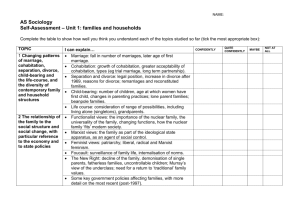

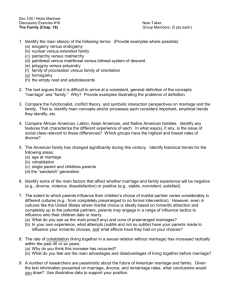

us 2010 discover america in a new century

advertisement