Corpus Christi, June 10, 2012

advertisement

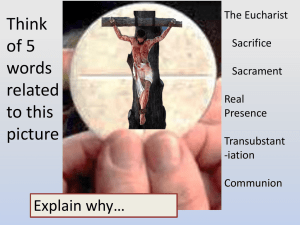

Corpus Christi, June 10, 2012 St.Ignatius Church. Fr. Joseph T. Nolan The title of today’s feast, Corpus Christi, obviously means the body of Christ. But what is that body? The consecrated host, yes. The bread becomes Christ’s body. The church has never pretended it could adequately explain how this is so, but the doctrine has never been less than this: through the invocation of the Holy Spirit and the priest saying the words of consecration, the bread becomes the real sacramental body of Christ, his real presence to the communicant who receives him with faith. With the help of Thomas Aquinas we have tried to explain this, apart from faith, with theories like transubstantiation, the accidents or appearances remaining and the substance changing. But now we look for a new explanation, since physicists have been telling us since 1970 that there are no such things as substance and accidents. This should not cause dismay; there is always a failure of language when dealing with the deepest mysteries, and with God most of all. The complaint is justified that says: for too long more attention was paid to what happened to the bread in the eucharistic rite than what happened, or should be happening, to the people. We are consecrated, too. Our baptism means that we, too, are members of that body. To repeat the words of our greatest dignity: we are the body of Christ. We say "Amen" at the moment of Communion. We should indeed say it; it's an affirmation, a sign of our willingness to become even more a member of that body, striving in small and sometimes large ways to love and serve as Jesus did. To be his presence in the world. Many words we use in worship, as well as gestures like breaking the bread and holding out the cup, are symbols or metaphors full of meaning. God uses them as instruments of grace, to let truth lay hold of us in different ways as we have need, or according to our state of life. Take those words from the heart of the Mass, "this is my body, given for you." We associate them with Christ. Of course. It is Christ on the cross. We could also associate them with Mary, the woman who gave him life. With hands on the womb that bore him, the breasts that nursed him, she is uniquely entitled to say to her son, "This is my body, given for you." I recall one special occasion when I held another Mary in my arms. Perhaps I should make it plain that she was all of eight pounds and four days old! I was rejoicing with her parents at whose marriage I had officiated a year before. I looked with amazement at Lise, this lovely person who gave of her own flesh and blood to create new life. Every parent to every child can say: "This is my body, given for you." A martyr could say those words to God. Oscar Romero, at the altar in the city named for the Savior, knowing, even as Jesus knew, that the violence would destroy him. A couple who marry could say those words. Here is the heart of the marriage vow: "This is my body, given for you. This is my life, now shared with you." A man or woman, most of us anyway, spend a life in labor through the body. Not just with muscles but with brains. We grow weary and fatigued within this house of flesh. But we work to do good work, not just to make money but to continue God's act of creation, a vocation to which all of us are called. Rising to a new day, there is meaning in those words from the servant of God--you or me-- "this is my body, this is my life today--given for you." And also for the life of the world. And consider this: when our earthly life is over, in a Catholic funeral the body is brought before the altar. If it is only ashes, they too are brought here. The body belongs in this holy place (don’t be satisfied with a service at the funeral home). In this flesh a human life took form, reached out, touched and loved. In this body a man or woman laughed, played, wept and worshiped. Labored, suffered, died. How fitting at the Mass of Resurrection that we join this life to Christ's sacrifice and say, “This is my body, given for you.” It's all one body. Wordsworth wrote a line he later changed; he said, "I saw one life, and felt that it was joy." There is one life, and one joy--it is all God's, and it is shared with us. And there is one body. It is Christ's. Corpus Christi. For centuries this day called forth a splendor of song, procession, incense, and familiar hymns, all in honor of the Blessed Sacrament. This should not be lost. But there is in the church a new emphasis on the eucharist which sees the presence of Christ in the bread, yes, but in you, and you, and you--in all of us. We owe a profound reverence to each other, a humble and loving service to each other. This new emphasis is one reason the communion has become, for most of us, a completion of the Mass, food for the journey, not a reward for being good. I suggest this is what the Lord had in mind when he said, "This is my body, given for you." If the body of Christ is a daily bread, is it for everyone? If you are speaking of the non-Christian or non-believer, that's a difficult question. Meaning or belief and some quality of faith always should enter in. Let me put it this way: we do not feel right barring anyone from the sacrament. Some would argue that this sacrament, as well as penance, is a ritual that signifies healing, becoming whole, and it is precisely in our brokenness that we need it even more. We need to know that we belong to One who is stronger than us, and who loves us unfailingly, despite our failures. . Communion, we said, is intended to be a daily bread--strength for the journey. So is the word of God, that other bread by which we live. And both word and sacrament are the church's method of assuring us that we do not walk alone, nor without a script to give hope and meaning to our lives. Read again – better yet, memorize and meditate-- that incomparable passage in Luke, the journey to Emmaus. The travelers are us, and the hidden stranger is Jesus, who explains the scriptures to them. And you know how it ends; “they knew him in the breaking of the bread.” So do we.