Cleaning Cooperatively: An analysis of the ... Virginia L. Doellgast By

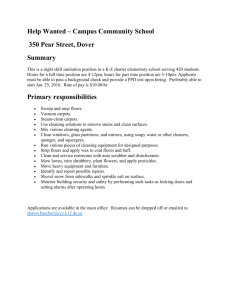

advertisement