as mobile phones, computers, video game systems, and other electronic devices rely on a metallic ore called coltan that yields the tantalum necessary to create ever-smaller circuits with high heat-resistance in these sophisticated devices. DRC holds the world’s largest known reserve of this material, and it is readily accessible without sophisticated mining equipment. Trade in this conflict mineral has driven fighting in many areas of DRC as groups derive funding from selling to international buyers who rarely ask about the legitimacy of the source of this valuable material. Multinational companies, as well as Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda, have been accused of trafficking in illegal coltan. In 1994, Rwanda was torn apart by 100 days of genocide that resulted in at least 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu allies killed by the government and affiliated “Hutu Power” extremist militias. At the end of the genocide, as rebel forces of Tutsi and moderate Hutus swept through the country, the genocidaires fled across the border into Zaire, where they found temporary refuge in UN refugee camps. These militias continued a campaign of genocide against Tutsi in Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 Zaire (known as the Banyamulenge) and continued cross-border attacks into western Rwanda. By 1996, the governments of Uganda and Rwanda joined with local rebels (funded and supported, in part, by the United States) to end the attacks and eventually depose Mobutu in 1997. The country was renamed Democratic Republic of Congo as Mobutu fled and LaurentDesire Kabila became President. This alliance broke down shortly afterward, when Kabila expelled Ugandan and Rwandan forces fearing that they may be preparing to remove him from office. Continued ethnic conflict and the refusal of Rwanda to leave bases around Goma in the east of the country led to massive intervention in DRC starting in 1998. Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Angola sided with DRC against Rwanda and Uganda, in fighting that lasted until the assassination of Laurent Kabila in 2001. His son, Joseph Kabila, became President and called for negotiations among all parties. This resulted in a peace that included withdrawal of foreign forces, power-sharing among political groups, democratic elections, and economic support for the transition. UN peacekeepers were deployed to facilitate the peace process and elections in 2006 that returned Kabila to power. The election results (with Kabila receiving over 70% of the vote) were deemed fraudulent by rebels, leading to a resumption of fighting in the east of the country. In 2009, DRC agreed to allow the Rwandan military to return to DRC to root out Hutu Power militias that were attacking DRC forces, threatening Rwandan border security and engaging in ethnic targeting of civilians. These militia groups utilized mass killing, rape, and property destruction to attempt to drive Tutsis and moderate Hutus out of the region. UN and African Union peacekeepers were unable to intervene to protect these civilians due to both mission limitations and lack of military capability, while DRC forces were under-equipped, undisciplined, and in many cases not paid for months at a time. Rwandan military units were able to arrest key leaders, turning them over to DRC for trial. The resulting peace deal allowed rebel forces to reintegrate into the DRC military and have representation in the government. Although low-level violence and clashes continued in the region, a period of relative calm was in place until 2012, when approximately 700 of these reintegrated troops left the military accusing DRC of fraud in the 2011 elections and failure to meet treaty obligations. The March 23rd Movement became the M23 rebellion, which rapidly moved to capture Goma, a city of 1 million people, over minimal resistance from DRC troops. Allegations of covert Ugandan and Rwandan support for M23 threatened once again to renew large-scale fighting in the region, leading to an incident of alleged shelling of Rwandan territory by DRC tanks and mortars in November, 2012. The surrender of alleged M23 leader Bosco Ntaganda to the U.S. Embassy in Rwanda severely weakened the rebellion, although some splinter groups continue to launch infrequent attacks. In February 2013, a peace agreement was signed by 11 nations (including DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda) designed to stop fighting and begin work on a new formal peace treaty for DRC. This agreement has produced multiple rounds of talks, of which this current meeting is the final step. Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 Counting the human cost of the past two decades of fighting is a challenging task, and one that remains controversial. Some human rights groups place the total at over 5 million dead, although their means of estimation are, at best, based on debatable assumptions. In particular, it is important to consider the low life expectancy in DRC, and especially the eastern part of the country given the centuries of neglect that it has experienced. More rigorous analyses that focus on only deaths beyond what would be expected in peacetime place the number at slightly less than 1 million. However, deaths are not the only statistic that is relevant here, and in fact are in many ways easier to comprehend and prosecute. There are many millions of individuals who have had their lives irrevocably altered by the fighting in DRC, who have been driven into refugee camps, been physically and sexually assaulted, and persecuted based on their ethnicity or proximity to resources. You should also review the latest news from the country, your assigned role, and the region as part of your preparation efforts. Issues There are three main issue areas to be decided in this conference, each one containing a number of options. All three issue areas must be decided for this agreement to be successfully concluded. It is up to each team to provide details under each section, including specific details of what categories are included in each option and any exceptions, inclusions, or additional parameters they wish to include. 1. Who is subject to prosecution? Direct violators – individuals who personally participated in violations Commanders – those who directly ordered, but did not take part in, violations Enablers – those who indirectly enabled violations through provision of supplies, funds, or other forms of support 2. Which acts will be covered by this agreement? Physical violations – including attacks on civilians, rape, property destruction Territorial violations – including unlawful intervention, support of militias Economic violations – trafficking in conflict minerals and other resources Ethnic targeting – special penalties for violations based on ethnicity Passive assistance – support for violations in indirect forms, including political and economic assistance or ignoring/declining to prevent violations 3. Venue for prosecution (for each above category) International tribunal – an ad-hoc judicial process based on UN norms Courts where crimes were committed – in most cases, DRC Courts of home countries – accused stand trial in their home countries Parties may also bring additional issues to the floor for consideration during these sessions. Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 Actors The following parties are represented in this conference. Each has varying degrees of involvement in the conflict and the human rights violations that have taken place, and each one is an essential piece of the peace process to end the fighting. Government of Democratic Republic of Congo The government of DRC is keenly interested in ending fighting within its territory and restoring stability in the eastern provinces. This agreement has to ensure not only peace and stability, but meet the demands of justice of DRC citizens who have suffered for so many years. The DRC has been accused of support for ethnic-based militias (including some groups implicated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda), failure to provide rule of law in the affected territories, and failure to prosecute human rights violations by its military. Government of Rwanda Rwanda shares a border with DRC and has long expressed concerns about border security resulting from the ongoing fighting. Any agreement must provide a stable peace and restore cooperation within the region. Rwanda is one of several countries accused of covertly sponsoring militia groups engaged in human rights violations, engaging in periodic cross-border military activities, and failing to prosecute accused violators within their own territory. Government of the United States The involvement of the U.S. in DRC is long and controversial, but its political, economic, and military resources are essential to a lasting peace in DRC and the larger region. U.S. interests are to ensure a lasting peace that stabilizes politics and markets, but without establishing new norms of accountability for violations. The U.S. has been accused of ignoring illegal profiting by domestic companies from resources plundered during the war, and of continued military support for parties engaged in the fighting in DRC. United Nations Peacebuilding Commission The UN has been engaged with humanitarian relief and peacekeeping efforts throughout the 20 years of the conflict, and has brokered the current peace deal. Any deal must fit within UN goals and norms established over decades of peace and reconciliation experience. UN personnel are accused of human rights violations including human trafficking, bribery, and covert support for parties involved in the conflict as well as refusing in many cases to dispatch peacekeepers on the ground to stop violations while they were taking place. Human Rights Watch Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013 HRW is representing the large number of non-governmental organization actors involved in DRC, and has at various times issued reports critical of all parties represented here. The agreement must not disrupt humanitarian assistance by endangering NGO workers. Many NGOs in DRC have been accused of supporting combatants with relief supplies (usually, although not always, unintentionally), involvement in human trafficking and other human rights violations, and of other forms of support for combatants. In addition, the final conference meeting will be moderated by representatives from the African Union. Although involved in the conflict as mediators and peacekeepers, the AU has recused itself from the negotiation process due to the large number of member states with interests in the outcome of the process. The AU has agreed to be bound by the outcome of these negotiations, and has committed to full support of the final agreement. Resources from the United Nations and the United States will be allocated through the African Union for capacitybuilding for the legal infrastructure crafted here and for other transitional assistance as needed. Authored by and © Tim Wedig, LAS Global Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Last modified: 7/10/2013