RESEARCH RUNDOWN—ACTIVE LEARNING STRATEGIES

advertisement

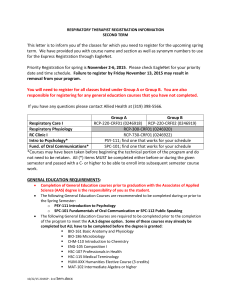

RESEARCH RUNDOWN—ACTIVE LEARNING STRATEGIES Executive Summary This research rundown includes an annotated bibliography of twenty-seven quantitative studies having to do with integrating active learning strategies in the classroom. Strategies demonstrated included peer-to-peer teaching/service learning, class discussions/forums, role play, interactive lecture demonstrations, debate, interactive social media technologies, group work, clickers, and other miscellaneous strategies. In studies involving graded tests, results were mixed. Some studies showed little difference in test items between the control and experimental (active learning) groups while others showed that the test items connected to active learning assignments scored better. In student perceptions of how well they learned and how interested they were, the active learning groups scored higher on most studies. Critical thinking skills also appeared to be better in the experimental groups, as well as interest and enjoyment (though in at least one study, students balked at what they saw a heavier work load). Unfortunately, in the studies that showed a significant difference in scores or perception, quite often there were multiple strategies used, so researchers have no way of knowing which strategies were the most successful. Reference Population Benware, C. A., & Deci, E. L. (1984). Quality of learning with an active versus passive motivational set. American Educational Research Journal, 21(4), 755-765. Forty-three first year students from the University of Rochester's introductory Psychology course, randomly assigned to two groups: 19 in the experimental group and 21 in the control group. Purpose/Question s Will students who learn with an active orientation be more intrinsically motivated to learn and learn more than students who learn with a passive orientation? The active orientation was created by having subjects learn material with the expectation of teaching it to another student; the passive orientation was created by having Findings Though little difference was found in rote learning tests, students in the experimental “learn in order to teach” group saw themselves as actively participating in learning more and rated their interest level higher (7.13 in comparison to 4.43 in the learn in order to take exam control group). They also reported greater enjoyment and participation (7.0 and 2.11, respectively) as compared to the control exam group who scored 4.67 and .76 respectively. Braxton, J. M., Jones, W. A., Hirschy, A. S., & Hartley III, H. V. (2008). The role of active learning in college student persistence. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(115), 71-83. subjects learn the same material with the expectation of being tested on it. 408 first-time, HYPOTHESIS 1. full-time, first The more year students frequently in eight students perceive residential and that faculty religiously members use affiliated active learning colleges and practices in their universities. courses, the more 59.8% were that students female and perceive that their 12.8% college or minorities. university is committed to the welfare of its students. HYPOTHESIS 2. The more frequently students perceive that faculty members use active learning practices in their courses, the greater is their degree of social integration. HYPOTHESIS 3. The greater a student’s degree of social integration, the greater is that student’s level of subsequent commitment to the college or university. HYPOTHESIS 4. The greater a student’s level of subsequent After controlling for a student’s demographic information and initial institutional commitment, student perceptions of faculty use of active learning practices have a positive and statistically significant (β = .136, p = .001) impact on how students perceive their institution’s commitment to the welfare of students. The relationship between active learning and a student’s degree of overall social integration, however, failed to provide a statistically reliable coefficient. However, student perceptions of the extent to which their college or university displays a commitment to the welfare of its students exert a positive direct influence on social integration. Social integration is positively and significantly related to a student’s subsequent institutional commitment. It was also indicated that a student’s level of subsequent institutional commitment is positively related to a student’s perception of the institution’s commitment to students, a student’s commitment to the college or university, the greater is his or her likelihood of persistence in that college or university. Braxton, J. M., Milem, J. F., & Sullivan, A. S. (2000). The influence of active learning on the college student departure process: Toward a revision of Tinto's theory. Journal of higher education, 569-590. 718 first-time, full-time firstyear students at a highly selective, private research I university— 51% female and 84% Caucasian. To estimate the influence of such forms of active learning as class discussions, knowledge level examination questions, group work, and higher order thinking activities on social integration, subsequent institutional commitment, and student departure decisions. Burbach, M. E., Matkin, G. S., & Fritz, S. M. (2004). Teaching Critical Thinking in an Introductory Leadership Course Utilizing Active Learning Strategies: A Confirmatory Study. College Student Journal, 38(3), 482. 80 students, 19 years of age or older, enrolled in six sections of an introductory leadership course taught by three instructors at a Midwestern university The purpose of this study was to confirm that an introductory leadership course that integrates a number of active learning techniques increases critical thinking. Used the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking high school grades, and a student’s initial level of institutional commitment. A student’s level of subsequent institutional commitment was found to be positively related to retention. Other findings included that a one-unit increase in a student’s subsequent institutional commitment raises the odds of that student’s remaining enrolled in the institution the following semester by 3.08 times. Two of the four indicators of active learning wield statistically significant influences on social integration (and less departure/drop-out). Class discussions (beta = 0.21, p < 0.0001) and higher order thinking activities (beta = 0.05, p < 0.0001) positively influence social integration. However, group work and knowledge-level exam questions fail to exert a statistically reliable effect on social integration. A paired-samples t test was conducted to evaluate whether students' critical thinking skills increased by the end of the semester. Two subtest scores (Deduction and Interpretation) and the Total Critical Thinking test score were significantly higher (p (.05) at the end of the course. Appraisal as a preand post-test. Chrispeels, H. E., Klosterman, M. L., Martin, J. B., Lundy, S. R., Watkins, J. M., Gibson, C. L., & Muday, G. K. (2014). Undergraduates Achieve Learning Gains in Plant Genetics through Peer Teaching of Secondary Students. CBELife Sciences Education, 13(4), 641-652. Biology 101 for nonmajors course at a private liberal arts college. 64 participated the first year, 54 the second year. The majority of participants were freshman across the two years. DeNeve, K. M., & Heppner, M. J. (1997). Role play simulations: The assessment of an active learning technique and comparisons with traditional lectures. Innovative 29 undergraduat e students (n = 21 female) enrolled in a three-credit hour industrial psychology While acknowledging the study limitation regarding the inability to control external variables, this course, which utilized active learning strategies did improve critical thinking skills. Although it was not possible to determine which of the active learning strategies had the greatest impact on improving students' critical thinking skills, the course did contain several key strategies that research has linked to critical thinking skill improvement (journal writing, service learning, small groups, scenarios, case study, and questioning). Researchers Student tests showed believed that SLP that, across the board (service learning (both the tutors for high programs) as an school and those for active learning middle school), students tool will positively learned the materials that affect students’ they knew they would be understanding of teaching at a higher level genetics and other than the materials that concepts. SLP, in they were not teaching. this case, involved The level of students that students learning the tutors were serving materials in order (high school vs middle to act as tutors for school) did not appear to high school or have an effect on test middle school scores. science students. Researchers For the first prediction (a), predicted that: (a) students rated the rolestudents would play scenarios as a 4.4 out react positively to of 5 point scale on the technique interesting/exciting and 7 during class and at on a 9 point scale on the 8-month recommending it to be follow-up used in other courses. Higher Education, 21(3), 231-246. course at a large Midwestern university. Eighty-three percent of the students were seniors at the time of enrollment. interview, (b) students would report that the role play simulations were more applicable than traditional lectures for jobs students held at the time of the follow-up interview, (c) students would report that the traditional lectures were more applicable than the role play simulations for other college course work, and (d) at the 8-month follow-up interview students would recall more information from a specific role play simulation than from a specific lecture that focused on one general topic covered by both teaching methods. Dori, Y. J., & Belcher, J. (2005). How does technologyenabled active learning affect undergraduate students' understanding of electromagnetism concepts?.The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2), 243-279. Fall 2001 (experimental) , Spring 2002 (control), and Spring 2003 (experimental) semesters. 176 students in 2001. 121 students in Following the social constructivist guidelines and employing educational technology, the objectives of the Project are to: 1. Transform the For the second prediction (b), 91% gave positive comments. As expected, the difference between the mean number of positive and negative comments was statistically significant, t(23) = 3.83, p < .001, indicating that students reported more positive comments (M = 2.13 positive comments) than negative comments (M = .60 negative comments). Prediction c was supported, t(20) = 2.29, p < .05, with the mean response being 4.9 for the role play simulations and 5.6 for the lecture material. The mean recall of information from the role play simulation was .74 (1 = recall some information correctly) and the mean recall for the lecture was .24 (0 = recall no information correctly). This predicted difference in mean recall of material was marginally significant, t(23) = 1.93, p = .07, indicating students tended to recall more information from the role play simulation. Through observations, researchers found that the social activities involved in the workshop design really had an impact on students as they were more actively involved and affective. Analyzing the conversations, 2002 (control). 514 students in 2003. way physics is taught at large enrollment physics classes at MIT. 2. Decrease failure rates in these courses. 3. Create an engaging and technologically enabled active learning environment. 4. Move away from a passive lecture/recitation format. 5. Increase students' conceptual and analytical understanding of the nature and dynamics of electromagnetic fields and phenomena. 6. Foster students' visualization skills. he research goals are: 1. In the social domain, to characterize student interactions while studying in small groups in the TEAL project; 2. In the cognitive domain, to assess students' conceptual change as a result of studying electromagnetism in the TEAL project; and 3. In the affective domain, to researchers found that students' discourse could be categorized into four types: technical, sensory, affective, and cognitive. In addition, the failure rates in the two experimental groups were less than 5% in the smalland large-scale experimental groups, respectively, compared with 13% in the traditional control group. All three levels of students in (low scoring, average, and high scoring) scored better on post-tests in the workshop groups. Low achieving students showed the highest gains. The TEAL project was well received in the small-scale implementation and with reservations in the 2003 large-scale implementation. In the small-scale about 70% said they would recommend the TEAL course to their peers, although in the large-scale the corresponding percentage was 54%. Ebert-May, D., Brewer, C., & Allred, S. (1997). Innovation in large lectures: Teaching for active learning. Bioscience, 601-607. 1st Case: 559 students in four lecture sections of approximately 140 students each. 2nd Case: 450 students in an introduction to biology lecture course. analyze students' attitudes towards the TEAL learning environment, and to study their preferences regarding the combination of various teaching methods. Which approach is more effective with students for self-efficacy and scores, traditional or an activelearning model based on the learning cycle of instruction? Does personalization make a difference? A comparison of mean scores from the selfefficacy instrument indicated that student confidence in doing science, in analyzing data, and in explaining biology to other students was higher in the experimental lectures (N = 283, DF = 3, 274, P< 0.05). Moreover, students in the experimental lectures scored higher on the process questions from the NABT exam (N = 341, DF= 1, 336, P < 0.005). Interestingly, student scores on the content portion of the NABT exam in the experimental lectures were not significantly different from scores of students in the traditional lectures, which suggests that allocating time to cooperative learning activities at the expense of delivering more content did not harm student learning or reduce knowledge acquisition. When asked to describe the learning environment in their lectures, students in the experimental lectures usually characterized the classroom environment as friendly, nonthreatening, fun, and dynamic. In addition, they reported a sense of belonging and camaraderie because they regularly interacted with peers and learned from each other. Qualitative observations indicated that attendance was higher in the experimental classrooms at NAU and UM than in lectures taught in the traditional format. Student desire to participate was also high. Instead of fewer than ten students raising hands to answer a question, scores of students regularly volunteered to provide answers. Fayombo, G. A. (2014). Enhancing Learning Outcomes in Psychology through Active Learning Strategies in Classroom and Online Learning Environments.Internation al Journal of Learning and Development, 4(4), Pages114. 158 out of 189 Psychology undergraduat e students who offered Learning Theory and Practice Course at The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados. Their age ranged between 1860 years (Mean age 39.0years, SD = 1.73). There were 59 males 1) Are the learning outcomes satisfactorily achieved in this course? 2) Did the students participate in the lectures and online activities? 3) What is the profile of students’ ratings on active learning strategies utilized in the classroom and online? 4) Are there significant relationships among the active learning strategies utilized in the classroom (video and role play), 1) The SLOs were achieved among this sample in both classroom and online environments with the mean score of 30.44 (40 possible). 2) Percentage breakdown as follows: 85% participation in role-play, 98% watched videos, 89% participated in online discussions, 83% took part in glossary activities, 99% participated in group presentations. Students did participate actively in the classroom and online activities. 3) The majority of the students agreed that all the strategies enhanced their learning thus: video 100%; role play 93%; Georgiou, H., & Sharma, M. D. (2015). Does using active learning in thermodynamics lectures improve students’ conceptual understanding and 99 females. those utilized online (discussion forum and glossary activities) and the student learning outcomes (SLOs)? 5) Will active learning strategies predict SLOs? 6) What are the relative contributions of the active learning strategies to SLOs? 7) What are the relative contributions of the active learning strategies utilized in the classroom and online to SLOs? Appx. 500 students enrolled in a regular physics course at an Australian 1. Is the conceptual understanding of students who engage in ILDs (Interactive discussion forum 90% and glossary activity 83%. 4) There were statistically significant positive correlations among the active learning strategies utilized in the classroom (video and role play), those utilized online (discussion forum and glossary activities) and the student learning outcomes. 5) Active learning strategies (classroom and online) significantly accounted for 11% (Rsquare =0.112); (F (4,153) = 4.84, p < .05) of the variance in student learning outcomes. Therefore, the active learning strategies significantly predicted student learning outcomes among some UWI psychology undergraduate students in Barbados. 6) Surprisingly, only video clips had significant relative contribution, (β= 0.243, p< 0.05), while role play, discussion forum and glossary activity did not. 7) Overall, the classroom strategies contributed more (β= 0.288, p< 0.05) to the variance in SLOs than online strategies (β= 0.047, p> 0.05) and this result was significant. The thermal concepts survey (TCS) was given to prove the first question. First there is an overall improvement exhibited by gains in the range of 0.27– and learning experiences?. European Journal of Physics, 36(1), 015020. university— these students were expected to have completed a physics course in high school. Lecture Demonstrations) as measured by a conceptual survey higher than those who do not engage with ILDs? 2. What do lectures with ILDs look like in comparison to those that do not have ILDs? 3. What are student experiences of ILDs? 0.40, and an average of 0.31 which is considered medium to high when considering existing data. Second, the streams with ILDs exhibit higher gains as indicated by the normalized gain measure and the effect size, d, as calculated from the comparisons between highest and lowest means which is 0.40 and indicates a noteworthy effect. The effect size of 0.40 falls in the medium range which is amongst the best for educational studies in authentic settings. Upon comparing the ILD and non-ILD lectures, the least interactive ILD lecture still had 60% more interactive activities and time than did the most interactive non-ILD lecture. On a Likert scale survey, two thirds of the students were in overall agreement that the ILDs did help them understand specific ideas better. More than 70% of the students are in overall agreement that ILDs support lectures and help in understanding concepts. Some 65% of the students are in overall agreement that ILDs provide opportunities for scientific reasoning while 81% indicated that ILDs were challenging for learning. Of particular note is that 73% of students were in overall Leite, F. N., Júnior, H. A., Hoji, E. S., & Vianna, W. B. (2014). Using problem-based learning (PBL) in technical education. Proceedings of ALE 2014 16 students in a technical course in a Brazilian high school. Will instituting a more active approach to this technical course via PBL help students attitudes? Will grades increase and failures and dropouts decrease? Haidet, P., Morgan, R. O., O'Malley, K., Moran, B. J., & Richards, B. F. (2004). A controlled trial of active versus passive learning strategies in a large group setting. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 9(1), 15-27. Family and Community Medicine, Internal Medicine, and Pediatrics residents at two academic medical institutions To compare the effects of active and didactic teaching strategies on learning and process-oriented outcomes. Keeler, C. M., & Steinhorst, R. K. (1995). Using small groups to promote active 3 courses of statistics, using the Investigate whether a cooperatively agreement that the predictions helped realize their misconceptions. Student feedback was slightly mixed (some thought that the teacher just didn’t want to work) but over 60% voiced that the PBL approach helped them be more actively engaged with the content. In comparing grades and failure/dropouts from the year previous (before the PBL designs were implemented), the class grade average went from 4.9 in 2012 to 7.5 in 2013. Dropouts were cut in half from 4 in 2012 to 2 in 2013. Failures went down from 3 in 2012 to 1 in 2013. Both teaching methods led to improvements in residents’ scores on both knowledge and attitude assessments. The amount of improvement was not statistically different between groups. Residents in the active learning session perceived themselves, and were observed to be, more engaged with the session content and each other than residents in the didactic session. Residents in the didactic session perceived greater educational value from the session compared to residents in the active session In the traditional course, there were 5 As, 11 Bs, 22 Cs, 26 Ds, 3 earned Fs, 9 Fs learning in the introductory statistics course: A report from the field. Journal of Statistics Education, 3(2), 1-8. same text and materials, 1 traditional and two were collaborative. structured course where students work in groups would produce higher grades and result in greater retention of students in the course than the traditionally structured instructional method. Kvam, P. H. (2000). The effect of active learning methods on student retention in engineering statistics. The American Statistician, 54(2), 136140. Two classes of students participated in the study-one class was taught using traditional lecture-based learning, and the other class stressed group projects and cooperative learning-based method. 23 from the traditional course participated in the study while 15 of the cooperative class participated. Researchers compared the effects of cooperative learning methods to the effects of traditional learning methods in teaching a calculus-based, undergraduate engineering statistics course, with particular attention paid to the long-term ability to retain the material learned in class. due to not attending, 3 incompletes, and 21 withdrawals. In the first collaborative course, there were 11 As, 30 Bs, 43 Cs, 2 Ds, 2 earned Fs, 5 Fs due to not attending, 2 incompletes, and 5 withdrawals. In the second collaborative course, there were 20 As, 30 Bs, 28 Cs, 8 Ds, 2 earned Fs, 5 Fs due to not attending, no incompletes, and 7 withdrawals. Not only did a larger percentage of students successfully complete the course under cooperative learning, but those who completed the course earned higher marks. Students who scored well on the first test exhibited equal abilities in remembering the course material for the second exam, no matter what method of teaching was applied. Students who fared worse on the first exam appear to retain concepts better if they were taught using activelearning methods. The researcher admitted, however, that the effects were so small that it made the findings inconclusive and a larger population was needed. Martyn, M. (2007). Clickers in the classroom: An active learning approach.Educause quarterly, 30(2), 71. 2 classes that used clickers (n=45) and 2 classes that used class discussion (n=47) of an introductory computer information systems course at a small midwestern liberal arts college. McCarthy, J. P., & Anderson, L. Introductory (2000). Active learning course techniques versus covering traditional teaching styles: United States two experiments from history up to history and political 1865--large science.Innovative Higher course that Education, 24(4), 279-294. divided into eight discussion sections—and two honors level "Introduction to American Government" classes—one formed the experimental group, the other, the control group. Miller, C. J., & Metz, M. J. (2014). A comparison of professional-level faculty and student perceptions of active learning: its 9 faculty members of the Department of Physiology Are students’ grades and perceptions improved by using an active learning clicker approach to teaching? For the post-test scores, no significant difference was found between the two groups. For the perception survey, although no significant difference was found, the clicker group consistently scored their classes higher. Do traditional methods, such as lectures or teacher-centered discussion sections, achieve this better than more stimulating, student-centered classroom activities? Conversely, can active learning techniques help students acquire a level of knowledge equivalent to or greater than that acquired through the traditional formats while they stimulate student interest and help them develop critical thinking skills? Are there differences in the way faculty and students view active learning? The difference in the mean performance of the experimental group in political science was +0.8, while that in history was +1.0. These results suggest that the groups exposed to the active learning activities outperformed those taught by traditional methods. In the case of the political science classes, a one-unit increase in the independent variable (moving from control to experimental group) increased the test score by .85 of a point on average. For the history students, the impact was close to a whole point on a ten-point scale For faculty members who had actually used active learning strategies, its effectiveness was scored at 4.57 (out of 5) current use, effectiveness, and barriers. Advances in physiology education, 38(3), 246-252. and Biophysics at the University of Louisville 116 students from the same department Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). Engaging students in active learning: The case for personalized multimedia messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 724. Experiment 1: 34 college students recruited from the psychology subject pool at the University of California, To what extent can the selfreferencing of instructional materials help students' learning, in retention and problem-solving transfer? compared to 3.88 by those who had only observed it being used. Even though active learning strategies were seen to be better, across the board, professors still used the traditional lecture format primarily. A high percentage of both faculty members (44% of respondents) and students (91%) indicated that faculty members were accustomed to lecture-based methods. Both groups reported that there could be major issues with the amount of class time available to use active learning (faculty members: 89% and students: 41%), the time needed to develop the materials (faculty members: 33% and students: 29%), and a lack of training (faculty members: 22% and students: 53%). Students also felt that major barriers to the adoption of active learning could include a lack of faculty awareness (35%) or that faculty members did not see the strategy as a productive use of class time (45%). Experiment 1: Students in the P group generated significantly more conceptual creative solutions on the transfer test than did students in the N group, 5.87 compared to 4.31 (on a 10 point test). Students in the Santa Barbara. . There were 17 participants in the personalizedspeech group and 17 participants in the neutralspeech group. Experiment 2: 44 college students recruited from the psychology subject pool at the University of California, Santa Barbara. There were 22 participants in the personalizedtext (P) group and 22 participants in the neutraltext (N) group. Experiment 3: 39 college students from the psychology subject pool at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Eighteen participants served in the personalized (P) group, and 21 participants served in the nonpersonalized (N) group. Researchers believe that their approach predicts that students who learn a computerbased lesson by means of a personalized message will remember more of the factual information and solve problems better than students who learn by means of neutral messages. P group did not recall significantly more conceptual idea units on the retention test than did students in the N group, 5.62 compared to 5.44 (on an 8 point test) . The effect sizes were 1.00 for transfer and 0.15 for retention. Although both groups remembered equivalent amounts of the verbal explanation for lightning, participants in the P group were better able than those in the N group to use the information to solve novel problems. Experiment 2: Students in the P group generated significantly more conceptual creative solutions on the transfer test than did students in the N group, 5.09 compared to 2.36. Students in the P group did not recall significantly more conceptual idea units on the retention test than did students in the N group, 5.73 compared to 5.41. Experiment 3: On transfer, P students scored higher (41.89) than N students (28.62) on a 60 point test; retention--8.17 compared to 6.67 on a 9 point test; and slightly higher on program rating--32.67 compared to 31.10 on a 50 point survey. Experiment 4: Personalized scored higher than nonpersonalized 46.05 Experiment 4: 42 college students from the psychology subject pool at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Twenty-one participants served in the personalized text (P) group, and 21 participants served in the nonpersonalized text (N) group. Experiment 5: 43 college students from the psychology subject pool at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Twenty-two participants served in the personalized narration (P) group, and 21 participants served in the nonpersonalized narration (N) group. Rao, S. P., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2001). 252 students Active learning of that were respiratory physiology taught using improves performance on active-learning respiratory physiology strategies with examinations. Advances in a class of 84 students that compared to 38.48 on a 60 point transfer test; slightly higher on retention 8.19 compared to 7.43 on a 9 point scale; and slightly better on program rating--32.81 compared to 28.81. Experiment 5: P group scored higher on transfer-40.55 compared to 31.86 on a 60 point test; slightly higher on retention--8.05 compared to 7.19 on a 9 point test and 31.46 compared to 29.41 on a 50 point program evaluation. Will active learning strategies (peer instruction, role play, interactive games, debate, etc) The mean percentage of correct answers of the traditional group (n=84) on the traditional (graduate) respiratory physiology examination and the traditional Physiology Education, 25(2), 55-61. Reinhardt, C. H., & Rosen, E. N. (2012). How much structuring is beneficial with regard to examination scores? A prospective study of three forms of active learning. Advances in physiology education, 36(3), 207-212. were taught using the traditional lecture format in a respiratory physiology course. improve students’ scores on exams? Seventy-five students of three physiology courses (mean age: 20.1 1.3 yr) at further education in college (Bonn, Germany), grouped via low, mid, and Comparison of the relative effectiveness of three different active learning forms (collaborative learning, cooperative learning, and active lecture) on achievement in volunteer group (n=38) on the respiratory physiology examination developed for the active-learning group was 60 +/- 1.5 and 61 +/- 2.2, respectively. There was no significant difference on the performance of the traditional group on the traditional (graduate) respiratory physiology examination and the traditional volunteer group on the active (medical) respiratory physiology examination. These results suggest that the traditional (graduate) and active (medical) respiratory physiology examinations were similar in content and difficulty. However, the mean percentage of correct answers for the active learning group (n= 252) on the active (medical) respiratory physiology examination was 86 +/1.0. The active-learning students performed significantly better (P < 0.05) than the traditional group students on the same examination. The main findings regarding the primary outcome parameter were a persistent significant difference with regard to exam scores between the active lecture group compared with the collaborative group in part 1 (P = 0.009) and part 2 (P = 0.05), respectively. Cooperative learning high entry test scores, then randomly assigned to three groups— active lecture, cooperative learning, and collaborative learning. Ruckert, E., McDonald, P., Birkmeier, M., Walker, B., Cotton, L., Lyons, L., ... & Plack, M. (2014). Using Technology to Promote Active and Social Learning Experiences in Health Professions Education. Online Learning: Official Journal Physical Therapy Management of the Aging Adult course in the Doctor of Physical Therapy Program (PT) at George Washington physiology at a further education college. The primary outcome parameter was cognitive achievement with regard to a written class test. The second outcome parameter, which applied only to the collaborative and cooperative groups, was the quality of their poster presentations. The researchers’ hypothesis was that if we respect the standards of collaborative and cooperative learning as described in the literature and provide sufficient learning time, cooperative and especially collaborative learners should produce the highest exam scores. Researchers wanted to see if the following exemplars made a positive impact on students’ selfefficacy about what they learned. Exemplar #1: Using Technology groups scored higher than collaborative groups: in part 1, cooperative learning groups obtained significantly better results (P = 0.05); in part 2, cooperative learning groups attained much better results but did not differ significantly (P = 0.056). Concerning high taxonomy tasks (synthesis and evaluation), the cooperative and collaborative groups tended to have better results; however, the differences did not reach significance. Exemplar #1: 94% agreed with “Priming activities helped me learn the course material.” 74% agreed with “The use of technology helped increase my level of engagement with this course.” 71% agreed with “The quality of this course of the Online Learning Consortium, 18(4). University was used for Exemplar #1 (34 students). Clinical Skills 2 course in the Physician Assistant (PA) Program at GW was used for Exemplar #2 (66 students). Health, Justice, and Society (HSJ) course within the PA Program at GW was used for Exemplar #3 (67 students). Clinical Conference IV course within the PT Program at GW was used for Exemplar #4 (34 students) to Create “Priming Activities” to Prepare Learners for In-class Engagement Exemplar #2: Using Videos to Facilitate Clinical Decision Making and Reflection Exemplar #3: Using VoiceThread® to Promote Critical Thinking, Collaboration, and Higher Levels of Learning Exemplar #4: Using Twitter® to Enhance Reflection was improved by the use of technology.” Exemplar #2: 74% agreed with “Video recording and evaluating my oral case presentation was a positive learning experience.” 69% agreed with “[The OCP] activity promoted the development of my oral presentation skills.” Exemplar #3: 9% agreed with “VoiceThread® assignments helped me learn the course content.” 21% agreed with “OL discussions encouraged me to examine my thoughts, beliefs, or feelings regarding course topics.” 52% agreed with “FTF discussions encouraged me to examine my thoughts, beliefs, and or feelings regarding course topics.” 26% agreed with “OL journal entries encouraged me to examine my thoughts, beliefs, or feelings regarding course topics.” (Note: the majority of the percentage of votes for the Exemplar #3 technology fell mid-range) Exemplar #4: 70% responded in agreement that the objectives of the assignment were met, specific to reflection, professional engagement and discussion with peers, and development of professional use of social media. Sand-Jecklin, K. (2007). The impact of active/cooperative instruction on beginning nursing student learning strategy preference. Nurse education today,27(5), 474-480. 87 beginning level baccalaureate nursing students who were enrolled in the initial nursing fundamentals course at a Large Mid-Atlantic University, randomly divided into two classes— one with a traditional approach and one with an active learning approach. 1. What is the impact of incorporation of active and cooperative instruction strategies on student preference for instructional methodology? 2. What is the impact of incorporation of active and cooperative instruction strategies on student use of learning strategies in the classroom and in out-of-class studying. Sivan, A., Leung, R. W., Woon, C. C., & Kember, D. (2000). An implementation of active learning and its effect on the quality of student learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 37(4), 381389. Three courses of the Department of Hotel and Tourism Management at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University: Hotel Human Environment; Human Resources Management; Was is the effectiveness of the active learning strategies being integrated into the HKPU’s courses? Although both the traditional instruction and active instruction student groups reported an overall preference for passive instructional methods, instructor demonstration/applicatio n, and interaction/discussion were ranked above lecture in terms of importance to learning by both groups. The traditional instruction group had a notably lower preference for active teaching strategies [t (df 44) = 3.32, p = .002] and a higher preference for passive teaching strategies [t (df 44) = _2.49, p = .017] at semester end. The active instruction group had a higher preference for active strategies [t (df 91) = _2.92, p = .004] Both groups preferred traditional strategies in out-of-class studying. Overwhelmingly, students preferred the active seminar sessions over lectures for independence, application, carrier, effectiveness (only the Economics for Tourism group ranked lecture higher), and interest. For understanding and remembering, votes were split between the lecture and seminar types. and Economics. Udovic, D., Morris, D., Dickman, A., Postlethwait, J., & Wetherwax, P. (2002). Workshop biology: demonstrating the effectiveness of active learning in an introductory biology course. Bioscience, 52(3), 272-281. Three years of biology survey courses at The University of Oregon. In the first year, only two sections were used for the workshop approach but this evolved over the next few years to include more and more sections. Wilke, R. R. (2003). The effect of active learning on student characteristics in a human physiology course for 141 students taking a human physiology The more supportive environment of the workshop course and the focus on issues would improve students’ attitudes towards science and science courses more than comparison versions of the course. For conceptual learning, workshop students would do as well as students in the comparison group, despite coverage of more content in the traditional course. Researchers wanted to find out if there would be a significant For seminar activities, students ranked the hotel simulation as the most valuable, followed by discussion/debate, case study/problem solving, presentation, role play and games, etc. Video was ranked the lowest out of the given activities. Study Process Questionnaire changes from pre- to post-testing shows, across the board, a rising of “deep approach” meaning that students found their learning deeply meaningful. Researchers found that inquiry-based instruction helped students understand fundamentals better as well as enabled better problem-solving using new concepts. However, student views about the process were complex. While workshop students tended to value their experiences more highly, they were also more critical. (Some students balked at the steeper work load for the same amount of credit.) The first year, students in the workshop course scored consistently higher on the post-test than that of the comparison course. Students in the treatment group generally reported a greater appreciation of the course and thought nonmajors. Advances in physiology education,27(4), 207-223. course, divided into 71 for the control group and 70 for the treatment group. Wolf, A., Liachovitzky, C., & Abdullahi, A. (2014). Active Learning Improves Student Performance in a Respiratory Physiology Lab. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 4(1), p19. The study was conducted at Bronx Community College, a campus of the City University of New York, over the course of six semesters between 2009 and 2012, comprising 8 sections of a secondsemester Anatomy & Physiology course. Four “control” sections (n=76 students) were taught using the standard, previously developed curriculum. Four “test” sections (n=73 difference in test results between classes taught using traditional lecture methods and those taught using active learning methods. The same text and tests were used across the courses. They also wanted to see how students felt about their own abilities. The study had three goals: First, researchers compared the performance of students in the modified labs with students in previous sections. Second, within sections using the modified lab researchers compared performance on concepts from the modified lab with concepts from the rest of the semester. Finally, after the completion of the lab researchers asked students about their perceptions of learning in the modified labs. that the subject matter was more approachable than those who were in the traditional lecture course. The 2x2 factorial analysis determined that the treatment groups performed significantly better on the comprehensive physiology content exam than the control groups (F 5.07, P 0.026) On the midterm exam overall, there was a slight, though statistically insignificant, difference between the test and control sections (74.6±13.7% Test vs. 71.8±13.5% Control, p>0.05). This result is unsurprising because of the cumulative nature of the exam (80% of what was covered on the exam had not been part of the modified content). On questions relating to the relationship between pressure, volume and airflow, the test sections (74.3±12.5%) performed better than the control sections (66.3±9.6%), though the difference was not significant (p=0.09). However, on questions relating to the measurement and identification of respiratory volumes (Test: 77.9±9.2%, Control: 69.5±9.7%, p<0.05) and on students) were taught using a modified curriculum (mainly around the respiratory physiology lab), designed to incorporate principles of active learning, using studentgenerated data. the hallmarks of restrictive and obstructive diseases (Test: 77.5±12.7%, Control: 57.2±12.2%, p<0.005), the test sections performed significantly better than the control sections. When data of all four semesters are combined, students performed better on the spirometry concepts than on other concepts assessed on the midterm. (76.5±4.3% vs. 70.9±1.5%, p<0.05) When asked about whether the lab modifications improved understanding of respiratory physiology concepts (Table 4), more than 75% responded favorably (either Strongly Agree or Agree) for all of the concept groups, except for obstructive vs. restrictive diseases (69.2%) and the effect of obstructive diseases on pulmonary function (69.1%). Likewise, responses were generally favorable (more than 75% responding Strongly Agree or Agree) for questions regarding the laboratory experience (e.g., working in groups, interacting with the data acquisition system and computer, etc.). 60.3% responded that the exercises increased their interest in respiratory physiology. Finally, on a summative evaluation, whether students preferred labs Yoder, J. D., & Hochevar, C. M. (2005). Encouraging active learning can improve students' performance on examinations. Teaching of Psychology,32(2), 91-95. Participants were 45 students in 2001, 37 in 2002, and 38 in 2003 enrolled in a 400-level undergraduat e psychology of women class at a large, public university Researchers wanted to see if active learning activities in the classroom would translate to higher scores on exams. that use the technology versus those that do not, 76.5% responded favorably. Over three years of the same class using the same text and tests and taught by the same teacher, the percentage of materials using active learning techniques was gradually increased—13% for the first year, 20% for the second and 27% for the third. Both within a class and between classes, classes scored higher and less variably on items testing materials presented via active learning compared to lecture, autonomous readings, or video without discussion coverage.