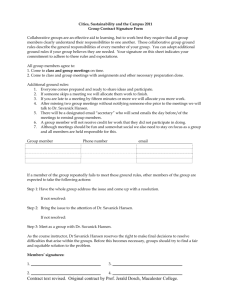

The Economics BducatiJn: A Sur7ey the Literature

advertisement

The Economics

A Sur7ey

o~

~p

BducatiJn:

the Literature

by

Cynthia A, Beniamin

Senior

Hon~r's

fro1ect

ratters)n

September, 1972

3a11 state Uni 'cerE: i ty

~np:lg,s

,.,-

:

/"

._:f-_")i

I

,.

,

(If?':;

.,',:

1('- (.: l

,

"

Introduction

In approaching the idea of

tendency to focus one

lSi

in"estment, ,,1 th2.t i'3,

tt L; t"'le opinion

0"

in~estrnent,

t'ere is a

ie'w on v'J'hat mi::rl:t be terme·j IIc'JD,rentional

in '2'3tment in physical capital.

many economists that in'8stment in hFTIlq,n

capital is eQ1J,gllv i'1"(iorta::1t and liTarrpnts extensi'e st:Jey.

Burton A.

~eisbrod

expresses the idea that hamsl1 capital and

non-h11:n.1an capital contribute; !'to economic growt> 8no welt8.re ...

in v\'hat is probably .'In lnt:::-;rr' eD8nrl ent manner."

knOl>Tle r ! c;:e ::d a population.

iei ea of hunan caDi tal.

ha;~o

'~or

tti,3

n'Jesni te its lmportance, the

n')t :r,11yec' an iElportant 1'c18 in the

l:istr;ry or econ'Jmic thought

9.:';

it has been carried)l1 1n the

Dr~cl ucti-re Dr'lCe,;s t(ncl ec! to cle bil:i tate (,uman capital ... ,,3

-2There were critics of these attitudes held by English

economists, one of whom was Adam Smith who "clearly reco,Q:nized

the iml)Ortance of tlUTJan canltal."

However, lVIarx, a more

lnfluential critic of' classic8,l economics, "ignored human

capi tal co:npletely."

LL

,-

Historically snealdng, neople Here aware of human

capita~,

h)t Ilthe idpa did not have a major impact on economic

thought"

'J.ntil the late 1950 's.

Les ter ThurmV' fee Is that

the reasons for this omission are obvious.

of interest in economic

eljmlnatin~

problems.

~rowth.

II'I'here was a lack

Attaining full employment and

business cycles were the fundamental economic

Income redistribution was considered, but only

direct transfers (rather than a redistribution of human

capi tal) were discus~led. ,,5

The study of human canital has currently resurfaced as

a principle concern of economists, particularly in the analyses

of Gary S. Becl<:er and Theodore Schultz.

1I01Jr current

emphasi~~

Thurow states that

on the nroblems of economic g-rmoJth and

equitable distribution of income has highlighted the importance

of such analysis, for increases in skill, talents, and

knowledge have proven to be major contributors to economic

8'-'rowth •.. "

Another reason for the Ctlrrent interest in human

capi tal fo:r-mation, as seen by Thurow, is that at the present

time

..

"alte~ation

of the distribution of human capital seems to

be the politically preferred method of eliminating both

poverty and income gaps between black and white.,,6

A major component in human capital formation is education.

The role of education on income distribution is an important

-3one.

Paul C. Glick and Eerman P. Miller assert that "in

our complex industrial society, educational attainment is

one of the most important factors in determining the

occupation:=ll and income levels to which

8.

person can aspire. 11'7

3ecker and Chiswick cite evidence that Itschooling usually explains

,-

a not negligible part of the inequality in earnings within a

geographic:=ll area, and a much larger part of differences in

inequality between areas."

8

The purpose of this paper

the economics of hUman capital

on investment in education .

..

s to review the literature on

ormation with speCial focus

The Return on Investment in Education: Private

Individuals invest in education in part for the same

."

reasons that firms invest in physical capital, that is,

they expect the investment to yield a rate of return that vvill

make the investment profitable.

Mark Blaug states that

lIeducation is to some extent at least rep;arded as an investment good rather than a consumer good, because everyone

recognizes the fact that extra education generates a stream

of financial benefits in future years.

II

Thus, the theory

of investment behavior caD be used to explain the demand for

education.

I~ill

9

Economists assume that "optimizing behavior lr

govern the amount that an individual will invest in

human capital.

It is for this reason that Gary S. Becker and

Barry H. Chiswick conclude

th~t

an individual will invest

only that amount which "maximizes his economic welfare. ,1

10

There have been a number of attempts to determine the

individual rate of return on investment in education.

Conceptually, this does not appear to be a difficult problem,

but in

pra~tice

the variables determining income differentials

are extrem31y complex.

'rhe economic literature in this area

stresses both the rates of return by using different computational meLlOds and the problems involved in isolating education

from other variables vJhich determine variances in earninS':s.

The ffii3thodology involved in estimating the returns to

education 7aries froD one study to another.

-4-

The conclusions

-5drawn often depend as much upon the method used to evaluate the

data as they depend upon the data itself.

One method may

overstate :::-eturns because it takes too much into conGideration,

while another will understate returnG because it overlooks

certain benefits.

Of the various methods used to evaluate

those economic returns which a person receives through further

education, Hansen asserts that use of the "rate of return" is

a method much superior to the more conventional methods

used.

bein~

He :"eels that methods using "additional lifetime income

or present value of addi tioTI.'J_l lifetime income r1 are not ne arly

as valuable.

11

In h1:::: use of this method, Hansen observes

8_

high rate

of return to investment in schooling and attributes to this,

the basic attitude that this society has toward education.

He sees thls high rate of return as an adequate explanation

for our "t:radi tional faith in education.

an education is a pm'Terful

~veapon

fierce world which sllrrounds them.

II

To most people,

Hi th "'Thich to attack the rather

For this reason, Hansen

feels that, again reflecting a high rate of

r~turn

to education,

most indivlduals desire to "take advanta,g:e of as much

as they c an.

schoolin~

12

Ii

1110rgan and lVIarttn have found another problem in estimating

returns to education, related to the methodology used.

They

state that the number of hours that a person Horks does not

"increase :3ystematically" with the amount of education attained.

On the contrary, a "voluntary substituting of leisure for income ll

occurs in various forms.

Por this reason, they point out

that if an investigator uses "annual earnings" as a tool in

-6measuring the rate of return to education, he should beware

of these benefits Vfhich may be overlooked.

In $uch q

l1situation, the use of' qnnual earninvs hiees some of the

benefits of education.

Thoug~

a

hi~h

1113

rate of return to education has been

observed by Hansen, it might be important to know how, at

this point in time, the rate of return to education is

c ho.n[""1 nl2: .

Is it risinr;, fallin0: or staying relatively constant?

Along this line of thought, ,James Ivlorgo.n and Charles Lininger

conclude that flthe private and social value of inve;3tment

in education is

than nreir iously implied.

great~er

II

It appears

that this level of value will continue lias long as unskilled

jobs are

e=~iminated

faster than the nu=nber of unskilled li'Torkers

decline, and the demg,no for technically trained people increase

faster than the supply.1I

14

I

In an attempt to see if the '!increase in number and proportion of high school and college graduates during the pact

generation has been Gssociated with a reduction in income

differentials for the se groups,

in the lone: run,

II

it shou.ld be remembered that

if there are no changes in the demand for

workers with a higher level of education, such a reduction

would not be surprising.

we

woul~

have to conclude that the rate of return to further

education is falling.

P. Hiller

If this reduction has occurred, then

However. in the period studied by Herman

(1939-1959), both demand for and supply of highly

educB,ted workers were changing.

Thus, vJ'hen we see, from the

figures of his study, that a reduced supply of workers with

-7educations 1)elovr eighth .'Srade level had "smaller relative

income

p;airci~

tna'l l'1.igh school g:raduates II and at the same t i1Jle,

'we see that the increased supply of college .g:raduates I!did

not affect -Gheir relative income position,

II

the conchwion

dra,,'m is " that the demand for more highly educated workers

has kept paGe 'I'Ji th the incre8.i:3ed supply of tiorkers ... ,,15

In

this way, lVliller implies that the rate of return has at least

kept p9.ee,

Dr is staying rel9..tively constant.

Rensha-~v

maJ{es th8 inference that lithe real cost of

obt8.ini11,,! a hi9:her education, measured in terms of income

forcQ'one and education expenses, has been increasing 'wi th

respect to time,

16

which makes it necessary for returns to

incre9.se in order for an in'festment in education to remain as

proflta-ole as it has been.

data

~'oJh

Hmrever, he also has come IIp with

ich supports tl'1e hypothesis IIthat the returns -from

investment in higher education ho.'1e been declinin'! wi th respect

to time,

sug~esting

that the forces responsible for shifting the

supply of college i\raduates to the right have been strono.:er

than the fcrces shiftinp:: demand. n17

Observin;;r: the tightness of

the job mtu'ket for college graduates today, this hypothesis

seems to

hE~e

some very sound support.

A problem Hhich

thou[jh the

~lick

probabilit~y

and Tl1iller observe is that, e'ren

of succeeding in his financial pursult

is increased by a person's continued investment in education,

this investment does not necessarily lI.'Suarantee II the tlattainmentfl

of that person's financial

~oal.

18

A

~reat

variety of highly

personal factors Can enter in to modify and possibly reduce

-8the import9.nce of a -)articular individual's educational

attainment.

Even after

considerin~

all costs and making

allowances for IInon-educational factors affecting: schoolin,,!,fl

1fJeisbrod feels confident that evidence in the Uni ted states

indicates "formal ed'Jcation does pay in the direct form of

enhanced employment opportunities and, thus, of greater

Fis dat'~. further incJ icates that the f inanc ial

incomes. 1119

return pro::luced by ilT'TeE3tment in education is lIat least

,"lS

gre8.t tt as that return receiveo from "investment in corporate

enterprise.

It

He estimates that this educational return is

H:lTOUnd lO~ for collr~lY,e, and even more for high school and

~

.

elernen~ary

' 1 . ,,20

scnoo

vI.

Lee Hansen states, "Bas ically, the

marginal r9.tes of return rise with more schooling up to the

completion of grade 8 and then gradually falloff with the

completion of college. H21

The problem of isolating the individual's return to

education from other fO.ctors is

'1

c" tnlyblina: block which must

be recognized and overcome, for it not, returns to education

can not be 9.ccurately estimated.

ftexperienc,~.

Certain factors such as

natural o.bili ty, social

clas~3,

family connections.

and other :·{inds of education" have a defini te [3.ffect on an

• d'

. -L

J" S Income. 22

In

.1Vl(Ua_

These variables

hi~hly

complicate the

issue of II megs urinp:: :'eturns to education, for return:s 9.ttributed

to formal educgtion nay in fact be the result of one or more

of these highly per:sonal factors.

If any of these factors ';'Jere

to be sinided out by Surton':Jeisbrod and Peter Farpoff, ability

would be at the top of their list.

They see ability as a most

-9influential variable with re{(ard to "educational attainment,lI

so important that th:::y feel its effect cannot be ignored, for

if it were, the result of education in relation to earnings

would be well overstated.

To their list of influential

variables. Weisbrod and Yarpoff 1;voulc'l 8-dd such factors as

IIschool quality, per:30nal motivation, and pure chance,

II

to

mention only a few. 2'3

In addi tion to lldiversi ty in ability." Bruce 'if. Hilkinnon

sugrests "on-the-10b and off-the-job

trainin~,

market imperfections,

such ai, the lack of :m01'iJ"ledge of onportuni ties, and tradi tionbased "!iITage-salary scales" as possible factors ·which could cause

substanti.g,l \Tariations in the returns that different people

receive from the same amount of education. 24

We really don't

have enough information about the 11relationship bet"·Jeen income

and ability, the importance of on-the-job training," or the

II s ignif ica:1.ce of education in the home.

II

If

w·e could be fully

equipecl with these tools, adjustments could. be made, so that

the

influe~ce

of these factors would not be misconstrued as a

return to investment in education.

Hansen asserts that "full

adjustments for these factors would have the effect of reducing

the relati7e rates

o~

return, espeCially at the higher levels

of schoolinrr:. 1125

BecaW3e of the diverse nature of variables "relevant to

the determ:Lnation of earnings" lVeisbrod rmd

.'

bet"1;'Jeen Hh!lt they call "schoolin,0.;"

variables.

variable'~

l~arp('.f'f'

distinguish

anrl 1'n:)11-schoolinp;1I

The former have to do "\I]"i th the "quantity and qUE'.li ty

of education receivecl1 and the latter lIdescribe the personal

-10characteristics of an individual that influence earniD roc s.,,26

They "estimated that about one-fourth of the earnin::>:s

differences are attributable not to differences in educational

attainment, but to non-schooling factors ... ,,27

Assuming that a high school graduate who attends college

does actlJ.9.11y earn more than one 1.[ho ,Q:'oes to work upon !2.rad1Jation from high school, \'101fle and Smith attempt to learn "ho","J

differences in education affected the

earnin~s

of

hi~h

school

graduates ,)f equal ability or of comparable family background. ,,28

Using high school ranldng as an indicator of ability, they

tried to compare such ranks 1;ifi th the annual earnings of these

students t'ilJ'enty

year~~

later.

The hig;hest ranl;:ing individuals

were reported to have the highest incomes and the difference

in incomes increased with the amount of additional education

that individuals received "after finishing high school. 1129

From the data which

the~T

nresented, \'iolfle and Smith concluded

that "the 'nan of high abtli ty and advanced education rece i ves

substantially better relifard tr:an the man 1I[ho has one but not

both of these attributes."

30

They further conc l'll.de, even

more emphatically thrlt lithe :3.dvantage of higher education is

greate~jt for those of highest ability. ,,31

~l!eii3brod

!:md Karpoff go on to SUbstantiate this view.

Because they found a "tendency for the rate of increase of

earnings o'rer time to be larger for graduates 1<.Ti th higher class

rank,

\I

the:r conclude that those people 1;ifho have the ability

and motivation

neces~jary

to be at the top of , the class list,

are the people 'who benefi t most from an investment in hiEher

-11-

ed.ucation. 32

Rensha11 has not'3d a distinct "tendency for high i2:r ades

to be associated. Hi th increased earnings

and occupations.

II

i~'l

nearly all profess ions

In spite of the fact that high grad.es could

provide a key to financial success, Renshaw finds a p';reat

number of theE8 trbetter students" choosing a profession

HHhich almost never pro'rides entree to the highest income

bracl{ets.

In fact, he observed that nearly

I!

38?~

of "All

graduates enter into lower-pay "professions such as teaching and

the clergy. ra3

To VJeisbrod and Yarpoff, it appears that students of

different ability levels probably won't receive the same value

from a college education.

The "marginal value 11 of such education

will probably corresDond to each person's own ability.

Therefore, they urp;e that direct quotation of lIaverage financial

return ll fi,?:ures of a:tvanced ed.ucation to high school r;r8.duates

be a\"oided, since these

[}vera~~e

~ip,:l1res

may be unfair ,'?ncl

1I34

_.

"misle'ldin!T.

"

Giora Banoch believes that "there is probably a significant

posi ti're correlation betl'Ieen sl.bili ty to earn income--a

combination of natural and acquired ability traits--and the

leve 1 of schooling achieved. ,,35

Renshalv sees as a dis tinc t

possibility that "th8 more ability or natural productivity one

possesses, the more he '(,vill stan1 to benefi t from addi tional

education. ,,36

These vieHs of the influence of ability upon

returns to education might lead us to follmf the conclusions

of D.S. Bridp.;man.

His view of the income differential between

-12hi~h

school and

colle~e

graduates Was substantiated

throu~h

the study of the educ9..tional anri ability patterns of veterans

from World War II 8.ncJ f'rom studies of earnings and abili ties

o~

college

grad~ates.

He feels that ability is a major

reason for income differences between these two groups.

Conseql.l-ently. he sees a

da~l2'er

of overestimating; the IImonetary"

val1.}e of a co11ege education, for the effect of "higher

abili ty

le~rels

and ather such factors have not been q-:lequately

recognized. II)?

Weisbrod concurs that generally, those students who stay

in college have more abiIity, ambition and desire to learn.

Their family backgrounds Hill often ha,re an influence on

their ability to be Dlaced in a position after gradUation.

Their parents are more l1kely to have II,job connections!! to

get them started.

I~

evaluat1n~

incomes in relation to

additional education, it is h9..rd to distinguish tbe portion

of adell tioD9..1 income 11)"hich has been the result of these

personal f9..ctors from the portion which is the result of

more schoolin~.

3"0

Collecting data concerning 9..11 actual investment in

hUman eapital is not easily accomplished.

considering; education to be

8.

Since we are

major "investment in human

capital" 30 it seems much simpler to merely measure investment

in

educati~n.

Becke~

anrl Chiswick state that "investment in

formal education" can be roucrhly "measured by yearE.] of schooling"

}, 0

and this i~formation is easily obtained.~

-13HmlJever, in a s tud.YJonduc ted by crley Ashenfelter 8.nd Joseph

D.

~3uch

Ivlooney, it "'fIas c o:lcluded that "variables

de~ree

as profe s s ion.

level, and field of graduate study. always explained

more of the C!aTiance in

They feel that in

educ8tion, the lwe

earninQ'~3

calculatin~

0<'

than years of 7rad'c-late study.

the rates

o~

return to graduate

the 9.ctual number

0::"

yearE;

II

Of"'.T:'dl~,~te

education a', the lIsel e educatlon-related cIariable II vvoulc1

have very Ilmisleadinz!l reE;ults.

previou1..~ly

has

In striking contrast to What

been stated, they found that the l1inclw3ion

of an ability variable 8.ffected the

estimate~;

of the

coeff ic ient'? for oth or 8duc8.tion-re lated 'iPTiab18 ,; onlv L"l a

very

0:

mar~inal

1~,ivb1y

vFlrj.''3bles,

manner."

ThuE, they corjectur8 that in construct-

2ducated people

II

Fl. IInnmber of relevant control

t 1·"e LtTIe:jtj;·:::-ator "neeci not ·worry .'-lhout tbe lac 1..:

of D.n 'Jbj.Iitvi:ari8ble.

Dlnl),;lble

·~,yd

:;oncl1J~,lon,

,,L~l

If this coulrl be assuJl1ed to be

"C'rocec!ur8~~

conIc! be cOl}i3ic1 er',oly

Gior.8 J-Tanoch oo.;erJe s tb8.t there L3

bet~een

the rates

o~

q

FI

cl

i ;:-·rerenc,,,;

rEturns to whites livinx in the

~outh

south ,clT'? :,io:her tl'an tho:3:' ir the north. 42

from the 1950 (i.S. Census, Glick and Miller conclude that on

on the co11exe level, corrCSDoncJ to "increased earninp.: Dower.

Eowever, in

t~e

Case of non-whites, the

rel~tionship

between

II

on the

obt~in,

8ver~~e,

n hLrhsr return than any other

.QTOHD.

1I

4L!-

S"Jch a vari8nce in the "marginal c f'f ic iency OF investment,

betwee:1.

(1

.

II

i fferent groups of people who have invested in the

same number 0.(' years of education, lef Hanoch to postulate

factors which might lead to such R situation.

The three

major classification] of these factors as he sees them are:

"quality 0':

~;choolinr,

marg-inal marKet discriminsltion, nnn

abili ty--in a br08.d o;enss.

rv:arrrinRl cl iscriminc:!.tion is that

II

situSl.tion in which the "de;rree of discriminAtion" increases

with

t~e

Amount of

e~ucation

that a person obtains.

According to Banoch, it hgs not been 0stablished that such

discrimination actually exists and he feels that much res8arch

would have to be

to

SRY

that

11

don'~

to support its existence.

~e

o:oe ~3 on

if one is inc lir,ed to emph9s ize the environmenb'3l

and social factors,

then the disparity between the rates of

return to schooling in the two racial qroups &h1tes and non-

"\<Jhite~ CRn be 'lttrih'lted entirely to some Porm oP- iscrlminetion

1

aqainst non-whites

i~

the schools, in the current labor market,

or in the accumulated social burden. 1I45

t::J to nOli'!, in considerin0 the return5; that an inc'ividual

receives~rom

advancsd erlucation, we have been very concerned

with personal factors which may enter in to alter ths value

of inv8stment in erilJcation

~or

8

specific individual.

-1.5n~ver

We have

re8lly mentioned the significance of where this

Surely it m8.kes a

difPerence which institution one attends, otherwise people

~voul::ln

I

t 'worry so much about the schools

attend.

~raduatets

The high school

not be such an import8.nt L:;sue.

of' !fd i

tJhich the ir children

choice of schools would

Renstal,1T assertE3 that bec::3l..1se

in t"le quali ty of education, rl i

~~ferences

f:P~rence~o

in

the quality of' students, and eifferences in the quality of

home

en\jironment~)1t

dr8."t·m

to mention only

9

few

~8.ctorEl,

th? concluc;ion

shoulcl be th8.t "it m'J.kes a considerable dif'f'erence

what school one attends.

LV::

II

0

In aporoaching the topic of quality education, Richard

Raymond faces the question: what is quality education and

how Can it be :r.easured?

Contrary to v'That mig-ht seem common-

sense an(l::;asily argne8ble, he concludeE; that " ... the studentteecher

r~tio,

the percent of teachers

teachin~

in two fields,

current expend i tures. or the adequacy of Ii br'3.ry f8cili ties ...

are not ahT8.Ys accurnte indicators of quali ty.

evidence 1iV3.rrants "only a very guarded

measure quali ty,

II

u~)e

II

He fee Is that

of E;alaries to

e 1T en thoup:h he conceded th9t hig'l'o;r salaries

can have a definite positive ef:ect on the educ8tion 1iVhich

we receive. 47

In in'Jestig8tinv the qU81ity of education in different

school

Some

sys~ems,

stres~3

objectives are found to be widely varying.

col1eQ'e prepar8tory courses, while othen3 weigh

technical or voca.tiOl!al type tr"Jining more heavily.

the

invest~lgator

'Thus,

must pose the question of' the 'Tallo i ty of a

-16study which lumps such systems

quality index.

Rnymond, in

to~ether

me~surin~

to develope a

the quality of education

concentrates on the idea that the level of prenaration

higher education is a measure of qua1ity.48

~or

The

Return

--_

.

on Investment in Education:

Social

In th3 previous section we were more concerned with the

inc j.vidual benefi ts uhicv> can be obtained through flJrther

educgtion.

"In addition to these,

it is possible th0t other

sections of' the commllnity--members of the same family,

ne ifFhbour[', work collegue s or the community ing'eneral through

~overnment~l

8~encies--may

from the edUcation

to

0'

eXDerience economic

some ();:' i tr3 members.

would be macJ e in rel ation to such "wid er

:3ince any decisions

11

m'Jre on education by agencief.; such

~3pend

side-ef~ects

a~:;

the gO\fprnment

con~;equence

s" of

educating3.n individual, thec;e conseqv.ences "should be evaluated

in a simila.r m9.nner to the privAte benefits.

ing "education in economic terms,

If

11

Now in aDDro,:>,ch-

vve must realize that there

is a "need for some identification anc1 me8.surement

0"

the

communi tY-l'lide costs and bene!' its assoc iated vITi th education.

49

Those benefits 1jjhich a communi ty receives from the educ8tion

of the individuals which comprise it can be termed external

ef~ects

of education.

However, these external effects are

not always bestovTeo upon th'lt area which financed 'In individual1s education, for some of these benefits accrue to the

l1ind i'1io.ua11 solace of residence," which is a highly flexible

-'1" ')c t or.

50

Because movement from one area to 8.nother has

become an everyday, commonplace situation, problems concernin£r

the financ:Lal aspect of educ8tion have arisen.

If the distrib-

ution of educational funds is to be beth equitable and efficient,

-17-

-18the effects of migration must be consid?red.

o~

educ8ti~~

indi~iduals

The burden

may be taken on by one community,

while 8nother community will benefit, without cost to

themselves. 51

The problem could indeed be severe in an

areA- where out-migration was consistently greater tha.n

in-mirrrati cm.

Becker divides the "economic effects of educationll

into two

(1) the effect on incomes of persons receiving

p~rts:

the edUcation;

(2)

the effect on incomes of others.

In estimating lIag:zrei1:ate 30cial returns,

If

52

Mary Jean Bow·man

states that this second effect creates a definite problem.

"Arrfrregate social returns ll to education might be looked at

as the sum of individual social returns.

type

Of'

ev~luation

However, if this

is used, we are disregard ing inte:r8.ction

between individuals, that is,

disrei1:ardin~

the effect that

the educatton of one person has on the education

"The total

~)ocial

o~

another.

return may be larp-'er or smaller th;:tn the

sum of ind tvidual returns "fiewed in isolation from each

other unle:3f3 a correction for these interactions is made.

As BOlNman sees it,

1153

if we look at returns from education

in the Ion,! run, we must incltlde the effect that a parent's

education

~as

on his children.

She chooses to

re~er

to

this as a 11defferred return,

II

and a lIcontirbution ... to the future

ef-E'iciency 0:' children. f154

Education as Weisbrod sees it is

lIa means 0::' inculcating children wi th

~~tand8.rds

of SOCially

desirable attitudes and behavior and of introducin3' children

-19to new opportunities and challenges.

lI

By means of education,

our children are encoura,Q;ed to I1de',relope greater awareness

of, and ability to p8.rticip8.te effecti,cely in, the democratic

process. H55

Educ9.tion of children in the home by the ir

parents exemplifies

overlooked. 56

~

benefit of education which is often

We must take into consideration the intergener-

ational effects of education, that is, the "influence of

ec'lucation in ene generation on atti tuc.es and educ2.tional

attainments in the n3xta:eneration. ,,57

In focu~~ing on

"current" benefits s'J.ch as increased earnings, future returns

"in the form of intergeneration benefitsll are ignoreo.

is important that

thi~3

a~;l')ect

It

0" returns to investment in

education be considered along with the more obvious returns.

58

Data presented by William J. Swift and Burton A. Weisbrod

indicate th8.t the "interveneration rate of return .•. rises

as the parents

level,"

T

eduC9.tion incre8.ses thr01Jgh the high school

then drops with parents

beyond that level.

I

incre8.se in education

"Higher costs of college H and "foregone

income" are cited as reasons for this decline. 59

Ways to increase the return to society on

investment 8r8 alw9Y·'3 bein2: considerec..

education~l

Seme investigators

find that m8.ny people whose productivity could be incrased

through advanced

8dl~Cation

ne.'er make the necessary in,restment.

Unfortunately, it often happens that those who possess the

talent and abillty to :'urther their eduC!'ltion are the same

people who lack the "moti 'Jation or

'TIean~3

to do so," and those

-20-

who can afford it ar::; not able to handle advanced education

because of the 1I1ack of mantal ability" necessary Cor such

a pursui t. 60

'wolfle and Smith observed tha,t

II

many high f;chool

graduates" who are cle8rly marked as college material--as

measured by

~rades

in school Rnd performance on intelligsnce

or aptitude tests--n0ver enter college.

However, they felt

that this is caused not so much by the lack of sufficient

r'undf3 as it h; by the:; !tls,ck of ec1ucational moti-;g,tion. !;61

:;ary S. Becker also recognizes the fact that many high school

students 1/vith high Q'Tac1ef] (and/or IQ's) do not p,ttenCl

colle8:e, either foreinancial or

reasons.

He 'is

o~

~enera,l

f,g,mily backgroun:'1

the opinion that if more

o~

these high

ability students went on to college, the average return from

college could be increased.

"An improvement in the quality

of college students rlay well be 9,n

ef~~ective

contributiJn of college education to

liV-R.y to raise the

pro~ress. 62

11

A mg"iJr ,Q:'oal of bot!". education and manpovTer policies is

the proper allocation of resources.

of the

cd~cation

Qnd labor markets

The interdependence

see~

by Mark Blaug nRturally

implies that separate consideration of education and manpower

decisions Hould not be'ralU. 63

He emphasizes that tfmanpow'er

forecasts in a developea country ... must take account of the

likely expansion of ccucation.

t'

our vari ,""ble" :

Ii

His arguement

make~3

l.we of

lidemand a,nd supply in the edl.'C'3tion marl{:et,

ano demand and suppl;y in the la,bour market."

I:

one considers

that all of these ar( Gubject to a certain amount of control

by public authorities, one might say that they are all

IIpolicy variables.

tl

However, as far aE Blaug is concerned,

only supply in the education market can re8l1y be considered

8.

ilpolicy

~Iari8.ble,"

since the others are contrcrl1ed only to

a "limited ctegree. 1I61.j-

Thus, it can be ,sqid that education

does not necessarily create jobE for its graduates.

However,

if education is channeled in the right directions, the skills

vvhich empl::>yers are dernandincc of their labor force vJill be

llLabor-:orce

the skills carried away by our graduates.

~lkills

Il

cuttin:<:

ca:1. be be tter matched with Uernployer needs, II thus

::"c

C; O'IJn

on unemploYlClent .<)

.sc1 cially, econonists want to rationalize investment in

educat10n to moximize socisl return.

Investment theory

should a1d an administrator in determining the proper

allocsti on 0 i' re s ourees f or his ins ti tution.

An economist, in

aDplying eeonomic analysis to higher education, do':;s not

want to taJes r2sourc(=

G

aWAY

"rom sduco.tion

b~J

cutting costs,

but is "interested in achieving ... 'best use' of 8.'J8.ilablf::

rescurces Hithin the

~'rame1;\ror}c

If traditional in;restment

basic criteria to work with.

of

~/aluei3

tL80~y

that

t}':,'O

'3c!ministrators

i!3 "liJplied, we h.'3.,re tit>JO

The present value method can te

used when '::. decision must be mode concerning hro alternaticres

which can't; both be undertaken because o' lilited copit81.

" .. . The nrc'ject v!hose discounted prec;ent

Dursuec1 •

II

-c].'F:

is gre"ltest is

The margin9.l rsturrw methorji ..' iclss Cllloc8tinrr

-22"cap! tql h=:tT,feen any two inirestment ol1tlets in such :') 1/fay that

the returns on the

are eqllal.

II

l~lst

unit of caDi tal p18ced in each outlet

In this situation, the

US2 :ulne::.::~;

0""

the

abo~re

criteria is limited because oP the many objecti7es that an

pducatio1181 ins ti tutlon m':iY have and bec8.usc

0 f'

the dL' C' icul ty

of quantitatively evaluating its returns. 67

In order to mal'.:,:,; use of the traditional criteria, J ennE-tb

De i tCll SUi7:'';'SSts that the administrator must: irst clesl.rly

state his ob,jectiires B.nn knm'l their iTT'.portance

j

h::: shoul]

recognize ':;hose variab18s uhich p.re wi thin his control and

those which are "externally determined.

a,'lare

0:

II

Third, he must be

"lvhers relations exist between Changes in the

rele'!ant rrariables and achie';rement

0:'

the desired ob,iectives. 1168

The ",whem::;tic framework" presented for c:ealinp; Hi th the

certain r2.tiNi.

'rhe -"irst r'?tio (cost ratio) is tltlw r8.te

at which ... tvw ~lternati~!9 rl.ctirrltles m.'3y be substitut2d f'or

each other -while the total COE3ts are being held const;c:l.nt.

If

The second r"?tio (return~ ratio) is the "rate R.t which the

two varl"1.bles may be substi tut,sd

total

bene~'

-;:~or

each other 1lJhilE: the

its arA bs inrr helc1:)onstant.

II

An opt lmum OCC1JrS

when the cost ratio end returns ratio !or a particular pair

oP ob~ectives are equal.

If they are not equal, then all that

is necessary to bring about equality is substi tution

"or the other.

" •• . ic~

o::~

one

one variable's cost adv9ntage is 12:';s

thgn its rr: turns ad 'Janto.ge Ofer ano ther -.rariable, the :' irs t

-23vicerrersa. 1t69

tfnf'ortunately, the ITea~)1)ring

remains to be somewhat nf a

~roblern.

("If'

De itch fee Is that ecren

tt'.)ugh ths results mEW be "less than perfect,

will be more meanin9,: 1 ul than

..

j_ t'

benefjts

It

these results

n.) measurement 'Jf bene f' its

were attemDted. 70

Sdl.1cat:Lon plays a d lstinct role in economic gr-q,lJth and

de 'elopement.

As IDlt forth by James

Mor~8~

an~

Martin 8avid,

increased in estment in education, whether public ~r

has certain economic benef'its, and can be thought

If as yielding a SOCial rate o~' return on the inifestment.

This ;)~cial \'alne :J f' return inc Iuds s bene fits such as

s;r:reater flexibility 0f the labor Porce, the 'Talue of an

inf::,rrnecl !'3lect)rate, the greater en 4 0yment of life and

c1J.lt'J::-e, as 1o'1el1 aE.l the m':>:'3t ,obvi'lw~ benefitJf the :;.c:reater

pricneti'!i tyJf eclu.cated w:Jrkers. 71

priva~e,

The pr")cll,,-c'::.i'ci ty of workers can be much enhanced by the educatjonal

process.

1t

pro(Juce~;

"a lab"'r force t-at is m-:Jre skilled,

fiJre adaptable to t"8 needs of a changing economy, and more

likely to de'relope V"e lmaginative ideas, techniques and

products wich are critical tJ the processes of econ,rnic

expansion and social adaptation to change. n72

2:d1o'larcJ

p.

Renshaw ha:] rJbser'red that lithe trend in labor pr-,ducti vi ty is

almost identically equal to our best estimate of the trend in

educational attainment (If t r 8 labor force.

n

?3

Econ'Jmic growth can als- be considered in relation to

the quanti tv ane1 the quality ·:Jf education.

In the past, the

supply of ec111cational iJpportuni ties has been increasing at

a rapid rate.

Howe~er,

it is now no longer possible f'or this

rate of inGrease tel continue.

Edilvard F. Denison cites the

-Pact t''lat in order for the "contribution of education to

-24grov-Tth" to remain constant or increase. vve must therefore

cine! a factor vJhich 1'1ill take the place of "quantity" of

ed uc ation.

He emphas izes

th~3t

"9.

sharply 8.cce lerated

improvement in the qugli ty of edUCation Hould be nes,: eel

to pre'Ient the contribution

decll n ing.,,74

0:

education to grm'ith from

Conclusion

liThe basic questions

un~1erlying

much of the research

on the ecoc1omics of' pducational investment

on hm>! much

lOCUS

more or how much less we should be investing in education in

gener9~1 as we 11 as in 'farious spec i ic types

P

0'<>

education. 1175

The values of these nducational outputs must be weighed

ag~inst

the value Jf resources which go into the production o.c·

education.

In choosing Wh9.t time and money we should be

allocatin u to

~ducation,

"benefi t~)

costs of alternative uses" of our educational

resources.

;::lJ'lrj

we must also look towards the

Only when such factors ha-Fe been taken into

consideration, can

We:

bep;in to "choose wisely. 1176

Unfortunately, we h87e not answered the question

01"

"hC1i'l much more or hovr much less" should be in;rested in

education.

Are we uncerinvesting in education or could He

qui te poss:Lbly be ovsrim,resting in education?

conclusion:, be drawn?

Can any concrete

Along this line of thinking, Gary 3.

Becker has stated his opinion very clearly.

"The limited

a,railable f;'.:-idence dlcl not rereal any significant discrepancy

between the direct rEturns to college education and business

capital, and thus direct returns alone do not seem to justify

increasec1 eollege expend i tures.

expend i turE; S.

IV:::

II

In order to .justi fy increased

would hare to come up with some s igni f i cant

external or indirect returns to college education.

Since

the economlst'eels that litt13 is known about indirect eCrects,

-25-

-26-

and the tools :or me8.surlnrs such

eL~ects

"a firm judgement ab:)ut the extent

O!'

colle~e education is not Dossible. 77

are limi ted,

underimrestment in

Thus, in conclusion,

it must be <>aid that a great number :){ questions utill

remain unanswered.

~he

2earch for the answers to these

questions and the seqrch for new questions will ccntinue.

Schultz summarizes t'lis very aptly:

is always facing unknovffis.

"An unfinished search

'There is no royal read.

The

ril2;ht questions tel Dursue are among the unknelwns in this game.,,78

Endnotes

13urton A. Weisbrod, 11 Investinf;?: in Human Capital, II

of Human Resources, To1. 1, No.1 (Summer, 1966), p. 21.

,Jo~rnal

23urton A. Heisbrod, IIEducation and Investment in Human

Capi tal, II Journal ..2£ Political EconQ!gY, 'tol. 70, No. .5,

Part 2 (8ctober, 1962, Supolement), p. 106.

3Lester Thurmv, Investment in Human Capital (California:

Wadsworth Publishing ComD8ny, Inc., 1970), p. 3.

4rrhurmv, p. 4.

5Thurow, pp. 5-6.

6Thurow, p. 2.

7PalJl C. Clicl: 9nd Herman P. Miller, "Educational Level

and Potential Income, II American Sociological R~ieJ:I,Tol, 21,

No. J (June, 1956), p. 3,:)7.

BGary S. Becker and Barry R. ChisHick, "Education and the

II

A merlcan

'

H'

'

R

'

--.r'apers an d

-"-,conomlC

~~,

Proceed ings , 01. 56, No, 2 (f.'lay, 19bbJ, p. 300.

' t rl'b u t'lon OL- C "J::arnlngs,

'"

'

D

,1S

9IVlark Blaug, II AYl Ec,:)nomi c Interpretat ion of the Pri 'fate

Demand for Education, II Economica, 101. 33, Ho. 130 (]\}ay,

1966), p. 1(-)7.

10Becker and Chiswick, p. 359.

llW. Lee Hansen, IITotal and Pri ate Rates of Return to

Ine·estment in Schooling," ,TournaI of Political EC2!!/:'mY, ~01.71,

No. (April. 1963), p. ll-l-C.----- -- 12Hansen, P. 140.

IJTamei3 Morgan and lVlartin Da'id, "Education and Income, II

Ql)9.rterly i (iurnal of Economics ,;,Tol. 77 , No. 3 (August, 1963),

--~-,- - - - - p. -1-37.

----

14,Tame s IVlorr:can and Charles Linin.R:er, lIEducation and Income:

Comment,1! ~uarterly rournal of' Economics, '01. 78, No.2

(Hay. 196L()', D. 3l~7. - - - - - __

00

15Herm9,n F. Hiller, "Annual and Lifetime Incoro8 in Relation

to Educati:m:

1939-S9,!1 American Economic g~~!i~, ~01. 50,

No . .5 (Dec3mber, 196u), pp. 964-5.

-27-

-28/

l!J2:d~'rard ~. Ren3haH, 1t3stimating the Returns to ~ducation, It

RevisH r:~~ =:conomics 3.;.~19_ ~tsti.§tic§._L 101. 1+2, >;0. J (AU9;ust, 1(60),

p.-- 322 .. -.-

-~--~-"---'

17Renshaw, p. 322.

19~1ick and Miller.

D.

307.

19\'18 isbrocl , "In,-e:3 t inn; i:'1 Human Capital.

!I

D.

20-,

. b ro.d ,

welS

11

p. 1l.L

22RerU3hsiiJ,

II

In,-e s t in;:r in

;~1)man

Capital,

lli.

321.

P.

2:3BvrtrD A. \lJe isbrod nnd ppter YarDoff', II I~one tary Returns

to r;olleq":; Edvcation, Student Ability and College ~uality. 11

Re'iriew ::-'io'-'-"oC Sconomics 3.nci ~)tath;tics. 'oJ. . .sO, l'\:L h (lo-crem':Jer,

-,.- , ---- - '..-----.-19

I,

'J ..

,. / 1 .

--~G\'J"

2 )CJan

II

_ L "en

.. )

,

p,."

26, . .

~~elsbrod

IiiY ')

1-"

and.

..

arpoft',

p.491.

2'7',I[eisbrod and Larpoff', p. ,1./.97.

2d Dae 1 VIol fIe and Joseph C;. 'smith, liThe Cccupa tional i alue

of Sducstion f'or ~:3u1Y~rior Eip:h 3cho:::.l Grad'Uates, II ~'ourn'll of

,liiEber Ecl-l90 t,ton ,

01. 27 (April, 1956), p. 201.

20,//,J-0 J'

_1 1 e and Smith,

p. 203.

3 (Jill 0 1 fIe and. Smtth, p. 2Ci7 .

3 li,vo If'le ane! 3mtth, D. 202.

3;~'vJeLjbrod and Iarpoff, p. 1+97.

3JRensh8,H,

D.

319.

34~eisbrod and

35'~'l' '. . . ·r8

arpoff.

j

P. li92.

ual1nch 111\1' :~cnnorr'l' C Ana]Y"l'

of' Darn

l' 'no'"

1 .' _

W

.......

t-- u

Schoolin.CJ:," Journ,'3.1 o'f Human Re~jQllrce~). '01. 2. ~'IO, 3

(Sul11mer, 196~pp. 323"=4:---- -------\.~,

'.-./.

,,'

-

3 6Ren3haw,

~ ~

P.

1

~

320.

J.....

'.

- . J ' "'-J _

•

~

~~

t.

0 2 1 ' ;C'

')

:_

9.nci

-2937D. S. Brid£:man, "Problems in Estimating the

'alue 0" College ~ducation," Review $f C:~onomics and

~tatistics, '01. 42 (Supplement, 1960). P. 181.1·,

~'j()netary

3: j 'il e i sbrod,

,I

39'weisbrcd,

"In,resting in Human Capital," p. 10.

In1e sting; in Human Capi tSll,

I'

p. 12.

4C3ecker and Chiswick, p. 368.

41crl~y Ashenf'e Iter anc; ,Iose"l)h 1). IV]c,oney, "G-raduate

Sducation, Ability End E0rnin9:'s," RevielJ" of Economics and

Statistics., 'cl. 50, ~\-o. 1 (?ebruary, 1968), pp. ['5-(';".--

42Hanoc~,

p.

325.

43 Gl ick and Miller, p.

311.

44Rensha't'T, :0. 3'22.

45~anoch,

D.

327.

46Renshaw, p. 319.

47Richard Raymo'1d, flDeterminants of the Quality of

l-rimary and SeCOnd8TJ Public Education in 1v'est in':inia, 11

,Journa:b of EU1]ill1 Resources,

'01. 3, l\Io. 4 (Fall, 1968), p. 46q.

49JV:artin C I Dono:rhue, Economic Dimens ions in .2:cl~9_atj_on,

Aldin'Atherton, 1971), n. i6.

(Chicai~o:

5 C\veisbrod, IIEd'watton

SlvJe:isbrorj,

Investment inciuman Canital,

l!

D. 120.

IIEd',wation ani Imrestment in Human Canital,

II

D. 121.

'lYle!

52Garv S. Becker:' , ", nderiYllrestment in College EdUcation,"

American ~~~~ Re~ie"J, lancc!rs and Froceedings, Tal. 50,

No.2 (rv:av, 1900), p. 347.

5JfvIarv .Jean Bo'tfman, 1ISocj.al Ret1JrnS to Erl1)cation,

International SOCial Science Journal, ,01. 14, ~o. 4

TI9h2T.-D~--·647~-·--

II

---

54Bow~an, p. 658.

"In,re sting in Human CaDi tal,

11

p. 16.

"In-resting in Human Capital,1I p. lS.

57,,1'11'

,. S'iJL

' f t c~n\J

a

-'l

;vl lam ,J.

3vrton A. \,~eisbrod, nen the fiionetary

7alue o~o Sdl}caticm IS InterP-.'eneration Effects, 11 ,) ourn-)l of'

j:;01ltica15conomy, 101. 7J, :w. :5 {Oecember, 1965).0.643.

-305:3Weisbrod,

IIInIesting in Human Capital,lI D. 15.

59Swi~t and Weisbrod, p. 647.

60Glick and Miller, p. 308.

61Wolfle and Smith, p. 206.

62Becker,

"CnderinJestment in College Education," p. 354.

63 Bl au .Q;, p. 182.

64Blaug, p. 166.

L

~

O)ideisbrod,

IIIn'Jestinhr' tn Human Capital, II P. 13.

66l\enneth Deitch, IIS ome CbserIations on the Allocation

of Resources in Higher Education," Review of EC.QQ2mics .§ond

Statis~ics ,701. 42 (SuPDlement, 19bo~. 192.

6?Deitch, pp.192-3.

68Deitch, pp. 193-4.

69Deitch, pp. 194-5.

70Deitch, P. 19C3.

71Mor,gan and David, D. 423.

72We j :,brocJ.

"In',resting- in Human Capital,

11

p. 10.

73Renshaw, D. 319.

4

7 2:;dward P. Denison, "Education, Economic Growth, and

Gaps in In=ormation," Journal of Foli tical Economy, /-01. 70,

No ~ S, J:-'2crt 2 (~~ctober-,-1962:" Supplement)-: P.12?":""

75Theodore H. Schultz, "The Rate of Return in Allocating

InlTestment Resources to Edl.lcation, If Journal of Euman Resources,

it)I.

2. No. 3 (Summer. 1967). p. 293 (Introductr;n).

76Weisbrod,

"In'.'esting in Human Capital,

17

p. lI.

77Becker, "Underinvestment in College Education," p. 354.

70Theod ore itI. Schultz, The ~conomic ~lue cf Education

(New York:

Columbia University Press, 1903), D. 69.

Bibliography

1 ter, ()rley, and '. o~~eDv] ;). Honney.

lI::;raduate ~c1 ucation,

Abtlt t;il and E:;arn~Lngs. II He 'fiew 0:£' Economics and Statistics,

'10 L

~ IJ, No. 1 C"e bruarY:- 19 b8T: PP -:--78 -dh . --_. ,--

A~;henfe

Becker,'ary S. ""nrj':rin"estment in Colleg;e Education. II

Americ3.Yl Economic Re','iew, Papers 8nd :eroceedin,Q;s,01. 50,

Eo. 2 (May-:l96o';', r'Ji;'-:-'-'346- 354.

Becker, (~ary S., and Barry R. '~hiswiclL

lIEducqtlon and the

Dh;tri:lut i'-'n of j~arning;s. It American Economic Re' ie~T,

Fapers and proceed ins:;s, '/cl-:--Sb,Nc;. 2

(l'ay~' 19t5j\~

pp,

3~~"-369.

IllUl

Econ:::,mic Inter-oretation oz' the Frivate

Bmrm8.n, E'?TY ,;SOD .

"8:)ci"31 Returns to Ed-lc8,ti::m. I! I:vlternatLmal

Soeip13cience .':":"),Inr:.,l.

cl, ll~, .-=. I-J. (1962), 'po, S47-'~~59.-

Det tcr, ~'::::1neth.

I1Snme Cbser'!!:"tions on the Allocation cf

Re::,;)l:!:,';c'; in'figher ~cl;lc<J.ti')n. 11 Reviel J :,f Ec'::m)mics"",nd

It:J.ti ',:C e ' :: , ' 1 . ' 42, (3l"J"(:lement, 1960 )-,-Ym, 192-19:::-,o

£i ' .

1tE(]lJ.C8,ti~)n, .:~c0nomic Gr:)"~Jth,

slno r:aps in

Inf -;rfJati'n. 11 .J ()urnal ,Y." Foll tj cal Econc 2 , "/Ci 1. 70,

1';,:;,

art 2 (Cctober,1962, Sllp~~lD'r!"ent), pp. 124-12'L

~'?n.i~;~Yl,

~~~d~.rar~t

Glick, L::'-apl C., ,9.nd Herman r. I::U,ler.

lI~c'!ucatjonal I,evel ani':

Fotentlal :rncome 11 American Socioloo;ical ::1e'Tis"J,

01., 21,

£:0. 3 (Jnnc;, 195 ), -:;:'p, 3(:7-312.

<

II

Hansen, vI, Lee.

I!~otal anr1 Fri ,,rato Rates of Return to Investment

in Sclrosllw' , 11 ,ournal o~' lolitical .~ccn~'1lV,

,,1, 71,

1'1·::;. 2 (April, 19~;3), u'o.12·(j-l4G":-- --~

!VIiller, Fe:C'rnan F. I1Anm1 al and Li""etime Income in Relc:1.ti,on to

2:dllcatlon:

1939-59. II American Economic Review,

01. r:;(\,

1';0.

r::. (DSCCf(lbcr, lQ(.U) , Dr:. 9b2-9f)b.--31-

-J2Morgan,

anes and Ma:,:,tin Da,rid.

"3;dllcation and Income. n

Quarterly .Tournal of ,:SconomicQ,IJL 77, No. J (A1.~gust,

), '3-7-19 2 J";J' Y"" I_y/'2'<J--i"'_

f_·'..J~

...... J

~

Morgan, Janes, and Charles Lininger.

!lEd1.1Cation ane Income:

Com:rr:ent, 11 {~uartt;rl¥journal ·:)f Eccnelmics, 'elL 7'(;, l-:o. 2

(r>lay, 1964),1)1), 34c-3"h7.

01Dono~hue,

Chicag~:

Martin.

Economic Dimensions in

Aldin'Atherton, 1971.

Educati~n.

Raymond, Richard.

!1 iJeterminants of the Quality of Primar:v

and Sec:mriary =ublic Education in \vest Virginia. 1I Journal

.:2f_ H1..:!:ffi;~y! ResoiJ.r~~,7ol. J, 1';0. 4 (Fall. 1962) ,co. 4r:;O-L~70.

Rensrg,"t'T.

F.

1f"2;stimatinr<: the Returns to Sducatiol1.

Re'vie1;'T of Scnnomi.cs and Statistics, 101.42, No.3

TAugust~'-l96o J, 1)9· 318-324.

::'~dward

11

SChlJltz, T'1ec:)(J"re vi.

The Economic l-alue of Edy,catlQQ.

NevT Ycrk::::! IJ 1 umhia Uni -I ;~rs i ty lYe s s, 197)3.

Schul tz, T:180(J ore H.

lfTr:(::: R'3~te of Return in Allocating

Iu/estment Resources to Sducation.11 Journal :)f EUman

I!£~~~e~,

.,1. 2.1:0, 3 (3uroIDer, 1967T~ p~O-:- 293-=Y)9.

S-';vif't, \'iilliam .1., ami Burton A. itleisbrod.

11'1 tho jv;onetary

Value o~; 3r:l.ucaticr.l s Inter[f'3neration E!":~sct(), 1\ JOlJrnal

;:..

l"t·

E conom.z:,

"'

.. o1. "73 , ,'1',0

r

(., (nol"P

2::..c:. ;!;.$

.,L l ca 1 _

.,

lJ~ ~ ~rr b(~

::..r, 1965), ~;It:3-649.

!JD.

Thurow, Lester.

I~.:.:.§:stment in ~~~I!lan Ca21ta:J:,

\'J9.c!s~vorth .'ublishing ~om:)r.:my, Inc., 197C',

::ieisbrod, :3urton A.

Calif'ornia:

IfI:rsesting in Euman Canital.

II

.Tournal

S~: J1umt~ R~~£.E: s ,01. 1, Ho. 1 (S1.nIlm;r, 19(6). p~o. 5-2L

Heisbrorl.

T~llrt'):::J

,To1.Jrna~:

A.

"Erincati')n an(! Ino,estment in Ruman CaDi tal.

5, Part 2

:)C .:~liti.£Ql&co_nom2[, 1:)1. 7(1, 1'0.

((~ctobc~r, 19(:)2, S1.J1Jplement), pp. 106-l2J.

l"leisbrccd, 3urton A. s·,ne} letcr ~. arpoff.

"r"ionetary Returns to

College Educatior, StU'.l ent Ability and College Quali t:v. 11

Re 'iew of Economi cs a~1c' 3t9~tist i. cs , To1. SO, No. 4

70,",~r0m1-J-c-:--r

19{:.0

\

p'-p'-.. 1i91':l'

0"---'

t 1';

k.

,

~ '-"" U) ,

'-t'

_'--t'./ ( ..

'J

' '-" •. !

'dil~"lnson,

Bruce ~J. flrresent'alues of' LL'etime Sarnln"s '-'or

'Ji:"f'ercnt :)CCllDations _ 11 ,Tournal 0" roli tical Econornv,

'''nl

'I'

cj

6'

._--:'

- .-"

~(

1·,0.

( ([.. ec·~m b co.:or, -1-9~

CO;,

PrJ- • -rs7:-S72

.)

_

("1'.

0

u-

•

!I

-33-

vJolflc:,

Dail, anrj ,~oseph r;. Smith.

liThe 'cclJ.pational T'alue

EduC3ti:)J:'1 ~orSuDerior l;il=':y:-Scl'l"''')l r:raou8.tes. 1I

1:2urn~1 S.2.[ nigt~r Br3 ucati'''):Q ,

01. 27 (Aprj1, 1955),

C""

•

DD.

201-212. 232 .