by Neil A.R. Prashad Bachelor of Environmental Studies

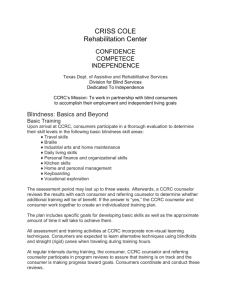

advertisement