How Do People Decide to Allocate Transfers Among Family Members? Donald Cox

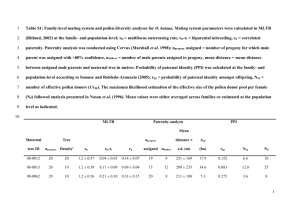

advertisement