ANALYSIS OF HOUSING-RELATED MOVES BETWEEN Florian Frhr.Treusch von Buttlar-Brandenfels

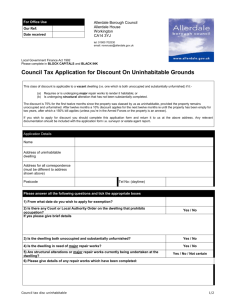

advertisement