Leaders in a Global Economy Families Families and Work Institute

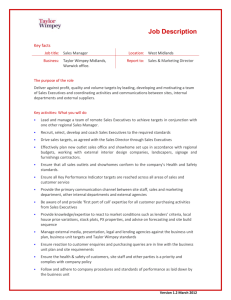

advertisement