Stuck With the Bill, But Why? An Analysis ... Public Finance System with Respect to Surface...

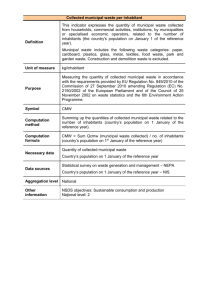

advertisement