i!»B DUPL MIT LIBRARIES

advertisement

MIT LIBRARIES

DUPL

i!»B

DEWEY

5

5

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

THE QUALITY OF LABOR RELATIONS

AND

UNEMPLOYMENT

Olivier Blanchard

Thomas Philippon

Working Paper 04-25

June 15,2004

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 02142

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This

http://ssrn.com/abstract=559203

ASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

DEC

7 2004

LIBRARIES

The Quality

of Labor Relations and

Unemployment

Olivier Blanchard

June

15,

and Thomas Philippon*

2004

Abstract

In countries where wages are primarily set by collective bargaining, the

effects

on unemployment of changes

crucially

in the

economic environment depend

on the speed of learning of unions.

This speed of learning

is

likely to

depend

dialogue that unions have with firms, on

in turn

on the quality of the

what can more generally be

called

the quality of labor relations.

In this paper,

we examine the

in the evolution of

30 years.

We

role this quality of labor relations has played

unemployment across European countries over the

conclude that

it

has played an important

role:

last

Countries with

worse labor relations have experienced higher unemployment. This conclusion remains even after controlling for labor institutions.

respectively. We thank Emmanuel Farhi for excelWe thank Giuseppe Nicoletti, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, Jim

data. We thank Daron Acemoglu, Roland Benabou, Xavier Gabaix,

MIT and NBER, and NYU-Stern

lent research assistance.

Snyder for help with

Ricardo Caballero, Pierre Fortin, Richard Freeman, Peter Hall, Francis Kramarz, and

Andrei Shlcifer for discussions.

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/qualityoflaborreOOblan

Introduction

1

In countries where wages are primarily set by collective bargaining, the

effects

to

on unemployment of changes

depend

crucially

in the

economic environment are

likely

on the speed of learning of unions.

This speed of learning

is

likely to

depend

in turn

on the quality of the

dialogue that unions have with firms, on what can more generally be called

the quality of labor relations.

we examine

In this paper,

in the evolution of

30 years.

We

We

conclude that

start, in Section 1,

increasing to

11%

reaching a low of

able to

the role this quality of labor relations has played

unemployment across European countries over the

has played an important

it

with a "case study", that of the Netherlands. After

in the early 1980s,

2%

Dutch unemployment turned around,

in the early 2000s.

This turnaround

wage moderation. This wage moderation appears

in turn to the dialogue

mitment to reestablish

last

role.

between unions and

firms,

is

directly trace-

directly traceable

1

and to the unions com-

margins so as to increase capital

sufficient profit

accumulation and employment.

We

then present, in Section

unemployment.

2,

We show how

a simple model of wage determination and

the effects on unemployment of different

changes in the economic environment depend crucially on the perceptions

of unions

We

and

their

speed of learning.

then turn, in Section

3,

to the cross country evidence.

two measures of the quality of labor relations, the

intensity in the 1960s, the other based

We

We

We

construct

based on strike

on surveys of managers

show that countries with worse labor

and longer-lasting unemployment.

first

in the 1990s.

relations have experienced higher

show that the

after controlling for labor market institutions.

effect

remains even

The Netherlands

2

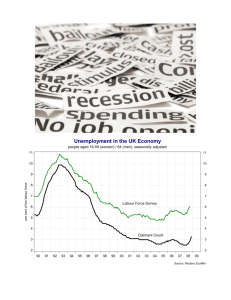

The

evolution of

unemployment

often called the "Dutch

in

11%

1970 to

in the

Netherlands since the early 1980s

unemployment miracle". After increasing from 2%

in 1983, the

steadily to reach a low of

unemployment

2%

rate turned around, decreasing

in 2001. Today,

has increased back to 6%,

it

but most of the increase since 2001 appears to be

The

focus on the

is

1

unemployment

rate

is

cyclical.

not misleading.

It is

sometimes

argued that the increase in employment has come from job sharing, from

an increase

in part-time

employment. This

is

not correct:

The

increase in

part-time employment, which has indeed been substantial, has been more

than matched by an increase

an increase

in the participation rate of

women.

decrease in unemployment hides a high

While

it is

by

in the participation rate, in particular

true that disability rolls are

It is also

number

still

argued that the

of workers on disability.

very high, they have decreased

with unemployment, and thus cannot account

unem-

for the decrease in

ployment.

There

in

is

general agreement that the proximate source of the turnaround

unemployment

is

wage moderation. This can be seen

plots the

unemployment rate and the

wage

more

(or

(log)

wage

precisely the labor cost, as the

wage and non-wage

in

Figure

1,

which

in efficiency units.

The

measure includes both the

benefits) in efficiency units

is

constructed under the

assumption of Harrod neutral technological progress, following Blanchard

[1997];

it

is

normalized to equal zero in 1970-71.

On

a balanced growth

path with constant unemployment, the wage in efficiency units should be

constant. Thus, one can think of decreases in this

wage moderation. As Figure

1

indicates, the

wage measure

wage

as reflecting

in efficiency units

indeed decreased steadily since the early 1980s, standing in 2001 at

its

1970 value; this decrease

1.

Two

[2000].

is

has

83%

of

substantially larger than the decrease of the

useful references are Visser

and Hemerijck

[1997],

and Nickell and Van Ours

same

European Union

variable for the

wage moderation

as a whole. This

has led to an increase in profit, which has led to an increase in capital

accumulation, and an increase in employment over time.

Figure

1.

Unemployment and wage

the

in efficiency units, in

Netherlands, 1970-2002.

There

is

also general

agreement that the start of

this

wage moderation can

be traced to a particular event, the "Wassenaar Accord," signed at the

end of 1982 between unions, business organizations and the government.

At that time, unemployment had increased very

quickly,

and

and

profit

investment rates had collapsed. Unions, explicitly recognizing the need to

reestablish profit margins, agreed to

wage moderation. Despite tensions

along the way, this commitment to wage moderation has remained to this

day.

This short description

it

actually was.

may

give the impression of a process smoother than

The Wassenaar Accord was preceded by

nine failures in the previous nine years.

agreement, with

much

give

and

The Accord

take, including a

nine attempts and

itself

was a complex

commitment by

firms to

consider decreasing working time (at the same wage per hour). Yet,

mains the case that the turnaround

in

wage

setting

happened

it

re-

earlier in

the Netherlands than in other European countries, and observers credit

and

its

it

subsequent follow- through to a long-standing tradition of dialogue

between unions and

firms. Katzenstein [1985] for

example attributes

it

to

"corporatism," which he defines as "an ideology of partnership, expressed

at the national level

flicting objectives

state bureaucracy,

An

(

);

through continuing bargaining between interest groups,

and

political parties."

important question,

ployment,

is

and voluntary and informal coordination of con-

how much

in light of the research

of the decrease in

on the causes of unem-

Dutch unemployment can be

ajey }U8iuAo|dwaun

9

P

Z

8

o

o

o

CNJ

CM

00

G)

CD

4—

05

C\l

o

o

CM

o

i

a:

(D

+j

CD

CD

^

>>

o

N(D "o

^"~

C/)

"D

o

CD

U=

LU

CD

(D

-C

E

>^

o

CD

CD

JC

h•

Y-

CD

E

CD

C

.!?

D

to

D

o

o

o

<

c

CD

§

00

CD

CO

c

CD

CO

CO

CO

D

CO

c/5

+-

•

c

o

c

(D

'o

E

o

^

LU

_c

Q.

E

O) C

L

CD

a

1_

CD

CD

r

Z

*-•

c

(i

_c

TJ

-»—

CD

(D

Q.

C

03

c

o

T™*

c

o

"a

•*—•

c

C

4—

CD

uo

D

CD

T

o

i

CD

t—

C

o

CD

N

o

CD

*-»

CO

TJ

<>

CD

N

ro

E

L_

o

c

o

CD

T

Lsnufi Aouapijjg

in

a6e/v\

CD

O)

CD

attributed directly to this change in union attitudes given labor market

and how much can be attributed to reforms of these labor

institutions,

The question goes beyond

market

institutions.

Nickell

and Van Ours

[2000] for

the scope of this paper (see

an exploration, Schettkat

[2003] for a care-

ful characterization of institutions and institutional change), but one can

make

the following remarks:

The period

since 1982 has seen a

number

Dutch labor

of reforms of the

market. These reforms have however taken place in the late 1980s and the

1990s, thus

some time

after the start of

the decline in unemployment.

rather, they have reduced

wage moderation and the

The reforms have

some

level of social insurance, rather

typically not

start of

been

radical;

of the distortions associated with a given

than decreased that

level.

A

decrease in

replacement rates, and the conditioning of benefits on the acceptance of

"suitable jobs" have decreased the incentives to remain unemployed.

Expe-

rience rating of firms according to their history of worker disabilities have

decreased the incentives for firms and workers to use disability programs

as alternatives to

unemployment. In general, however, the Dutch system

of social insurance remains

EU average, indeed

EU countries — France,

more generous than the

more generous than the average of the four largest

Germany, Spain, and

Italy

—that today have much higher unemployment

than the Netherlands.

3

Shocks, learning, and unemployment

The purpose

of this section

is

to

show that the

effects of

ployment depend very much on whether and how

fast

shocks on unem-

they are perceived

by unions. The model we present makes no claim to generality;

is

to introduce

some

its

goal

of the major shocks which are typically thought to

have been behind movements

in

unemployment

in

Europe over the

last

30

years,

and show how,

crucially

•

in

each case, the response of unemployment depends

on union's perceptions.

Assume an aggregate production

y

where

n

y, k,

=

function of the form:

min(fc, an)

are output, capital,

and employment

captures Harrod neutral technological change.

given by:

7T

y

=

— wn

=

Assume

=

where r

is

a(l

profit rate is

then

w

a

that the supply of capital

k

The

and a

1

k

•

respectively,

is

given by:

+ 0(tt - r))

the user cost faced by firms, and the parameter 6 measures

the response of the supply of capital to net profit

of the user cost.

The presence

of a on the right

—the

hand

profit rate net

side

is

to insure

the existence of a balanced growth path, where capital and output

increase at the

The

first

same

rate.

two assumptions together imply a labor demand schedule

given by:

n

= -: = H-0(7r-r) = l + 0(l---r)

a

•

a

Assume an economy wide

maximizing the wage

bill,

union, acting as a

(1)

monopoly union, and

wn, subject to the perceived labor demand

schedule:

a

Note that we allow union perceptions of

hats, to differ

and

r, all

denoted by

from the actual values of these three parameters.

The assumption

that the union chooses the wage unilaterally, subject

to the perceived labor demand,

ever convenient,

issue, the

8, a,

is

not particularly

realistic. It is

and allows us to avoid an interesting but

nature of bargaining

when

how-

difficult

the two sides (the firms and the

union) differ in their perceptions. Here, only the union's perceptions

matter

•

for the choice of the

The wage implied by

this

wage.

maximization

W= l{

and employment

is

l

is

given by:

' f+

(2)

l)

.

given by equation (1) (firms are assumed to

know

the true parameters).

If

perceptions are correct, employment

is

given by:

n=i±^>

Keeping 8 and

economy

r constant, the

path, where capital, output,

and

real

(3)

follows a balanced growth

wages grow with

a,

and where

employment remains constant.

Now

•

consider three types of shocks.

Suppose there

is

a slowdown in productivity growth, a decrease in

the rate of growth of a, as was indeed the case in Europe starting in

the mid-1970s.

If

perceptions are correct, so 6 remains equal to

with

If

a,

wages adjust

in line

and, as equation (3) indicates, employment remains constant.

however perceptions do not

time,

a,

employment

will

fully adjust, so

be lower

a exceeds o for some

until a converges

back to

a.

Suppose there

•

is

a sharp increase in the real interest rate, as was

indeed the case in the 1980s and early 1990s in most European countries.

Even

ployment

perceptions are correct, so f remains equal to

if

will decrease as

employment.

If

r,

em-

unions prefer to cut both the wage and

perceptions do not adjust however, the wage does

not change, and the decrease in employment will be larger.

Suppose,

•

in 9.

last,

that there

is

an increase

This evolution has been

less

in capital mobility,

studied than the previous two, but

has clearly taken place in Europe over the

quite relevant:

The elimination

of other barriers to capital

an increase

last

30 years, and

may be

of capital controls and the reduction

movements have

surely increased the elas-

So has the widespread process

ticity of capital to its rate of return.

much more

sensitive to

correct, such

an increase

of privatization: Private owners are typically

the rate of return than the state.

Under the assumption that perceptions are

in 9 leads to

ital

an increase

to the profit rate,

in

employment: The higher

and by implication the higher

ployment to the wage, lead the union to moderate

and thus lead to an increase

in

employment.

If

elasticity of capelasticity of

its

perceptions do not

change however, wages do not adjust, and employment

may

decrease. This depends on whether, initially, firms were

itive or negative net profits. If net profits, 1

negative,

In

all

employment

— w/a —

as perceptions

recover and end

up ultimately

and wages

making pos-

adjust, will

moves

out.

employment

higher.

these cases, the specific dynamics of adjustment will depend on the

speed at which unions learn and adjust wages. The speed of learning

to

actually

r were initially

will initially decrease, as capital

Only over time,

em-

wage demands,

depend

in turn

on how easy these changes

in the

component from year to

likely

economic environment

are to identify. Productivity growth, measured, say, by

a large transitory

is

TFP

growth, has

year. It clearly took a while for

8

the slowdown of the

mid 1970s

to be fully perceived (not only by unions,

but by economists and policy makers as

was

largely hidden

Changes

from view by the

in interest rates should

some

well); for

effects of the

two

time, the

oil

slowdown

price increases.

may

be easier to observe, although unions

not fully perceive the implications for investment and ultimately for em-

may

ployment. Increases in capital mobility

some unions

Europe

in

still

speak as

if

also be hard to assess. Indeed,

profits

were largely rents to be ap-

propriated by workers, without implications for employment. While such

rhetoric

past,

may have been

it is

surely not a

appropriate in some parts of the economy in the

good assumption about

capital mobility today.

Formally introducing uncertainty and learning raises a number of conceptual issues. First, firms, under the maintained assumption that they perceive the changes accurately,

ting

may want

to

employment more than implied by the

be

example cut-

strategic, for

static labor

demand

parameters.

We

move

order

may want

to convince unions that the world has changed. Second, unions

to experiment, to

in

the wage in order to learn faster about the relevant

leave both of these issues aside,

and focus on what

us as the main effect of uncertainty and learning, namely that

it

strikes

takes

some

time for unions to learn, and thus to adjust the wage.

So assume that labor demand

not strategic),

is still

given by equation (1) (so firms are

and that unions maximize the expected wage

period (so they have no incentive to experiment

Consider the case where only productivity a

it

is

bill

period by

2

).

stochastic,

and assume that

follows:

log(a t )

=

log(aj)

+ et,

log(a f*)

=

log(a(_i)

+g

In fact, for the case we consider below, namely uncertainty about productivity a,

unions have no incentive to experiment since the signal to noise ratio does not depend

on the wage they set. This is no longer the case when unions are uncertain about the

2.

elasticity of capital supply, 9.

where

normal, and g can take one of two values, g

et is i.i.d.

words, actual productivity

noise.

is

in the

which

will

In

either positive or zero.

is

mid

ductivity growth decreases from g to

at a rate

0.

equal to underlying productivity plus white

Underlying productivity growth

To capture what happened

— g or g =

1970s, suppose that underlying pro-

0.

Unions

will learn

and adjust wages

depend on the tightness of their prior and the standard

deviation of the transitory component. Figure 2 shows such a path, both

for the

wage

in efficiency units

wt/at and for employment (which

mirror image of the wage), based on an

9

—

Figure

2.

subjective probability that

The response

of the path

is

given in the appendix.)

of wages in efficiency units to a decrease

productivity growth.

The main

feature of Figure 2

is

the

hump shaped

in efficiency units, which, given the static labor

a

the

9 equal to 0.98, a standard deviation of the transitory shock of 2%,

and a value of g of 1% (the derivation

in

initial

is

hump shaped

response of the wage

demand

function, implies

response of employment and of unemployment. As pro-

ductivity growth slows down,

productivity growth for

in efficiency units for

wage growth

some time. This

some time,

until

it

also decreases

leads to

but

an increase

still

exceeds

in the

wage

turns around and returns to

its

steady state value. For the parameters we have chosen, this leads to an

increase in wages in efficiency units of about

roughly consistent what

is

5%

at the peak,

an increase

observed in the data at the end of the 1970s for

the European Union as a whole.

Similar dynamics can be derived with respect to the other shocks, be

increase in interest rates, or an increase in capital mobility.

capital mobility, even

may

if it

well also generate a

initial increase,

An

it

an

increase in

ultimately leads to an increase in employment,

hump shape

response of unemployment, with an

followed by a larger decrease later on.

10

1

1

1

'

1

1

a

1

1

1

'c

3

>.

u

c

D

'o

HI

c

si

>.

Ul

0)

o

5

£

5iS

"1

j

-C

1

U

z

>

o

z:

-o

o

a.

/

o

c

J

2

—

•D

jS'

s

o

'-.

s^

^s^

to

o

1—

n

OJ

0)

cC

"v

n

—

*

IS

'

ra

c

c

g

ro

s

13

C

o

Q_

LL

v-

o

5

o

-

T3

c

It

£

;

>.

o

00

/

1

UJ

o

I

.

03

c

o

3

-»^

.

c

/

s

CD

E

,

111

>>

o

/

Q.

E

LU

ac

03

CO

QJ

-

1

1

1

1

\l

1

1

I

1

cn

03

o

CO

c

g

-+-

TO

E

CN

03

t-

3

Learning, the quality of labor relations, and

4

unemployment

What might

lead to different speeds of learning

and adjustment by unions?

Bayesian learning points to differences in the tightness of priors, and the

informativeness of signals.

ogy,

and

generally,

it

points to differences in ideol-

differences in the quality of labor relations:

common economic

firms share a

nomic implications of

is

More

The more unions and

model, or the more they discuss the eco-

different shocks, the faster learning

likely to be.

4.1

Quality of labor relations and unemployment

With

this motivation in

mind, we construct and study the

measures of the quality of labor relations across

•

and adjustment

The

first

for

theoretical

and empirical work on

looking at strike activity

of labor relations

is

example, Hibbs

1960 to 1967

we want

1970,

is

is

The

a simple one: most of the

strikes suggests that the quality

an important determinant of strike activity

[1987].)

The motivation

for

that this predates the increase in

to explain.

The reason

that, in the late 1960s,

is

countries.

a measure of strike intensity, from 1960 to 1967.

is

motivation

for

OECD

two

effects of

for

(see,

choosing the period

unemployment that

stopping in 1967 rather than, say,

many European

countries, especially

France, Germany, and Italy, were affected by social and political unrest, for

Two

reasons largely unrelated to the quality of labor relations.

measures of

OECD

countries.

strike activity are available for the 1960s for

The

first is

most

a measure of days lost in strikes (DL),

the second a measure of workers involved in strikes (WI).

We express

both as ratios to employment.

When

needed,

STRIKE, which we

define

by the maximum of normalized

measure,

we combine them

in

one

11

days

lost

and normalized workers involved:

\ std{DL)

The standard

for using the

are recorded, while

choice,

when

specification

be lower bounds on

variable, this

that, in the 1960s,

were dictatorships,

max

where

all

strikes

two

strike activity.

OECD

countries, Spain

was

illegal.

and Portugal,

We have no other

using this measure, than to drop these two countries

is

that strike activity depends on other

some

of

them observable

unemployment during the period) some

of

them unobserv-

variables than the quality of labor relations,

able.

that not

measure presents two problems. The

strike activity

from the sample. The second

(such as

is

recorded strikes actually happened, so both

all

likely to

As an explanatory

first is

J

deviations are the cross country standard deviations.

The motivation

measures are

std{WI)

,

This implies that using strike activity as a proxy for quality in

a regression entails measurement error.

We

shall return to the issue

below.

The second measure

is

a direct, survey, measure. In 1999, the World

Economic Forum asked the following question

in

to

managers of firms

a large number of countries: "Are labor relations in your firm

cooperative?"

the country

.

The answer was

mean response

labor relations, and denote

it

Clearly, this second variable

than the

tial

first. It

suffers

given on a scale from

as our second

by

is

to

7.

We

use

measure of the quality of

"COOP"

closer to

what we want

to capture

however from an obvious problem of poten-

reverse causality, as perceptions of the quality of labor relations

by firms

ment

in

1999

may

since the 1960s.

well reflect in part the evolution of

(A similar question was asked

unemploy-

in 1993.

This

is

however also quite late in the period, and the 1993 and 1999 measures

are very highly correlated).

12

If

we think

of the quality of labor relations as a stable feature of an econ-

omy, a natural question

The answer

there

is

sion of

on

how

given in Figure

is

OECD

the 18

is

correlated the two measures of quality are.

3,

COOP

which plots

against

countries for which both measures exist.

a strong negative relation between the two (The

COOP

STRIKE

on

is

STRIKE

is

STRIKE,

As can be

R

2

for

seen,

of the regres-

equal to 0.62, the t-statistic on the coefficient

equal to -5.0). This

is

good news

our implicit main-

for

tained hypothesis that the quality of labor relations

a relatively stable

is

characteristic of countries over time.

Figure

We

3.

Cooperation

in

1999 versus Strikes

1960-1967

in

can then turn to the relation between unemployment and the quality

To do

of labor relations over time.

we

so,

divide the period 1965-2002

into decades (more specifically 1965-1974, 1975-1984, 1985-1994,

2002), and for each decade,

uu

where uu

each

t,

is

the

=

at

we

+b

t

regress:

(quality measure^)

mean unemployment

the coefficient at captures the

across countries during the decade.

Table

1.

The

+ en

rate in decade

common

Our

(4)

,

t

in

evolution of

interest

which captures the extent to which differences

explain differences in

and 1995-

is

country

i.

For

unemployment

in the coefficient bj,

in the quality

measure can

unemployment across countries during the decade.

quality of labor relations

and unemployment

rates,

by decade

Basic results are reported in Table

of estimation using the

COOP

results of estimation using the

1.

The

first

regression reports the results

measure. The second regression reports the

STRIKE

measure (Both are normalized by

13

<

-

[2

CM

C/)

-I—

o

c

o

O

un

!_

o

-Q

CO

o

CD

CD

_l

CD

w

"D

0)

C

c

o

o

CD

CO

c

o

-4—

o

c

o

_CD

CD

o

_Q

o

o

0)

ro

E

o

c

_Q

o

CD

o

00

6)

X

LO

l"

0)

L0

CO

~1

1

1

1

5

L

9

AaAjns 6661 'suo!;e|ay joqei

fr

in

1

e

uouejadooQ

Table

1:

Labor relations and unemployment

in 4 decades.

Dependent variable

is

average unemployment over the decade. Three regressions are run for each decade,

with a different

RHS

variable.

Figure 4

(Cooperation, OLS). Standard errors are in

Time period

Cooperation in labor

a

o

relations

(OLS)

C)

d

R2

Strike

activity

in

1960's

Cooperation in labor

C

relations (IV)

R2

Note: Cooperation

italics.

1985-94

1995-2002

-0.904

-1.769

-2.582

-2.548

0.406

0.648

0.767

0.571

20

21

21

21

0.216

0.282

0.377

0.512

0.967

1.515

2.219

1.785

0.432

0.712

0.766

0.572

17

18

18

18

0.251

0.221

0.344

0.379

-0.9

-1.444

-2.484

-2.461

0.633

0.928

1.017

0.695

17

18

18

18

0.19

0.325

0.412

0.532

N

0)

regression

1975-84

N

R2

first

1965-74

N

i-,

corresponds to the

in labor relation is,

from 1999 survey of managers, the answer

to question:

labor relations in your firm cooperative?". Strike activity per employee from 1960 to 1967

composite measure based on employees involved and days

and employees involved

in strikes in the 1960's to

lost.

"Are

is

a

Last regression (IV) uses days lost

instrument for 1999 survey measure.

their

standard deviation, so the coefficients are directly comparable.) For

reasons discussed earlier, both of these regressions suffer from potential

bias,

measurement

in the third line,

error for the

we

first,

simultaneity bias for the second. Thus,

report the results of estimation, using days lost per

employee and workers involved as instruments

for

the measurement error in using the strike measure

COOP.

is

If,

as plausible,

uncorrelated with the

disturbance term in the above regression, this yields consistent estimates

of the effect of the quality of labor relations

on unemployment

each

for

decade.

All three regressions suggest a strong

and

significant effect of the quality

of labor relations on unemployment.

The magnitudes

across the two measures,

OLS and IV

and across

estimation. Countries

with one-standard deviation better quality had about

ment than the average

unemployment

To

OECD

in 1975-1984,

COOP, and

The

relation

Figure

4.

is

the

OLS

1%

less

unemploy-

country in 1965-1974, about 1.5 to

about 2 to 2.5%

in 1985-1994,

give a better sense of the results, Figure 4 plots the

against

are largely similar

2%

less

and 1995-2002.

unemployment rate

regression line for each of the four decades.

quite striking, especially in the last two periods.

The

quality of labor relations

and unemployment

rates,

by decade

Standard checks suggests that this relation

is

robust. Figure 4

makes

clear

that the results are not driven by any single country. Using the underlying

components

little

DL

and

WI

separately rather than combined in

difference to the results.

makes

So does the use of the 1993 answers instead of

the 1999 answers to the World Economic

for the average

CONF

unemployment

Forum

survey. So does controlling

rate in 1960-1967. Estimating equation (4)

using annual unemployment rather than decadal averages) yields a time

series for

1980s,

estimated

bt

and decreasing

which

is

hump

at the very

shaped, reaching a peak in the mid

end of the sample.

1

1

CD

CO

c

g

CM

o

o

CM

•sj-

co

03

0)

i

LO

LO

i

LO

CD

CD

cd

01

S-_

O

JD

CO

_l

CO

Dc

c

o

CO

CD

-h-»

c

a:

o

CD

CO

E

>>

o

.Q

CO

_J

g

c o

C

o

(/)

C/J

CL

E *

hp

Q)

C LO

D

'-*—

TO

03

- LO

^1"

(7)

CD

i—

CO

CD

s.1

i

LO

00

CD

CD

CD

.

O

o

Q.

c/J

- M"

CO

Q)

L_

O

o

CO

H

CD

9L

CH

9

91

(H

9

a;ey }U8UjAo|dujaun aBejaAy

QJ

CO

The quality of labor

unemployment

4.2

An

relations, Institutions,

obvious question at this point

tions affects

unemployment

is

directly,

and

whether the quality of labor

i.e.

given labor market institutions,

The

or through these institutions themselves.

earlier description of the

Netherlands suggests the presence of at least some direct

wage moderation

tions were reformed only after

rela-

started.

effect: Institu-

We now

look at

the cross country evidence.

A

natural starting point

of institutions on

is

to use a specification which allows for

an

unemployment, and then add our measure of

Such a specification was suggested and explored

the two authors [Blanchard and Wolfers 2000].

in earlier

We

effect

quality.

work by one

of

use that specification

benchmark and estimate:

as a

=

Uit

(1

+ (fe_74 + d 7 5_84 + ^85-94 + ^95-03) (» + ^PjXij) + £«

(5)

i

We

divide time in 4 decades: 1965-74, 1975-84, 1985-94, 1995-2003

use decades to

earlier.

make the

Using half decades as

ence to the results.) uu

Xij

is

is

in

more comparable

linear

common

to the results presented

Blanchard and Wolfers makes

unemployment

in

a measure of institution j in country

the impact of the

on a

results

i.

(We

country

i

little differ-

and decade

and

t,

This specification allows for

(unobservable) aggregate shock

dt

to

depend

combination of the different measures of institutions. The

stitutions (described in Blanchard

an index of the length of time

for

and Wolfers) are the replacement

in-

rate,

which unemployment benefits are paid,

union coverage, an index of employment protection, an index of active

bor market policies, union density, a measure of the tax

la-

wedge between

the cost of labor to firms and take-home pay by workers, and a measure of

15

coordination of bargaining.

Table

2:

Shocks and institutions revisited

Results of estimation of this non-linear specification are given in Table

The

column uses only COOP, instrumented by STRIKE. This spec-

first

can be thought as the same as equation

ification

constraint across time periods that bt/at

straint

2.

close to being satisfied

is

results are very similar,

=

(4),

with the additional

constant. This additional con-

by the unconstrained regressions, so the

and our measure of labor quality

is,

as in Table

1,

very significant.

The second column

uses only the variables in Blanchard and Wolfers, and

the results are, in general, similar to theirs. Institutions are defined so that

their expected sign

on unemployment

is

positive; all coefficients turn out

to have the expected sign, although only the last 4 are significant.

The

third

column uses both

institutions

and our measure of

quality.

The

coefficient on the measure of quality decreases from -0.927 to -0.638, but

remains very significant. Interestingly, the coefficients on most institutions

become more

than

significant

in

column

2.

One might have expected

the

"coordination" variable and our quality variable to capture similar dimensions of labor relations

and be very

correlation between the

two

is

0.42),

collinear; this

is

not the case (the

and both dimensions are strongly

significant.

Column

column

up

4 excludes labor market institutions that were not significant in

3.

The estimated

to -0.834,

and

is

coefficient for the quality of labor relations goes

just as significant as in

column

1.

16

~

=

ft

u

OS

3

g

•-

•*

0\

>

"*

•-)

>

ts

B>

1

r

"!J-

>o

C)

m

cr

"i

2

"->

-T

f^

co

<^

B 3

i

:c

^ —

m

in

t^

O d

^

o Bi

C>

"1 r

o

r

r

3 s

s

a

— B! d a

Bi °

Bi

SD

CQ

I

tN

1

|

d

Bi

°

Bi

m

^

d

p!

t-

<n

P:

°°

r-

C3

a

G

3

S

v.

I

(N

"*

rn

m

o

>

^

>

i—t

Bi

ts'

CO

oj

3—

> OS

oo

<N

b>

"->

>«->

Bs

CO

so

d

oo

"1

<N

<=5

— t\

O C

a

—

c>

9

in

1

d

^o

<=j

ts

ts

tN

oo

~^

r-

m

o

d o d

"-I

Oo

<N

ta

Bi

r

--,

Os

r!

q B q

d B! d

1

CO

—

o

ci o

Bi d

?n

1

B>

Bi

d

E 2

c a*

= z

cd

£

u

>

cd

00

rs

.>

&

—

m a>

a

r,

C

3

n

-J

—V

.3

|2

—

i

0-

n

°o OS

o

^

en * (N

~

~,

cs

O

>s-i

(N

OO

B)

oo

r

t\

SO

OS

in

o o ° °0

O

o s

^

CS d

i

r->

"-,

C)

^o

rs

is-j

qi

r

m

o B en

q

d Bs d

in

]

<M

•^f

B)

O

d

---

S

fS

CQ

B>

OS

Bi

OS

m

o

"o

-~<

Br

SO

SO

r-

d B d

Ov

Vo

—

(N

P-

Os

•*

TJ

—a

^

3

Bi

V]

CQ

>

J

I z

c

<U

n.

—

-

£

3

3

01)

E

'to

a>

i

2

£

to

.Si

oo

m

^

—

'

S

<u

3

©

—

a

u

^

•n

Os

'n

m

(N

-

rsi

-^

3

c

a

r^

in

q

fS

r

1

"-

c

B

in

>C

r

l

Os

O

i

r

rs

P

1

r

1

-.

"^*

so

~

"3

d

c

o

to

°

CI

,-k

—I

"5

"^

^_

o

O

3

U

'%

'

-1

~

OJ

u —5

s 3

<L>

u

3

.-

(A

3

u

3

O

OS

s

O

(2

J-l

X

i

to

2

o

1

u

OS

OS

3

o

•*

00

os

3

in

r~

Os

Eta

i

"O

u

cd

O

•a

o

60

.3

Oh

'3

00

CJ>

-

n. -a

n

33

H

CX,

to

"">

3 so

3

E 2

fe

—O tou

J3

-°cd

'C

cd

*

a--

y

m

oo

cr-

m

o

©

i

<n

3>

~

>,

>>

>>

3

3

3

3

S

E

a

Q

> a

CO

o

j^

t-i

3

=;

—

"_*

C3

J

to

13

p4

3

g

u

V.

s

D

E

u

o

3

Q

Ifl

<L>

1—

D

'^

ai

o

r-

o

3

D

m

00

U

>

o

:^

's

D

o

-o

^3

U

3

O

to

t-l

fj

Q.

S

UJ

t)

O

a

1>

,S

oi

Q

>

3

O

o

<

3

D

all

:>

CQ

-C

2

0.

o

.£

to

3

U

-J

to

3

>

o

c

D,

to

t/1

D

™

5

^

:-

O

o

U

^ 2

Conclusions and open issues

5

We

see the point of our paper as arguing that, in addition to formal in-

stitutions, the quality of labor relations

matters in the determination of

unemployment. Faced with adverse shocks, such as those Europe has faced

in

the last three to four decades, countries with better relations appear to

have been better able to limit the

unemployment and

rise of

to turnaround

faster thereafter.

This

is

both good and bad news

ployment

Europe. The good news

in

clearly important,

bad news

is

for those

good labor

is

who want

to achieve lower

that, while institutional reform

by themselves, go a long way. The

relations,

for

the 1960s and the late 1990s, the

quality of labor relations appears slow to change over time,

last

remark points to the obvious

of a theory for

and how

and we

The

it

what determines the

shall limit ourselves to

or country characteristics.

rate of firms clearly differs

Most

for firms to

limit of our paper,

socialist

a few remarks

is

The

if

at

all.

namely the lack

quality of labor relations, and whether

can be improved over time. This

quality of labor relations

unions.

is

that, based on the informal evidence as well as the correlation

between our two measures of quality

This

unem-

is

a large and

difficult topic,

3

.

clearly correlated

with a number of union

attitude of unions with respect to the profit

between communist,

socialist,

and social-democratic

and social-democratic unions now recognize the need

maintain an adequate profit

rate.

The

rhetoric of

many com-

munist unions, on the other hand, remains largely similar to what

30 years ago.

The

it

was

same holds not only for unions, but also for political par-

and Philippon [2004] study the link between labor relations and the control

They find that, across countries, bad labor relations are associated with more

family control, while good labor relations are associated with more dispersed ownership

of shares. They argue that bad labor relations and tight family control reinforce each

other. This may explain the persistence of bad and good relations that we see in the

3.

Miiller

of firms.

data.

17

ties.

of

4

Our

quality measure

communist votes

is

indeed strongly correlated with the number

Whether

in elections in the 1960s.

this

should be taken

as correlation, or as a proximate cause for the quality of labor relations,

still

is

unclear.

Some evidence

suggests, however, that the quality of labor relations can

change over time. The example of the

UK

appears relevant here. Unions

were surely made weaker by the policies of Margaret Thatcher; but there

is

wide agreement that they have also changed their attitude (although the

improvement

where the

in the quality of labor relations

UK

is

right

on the regression

is

not visible in our Figure

3,

line...)

Indeed, the best known early statement of the need for "a partnership between capital

and labor" is by Helmut Schmidt, then the Social Democratic Chancellor of Germany,

in 1976: "The profits of entrcprises today are the investments of tomorrow, and the

investments of tomorrow are the jobs of the day after"

4.

18

Appendix. Derivation of the wage under learning.

Let pt be the subjective probability held by the union at time

and

extract

fit

=

From the

po be the prior.

let

realized

.

t

{ao, 01,

..,

sets the

t

Vt+l

t is

therefore

wage one period

in

advance,

[wt+in t +i\

given by:

is

w +i

t

E

^h+i]

=

union can

bill

wt+i = argmax£

where 6

= g,

at}.

maximize the expected wage

the wage

nt, the

but not a* The information set at the end of period

a<

Under the assumption that the union

to

employment

that g

t

t

[(at+1 )-

1

]

i-r+s

2

Bayesian learning in turn implies

Pt

=

prob(g

=

prob{a t

|

g

|

fi t _i,

fit-i, g

a

=

prob(a

t )

g)prob{g

t

|

=g

|

fi f -i)

fit-i)

Pt-i

pt-i

+(1 -p -i)exp(^f

4

Along the path where e

=

and

<?

=

0,

((log at

2

-gi) -(loga,)

2

))

we have

Pt-i

Pt

Pt-l+(l-R-l)exp(^-)

1M

where we see that p decreases toward

t

0.

Along

this path, the

wage

is

a2

h -

and employment

4>e

Vt-\e~

a

=

2

+ 1-

Pt-l

is

nt =

The

9t

1

+

0(1

-w

t

-r)

values used to derive the path in Figure 2 are p(0)

.02, r

=

.1

and

6

=

=

0.98, g

=

.01,

1.

20

References

[1]

Olivier Blanchard

rise of

and Justin Wolfers. Shocks and

institutions

European unemployment. The aggregate evidence.

and the

Economic

Journal 110(1): 1-33, March 2000.

[2]

Douglas Hibbs. The

political

economy of industrial democracies. Har-

vard University Press, 1987.

[3]

Peter Katzenstein. Small states in world markets. Cornell University

Press, 1985.

[4]

Holger Miiller and

Thomas

Philippon. Corporate ownership and labor

relations (around the world),

[5]

Stephen

Nickell

mimeo NYU,

2004.

and Jan van Ours. The Netherlands and the United

Kingdom: a European unemployment

miracle.

Economic

Policy, 30,

April 2000.

[6]

Ronald Schettkat. Are institutional

rigidities at the root of

European

unemployment? Cambridge Journal of Economics, 27:771-787, 2003.

[7]

Jelle Visser

and Anton Hemerijck.

A Dutch miracle.

reform and corporatism in the Netherlands.

Press,

Job growth, welfare

Amsterdam

University

Amsterdam, 1997.

21

9

1

»-\

~

Date Due

MIT LIBRARIES

3 9080 02618 0106

T»I

lifi

'

''!i;-i

m

m