Document 11163054

advertisement

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/roleofinformatioOOdufl

3B31

.M415

l^W£\

13

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND SOCIAL

INTERACTIONS IN RETIREMENT PLAN DECISIONS:

EVIDENCE FROM A RANDOMIZED EXPERIMENT

Esther Duflo

Emmanel Saez

Working Paper 02-23

March 21 ,2002

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 021 42

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://papers.ssm.com/paper.taf7abstract

id=XXXXXX

MASSACHui^'l

.

,;

v;

OFT'

JUN 1 3

2002

"libraries

<tf

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND SOCIAL

INTERACTIONS IN RETIREMENT PLAN DECISIONS:

EVIDENCE FROM A RANDOMIZED EXPERIMENT

Esther Duflo

Emmanel Saez

Working Paper 02-23

March 21, 2002

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 021 42

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

h1tp://papers. ssrn. com/paper. taf?abstract id=XXXXXX

The Role

of Information

and Social Interactions

in

Retirement

Plan Decisions: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment

MIT and NBER

Esther Duflo,

Emmanuel

Saez, Harvard University

March

21,

and

NBER*

2002

Abstract

This paper analyzes a randomized experiment to shed light on the role of information

and

social interactions in employees' decisions to enroll in

retirement plan within a large university.

a Tax Deferred Account (TDA)

The experiment encouraged a random sample

of employees in a subset of departments to attend a benefits information fair organized

the university, by promising a monetary reward for attendance.

The experiment more than

tripled the attendance rate of these treated individuals (relative to controls),

that of untreated individuals within departments where

enrollment 5 and

1 1

months

after the fair

was

on

TDA

enrollment

receive the

treatment

results.

is

nobody was

almost as large for individuals

encouragement as

for those

network

effects, social

who did. We

effects,

some individuals were

significantly higher in

individuals were treated than in departments where

in

by

and doubled

treated.

TDA

departments where some

treated. However, the effect

treated departments

who

did not

provide three interpretations, differential

and motivational reward

effects, to

account for these

(J EL D83, 122)

'We thank Daron Acemoglu,

Orley Ashenfelter, Josh Angrist, David Autor, Abhijit Banerjee, David Card,

Jonathan Gruber, Guido Imbens, Larry Katz, Jeffrey Kling, Botond Koszegi, Michael Kremer, Alan Krueger,

David Laibson, Sendhil Mullainathan, and seminar participants

very helpful comments and discussions.

Foundation (SES-0078535).

for their help

and support

or its benefits office.

We

in

We

at Berkeley,

MIT, Princeton, and

UCLA

for

gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science

are especially grateful to

all

the

members

of the Benefits Office of the University

organizing the experiment. This paper does not reflect the views of the university

1

Introduction

Low

levels of savings in the

of

what determines savings

United States have generated substantial interest

A

decisions.

in

the question

vast literature has studied the impact of

Tax Deferred

Accounts (hereafter, TDA), such as Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and 401 (k)s, on

re-

tirement savings decisions, 1 and, concurrently, the impact of these plans' features on enrollment

and contribution

ployer's match), a

rates.

In addition to the tax savings and economic incentives (such as em-

number

of recent studies emphasize the role of non-economic factors, such as

social interactions, financial education, inertia,

how

individual participation in a

ticipation in one's department.

TDA

(2001a, 2001b)

plan within a large university

They obtain

influence on the decision to enroll in

show that default

TDA

When

is

affected

by average par-

suggestive evidence that peer effects have a strong

plans.

rules have

contribution, and asset allocation.

and commitment. Duflo and Saez (2000) study

Madrian and Shea (2001) and Choi

et al.

an enormous impact on employees' participation,

employees are enrolled by default in a

TDA.

very few

opt out and most employees do not change the default contribution rate or the default allocation

of assets.

Thaler and Bernatzi (2001) show that inducing employees to commit to contribute

a large fraction of their pay raises to the

TDA

dramatic positive impact on savings

Bernheim and Garett (1996) and Bayer, Bernheim,

rates.

(the "Save

More Tomorrow" program) has a

and Scholz (1996), Bernheim, Garett and Maki (1997), among others, study the

education.

They

role of financial

present evidence that financial education tends to be remedial 2 but that

increases participation in savings plans, suggesting that employees

may

it

not be able to gather

the necessary information on their own. This evidence, though suggestive, does not provide fully

convincing proof that information and financial education can have a strong impact on

participation decisions, because employers' decision to provide this information

is

TDA

endogenous.

Recently, Madrian and Shea (2002) studied the effects of benefits seminars within a large firm

and showed interesting evidence of

who

attend seminars are

self-selection in the decision to attend benefits:

much more

likely to

be recent enrollees

in

the

TDA

plan.

employees

They found

'See Poterba, Venti and Wise (1996) and Engen, Gale and Scholz (1996) for a controversial debate summarizing

the literature.

2

Employers resort to

it

when they

compensated employees are too low.

fail

discrimination testing because the contribution rates of the not highly

modest

on

positive effect of information seminars

Financial education

is

participation after a few months.

generally recognized as an potentially important avenue to improve

71%

the quality of financial decision making.

financial information sessions.

A

of the fortune 500 companies systematically hold

10% conducts them

further

(Summers, 2000) outlined a proposal to improve

financial services of lower

TDA

occasionally. 3

financial literacy

The U.S. Treasury

and increase the access to

income American households. In particular, the report stressed the

importance of information on savings instruments and the role of social interaction

decision to save.

shed

light

The

goal of this paper

on both the

is

and

social interactions

TDA plan of a large university.

enroll in the employer sponsored

random experiment

to analyze the evidence from a

role of information

effects in the

to

on the employees' decision to

Our

analysis improves

upon the

studies discussed above because the source of identification comes directly from the randomized

experiment. This allows us to overcome some of the very

presence of peer

Each

effects,

to provide information on benefits.

TDA, which

Obviously, comparing the

attend the

TDA

fair

all its

employees to a benefits

In particular, a stated goal of the fair

the university administration feels

TDA

enrollment decisions of

enrollment, because the decision to attend the

fair

TDA

This data come from a telephone survey of

In spite of these difficulties, there

which essentially focuses on

is

all

is

fair in

order

to increase the

is

too low (around 35%).

attendees to those

who

did not

of a causal effect of fair attendance

fair is

endogenous. 5

we have implemented the following experiment.

of employees not yet enrolled in the

3

and invites

would not provide convincing evidence

selection problem,

the

in

described notably in Manski (1993, 1995). 4

year, the university organizes

enrollment rate in

problems

difficult identification

To circumvent

We selected

and sent them an invitation

500 companies we conducted

in

letter

the

a

on

this

random sample

promising a $20

summer

2001.

a growing empirical literature on peer effects using observational analysis

social behavior,

and the adoption of new technologies. For example, Case and Katz

(1991) and Evans, Oates and Schwab (1992) on teenagers' behavior, Bertrand, Mullainathan and Luttner (1998)

on welfare participation, Munshi (2000a) on contraception, and Besley and Case (1994), Foster and Rosenzweig

(1995) and Munshi (2000b) on technology adoption in developing countries. Sorensen (2001) analyzes peer effects

within departments of a university

in

the choice of Employer sponsored Health Plans using a methodology related

to Duflo and Saez (2000).

For example, individuals who had already decided to

to contribute,

may

be more

likely to

attend the

decision to attend information sessions.

fair (see

enroll,

but are not sure exactly

Madrian and Shea (2002)

for

how much they wanted

evidence of selection

in

the

reward

for

attending the

fair.

This type of experiment

is

a classical encouragement design, often

who

used in medical science, where treatments are offered to a random group of patients

then

decide whether or not to take the treatment. 6 Encouragement designs are rare in economics.

An example

on

test scores

who

the study by Powers and Swinton (1984)

is

by randomly mailing

analyze the effect of hours of study

test preparation materials to students to

encourage them to

study.

The second

objective of our study

designed our experiment such that

who were

"treated" individuals

is

we

to analyze peer effects within departments.

are able to estimate social interaction effects.

sent the invitation letter were selected only from a

subset of departments (the "treated" departments)

A

.

number

is

random

effects.

Kremer and

perhaps the most closely related to our study. They analyze an experiment

design to evaluate

own and

external effects of a medical treatment against intestinal

children in schools in Kenya,

in treated schools

Namely,

of recent studies have also used

experimental or quasi-experimental situations to study social interaction

Miguel (2001)

We therefore

who

and obtain evidence of

spillover effects.

worms

They show that

for

children

did not get the medicine were positively affected. However, in their case,

variation in treatment status within a school

was not randomized but occurred because some

children were not present on treatment day.

Katz

et al.

(2001) use

random assignment

to a

housing voucher program for households living in high poverty public housing projects in the

Boston area and find improvement of treated families

Sacerdote (2001) uses random assignment of

and finds peer

social groups.

first- year

effects strongly influence levels of

These

latter

two studies on

in safety, health,

and exposure to crime.

students in Dartmouth college dorms

academic

effort as well as decisions to join

social interactions differ

from ours mainly because

they study the effect of assigning individuals to different peer groups, whereas in our study,

peer groups (departments) are fixed, and

we analyze how

individual decisions are affected by an

exogenous change on the information set of some members of the peer group.

The

6

first

stage of our study analyzes the effect of the invitation letter on fair attendance.

For example, Permutt and Hebel (1989) study the effect of maternal smoking on birth weight using randomly

assigned free smoker's counseling to encourage mothers to quit smoking.

effect of flu

shots

(recommended but not required) to a random subset

Imbens

et al.

(2000) analyze of the

of patients on flu outcomes.

'Following our previous discussion, the voucher program can be seen as an encouragement design to leave

public housing projects.

Treated individuals are three times as likely to attend the

ingly, control individuals in treated

fair as control individuals.

departments are twice as

likely to

attend the

Interest-

control

fair as

individuals in non-treated departments, despite the fact that only original letter recipient could

claim the $20 reward.

tendance rate

This shows that the invitation letters not only increased the

for individuals

who

received

The

colleagues within departments.

them but had

also a spill-over social effect

direct effect of the letter

fair at-

on

their

on attendance (purged from the

peer effects) can also be estimated by comparing the attendance rates of treated and control

individuals within treated departments only.

The second

effects

stage of the study tries to estimate the causal effect of

on the decision to

enroll in the

TDA. We show

individuals in treated departments are significantly

the

TDA

than control individuals.

successful in increasing

TDA

enrollment between those

departments who did not.

of the financial

colleagues,

and

for the former.

fair

was

is

no significant difference

propose three different interpretations, not necessarily mutually

TDA

First, this

enrollment.

might be evidence of

differential

Employees who come to the

plausible to think that the treatment effect

is

fair

fair

treatment

only because

because of their

larger for the latter

group than

Second, there might be social network effects within departments. Fair attendees

affect their subjective

information they obtain at the

literature.

fair,

same

might also be explained by motivational reward

might

have started contributing to

reward are different from those who decide to come to the

it is

after the fair,

actually received our encouragement letter and those in the

However, there

might be able to spread information obtained from the

results

months

TDA

We

attendance on

likely to

11

in

exclusive, to account for these facts.

effects of fair

and

attendance and social

This shows that our experiment, and hence the

enrollment.

who

more

that, 5

fair

fair in their

effects.

departments. Third, our

Paying individuals to attend the

motivation and therefore the perceived value or quality of the

fair.

Such

Our experiment does not

effects

have been documented in the social psychology

allow us to separately identify these three effects but

allows us to conclude that the important decision about

how much

it

to save for retirement can

be affected by small shocks such as a very small financial reward and/or the influence of peers,

and thus does not seem to be the consequence of an elaborate decision process.

The remainder

of the paper

is

organized as follows. Section 2 describes the benefits

fair

and

the design of our experiment. Section 3 discusses the reduced form evidence. Section 4 develops

a simple model to guide the subsequent analysis of our results. Section 5 provides additional

evidence from a follow-up questionnaire and a general interpretation of our results.

Finally,

Section 6 offers a brief conclusion.

Context and Experiment Design

2

Benefits and Benefits Fair

2.1

The

university

we study has approximately 12,500 employees. About a quarter

members.

are faculty

Our study was

provides retirement benefits to

its

8

limited to non-faculty employees only.

of the employees

The

employees through a traditional pension plan and a comple-

mentary Tax Deferred Account (TDA) plan. Part of the traditional pension plan

Contribution (DC) plan whereby 3.5% of an employee's salary

tual fund account.

9

university

Employees can

is

also voluntary contribute to a

is

a Defined

put into an individual mu-

TDA

403(b) plan.

10

Every

employee can contribute to the 403(b) plan any percentage of their salary up to the IRS limit

($10,500 per year for each individual in 2001).

In both the

number

DC

and the

TDA

The

university does not

match contributions.

plans, employees can choose to invest their contributions in

any

of four different vendors.

Each

year, the university organizes a benefits fair

and learn about

university.

The

all

where

all

employees are invited to come

benefits (such as health benefits, retirement benefits, etc..) provided

fair is

held on two consecutive days in early

November

in

two

by the

different locations,

each one close to the two separate main university campuses. About one week before the

every employee receives a letter through university mail inviting her to attend the

letter also provides a brief description of

fair.

fair,

This

the event. At the same time, under separate cover, every

employee receives a packet describing in detail university benefits along with enrollment forms.

November

choices

8

is

by submitting the enrollment form.

lo

If

may change

TDA

choices are not influenced by

and vice-versa.

Non-faculty employees have an additional Defined Benefits plan in addition to the

403(b) plans are very similar to the better

firms.

her benefits

the employee does not send back the form, her

Duflo and Saez (2000) present suggestive evidence that staff employees

faculty choices

9

"open enrollment" month during which each employee

known 401 (k) plans but

their use

is

DC

plan.

restricted to not- for-profits

benefits choices are automatically carried over

free to enroll in

the

TDA

from the previous year. However, employees are

or change their contribution level or investment decision at any time

throughout the year.

In both locations, the fair

is

held in a large hotel reception room. There are a large

number

of

stands representing the university Benefits Office, and the various health and retirement benefits

The

service providers.

university Benefits Office offers information on

conversation with benefits office staff present at the

pamphlets

freely available at their stand.

The

benefits through direct

all

and through a number of information

fair,

benefits office also provides information on

how

the other stands at the fair are organized. These other stands are run by each of the specialized

service providers.

For example, each of the mutual fund vendors has a stand at which they

provide information about the

The

fair

TDA

plan and the specific services they offer within that plan.

computer program to

also offers individuals the chance to use a specially designed

come anytime during the three and

analyze their specific situation. Employees are free to

hours during which the

fair is held,

and

visit

a half

any number of stands they want.

Experiment Design

2.2

The

university organizes the annual fair in order to disseminate information about benefits and

help

its

(34%)

is

employees make better decisions. The university

too low compared to other universities, and that this

A simple comparison

to change their benefits choices

may be more

identify the causal effect of fair attendance

fair.

on

TDA

We

attend the

enrollment,

fair.

we

TDA

work (Duflo and

are very correlated

Saez, 2000),

among

we have shown

within departments, not

can thus measure peer

peers that did.

all

among

staff

to lack of information.

fair

and those who

Clearly, those

effect of the fair.

likely to

who

plan

Therefore, in order to to

set

up an "encouragement

for attending the

that the decisions to participate

individuals within departments, which suggests the

existence of social effects in enrollment decisions.

effects

may be due

by promising a random subset of employees a small amount of money

In previous

into the

the participation rate

between the benefits choices of those who attend the

do not does not provide an unbiased estimate of the

design",

feels

Therefore, in order to shed light on social

individuals within the treated departments received a letter.

effects using individuals

who

didn't receive a letter, but

who had

We used a cross-section of administrative data provided

as of

aged

We

August 2000.

less

criteria,

than 65 and

sample to

restricted the

eligible to participate in the

around 3,500 were enrolled

TDA

in the

TDA

employees

staff

TDA. 11 Of the

as of

all its

9,700 employees meeting these

From now

August 2000.

once they are enrolled, 12 we focus on the decision to start participating into the

sample of 6,200 non-enrolled individuals

In the

first step,

we randomly

is

selected

we

on,

refer

6,200 individuals were not

As very few employees stop contributing

by August 2000.

employees

non-faculty employees)

(i.e.

The remaining

to these individuals as the pre-enrolled individuals.

enrolled in the

by the university on

to the

TDA

TDA. Thus

the

our sample of primary interest.

two thirds

of the

departments of the university (220

out of a total of 330) as follows. In order to maximize the power of the experiment (in a context

in

which we know there are strong department

to their size

number

(i.e.

of employees)

effects),

we

and participation rate

separated department into deciles of participation rates

We

33 departments.

first

then ranked them by

size

matched departments according

TDA

in the

among the

staff.

before the

Each

fair.

We

decile contains

within each decile, and formed groups of three

departments by putting three consecutive departments on these

lists in

the same

triplet.

Within

each of these triplets, we randomly selected two departments to be part of the group of treated

From now

departments.

we

on,

refer to the treated

departments as the

T

departments and to

departments.

the control departments as the

In the second step, within each of the treated departments, any individual not enrolled as of

August 2000 was selected with probability one

individuals.

for

We

Treated department and

for

1

who were

where no treatments were

One week

before the

fair,

Part time employees working

we

less

it

is

denoted by

TO (T

being selected). In total, there are 4,168 individuals in

control group

selected;

composed of 2,039

being selected). The group formed by the employees in the

for not

The

is

and denote them by Tl (T

not selected contains 2,129 individuals and

Treated department and

the treated departments.

11

This treatment group

referred to this group as the Treated individuals

treated departments

for

half.

is

formed by employees

contains 2,043 individuals and

in the control

is

denoted by

departments

0.

sent a letter via university mail to the 2,039 employees in the

than 20 hours per week are not

eligible for the

TDA. Most

of these employees

are students of the university.

12

Only 80

of the 3,500 employees enrolled in the

examine. More than

five

times as

many employees

TDA

stopped contributing during the one year period we

started contributing to the

TDA

during the same period.

treatment group T\. The letter reminded them of the

receive a check for $20

letter is

reproduced

At the

their

fair,

we

from us

if

they were to come to the

up a stand

and

fair

register at our desk. This

appendix.

in facsimile in the

set

and informed them that they would

fair

for the

name. Unfortunately, the benefits

employees

office did

who

received our invitation letter to register

not authorize us to record the names of the

participants

who

stood at the

fair

coupons had

different colors according to the status of the participant (active or retired),

did not receive our letter. However,

number

We are thus confident

carefully counted.

In order to collect information on the

we organized a

had two

parts, with a

in the raffle

affiliation

raffle.

TDA

gave us half of the coupon.

fair.

and

TDA

asked

departments

versus

affiliation

and

TDA

in

An

who

status).

attendant

fair

all

the

in the

letter.

raffle

raffle

A

Out

affiliation of all

we assume

between

want to stay

raffle

was held every 30

employees

total of 1,617 active

of the remaining 1,044 employees,

is

their

department

that fair attendants

T and

who

(and hence provide their department

enough to wait

who

for the

departments as those who did

what

register. Therefore, in

1,

044/766.

In order to assess the effects of the experiment and the fair on

We

present in Section 5 evidence supporting our non-selection hypothesis.

modifying this assumption would

next

raffle.

refused

had been

Therefore,

did not register their department affiliation are distributed

the attendance recorded in each department by a factor of

1

affiliation

whether there was selection by

do not believe this was the case: most of those

at the fair long

fair

to participate

to play the raffle did so because they visited our stand just after the previous raffle

played, and did not

the

participants their department

and registered

raffle

of participants.

who wanted

TDA. The

important issue that arises

decided to play the

We

which

distributed at the entrance of the

gift certificate.

573 of them had received our

enrollment status.

The

Everybody had to

fair.

and the department

Each

twice.

about three quarters) came to play the

(i.e.,

T

status

We

entered the hall.

we accurately recorded the number

and whether they were currently enrolled

attended the

attended the

The coupons that were

number written

who

number: a student

and the few people who refused the coupon were

fair,

that

minutes, and the prize was a $50 Macy's

766

who

of active employees

pass through the narrow entrance enter the

fair

their total

entrance and distributed a coupon to each person

allowed us to count the

participants,

we recorded

fair

affect our result.

follows,

we

scale

up

13

TDA

participation, the

However, we

will discuss

how

The

university provided us three waves of data.

before the

wave from October 2001

2001.

we

wave was obtained

The second wave was from March 2001

fair.

Finally,

first

(11

months

months

(4.5

after the fair)

just

and the third

sent a short questionnaire (reproduced in the appendix) to 917 employees in April

The questionnaire was designed

to assess the intentions and evaluate the knowledge of

An

additional goal of sending out the questionnaire was

to remind those that were not yet enrolled of their

a cue to think about enrolling in the

they were enrolled in the

TDA, why

TDA.

TDA

to send back the questionnaire,

In the questionnaire,

we promised a $10 Macy's

we

we asked employees whether

they were not enrolled, whether they saved for retirement

would send back the questionnaire within 6 weeks.

questionnaire as follows. First,

and (potentially) provide them

status,

through other means, and whether they had attended the

restricted the

We

fair.

In order to induce employees

gift certificate to

any employee who

selected 917 employees to receive the

sample to those who were not enrolled

in the

by March 2001. Second, one third of employees (301) were selected among the 573

participants

selected

fair.

September 2000,

after the fair).

employees about retirement benefits.

TDA

in

who

among

The

did receive the invitation letter.

the 1,499 employees

last third (305)

invitation letter). 14

of questionnaires

We

who

The second

fair

third (311) of employees were

received the invitation letter but did not

were selected among our control group (those

who

come

to the

did not receive the

did not intentionally leave out any departments, but since the number

was not very

large, there are a

number

of

departments where we did not send

any questionnaire. 15

Results:

3

Summary

statistics

and Reduced form

In the presence of social interactions, employees

who work

themselves.

They may be more

likely to

come

14

Out

15

These departments tend to be smaller, but once we control

department belongs, the difference

16

This

is

in size

something we observed at the

is

small.

fair.

TO

if

they did not receive the

letter

to the fair themselves, because they are reminded

by others of the event, or because employees come to the

of these 305 individuals. 160 are from the

departments where some people

in

received the letter can be affected by the experiment even

differences

fair in

groups. 16

They may

control group and 145 are from the

for

the

dummy

also be

more

control group.

indicating in which group the

likely to enroll in

the

TDA

even

they do not come to the

if

fair

by the action of those who went to the

are directly influenced

share the information they gathered at the

themselves, either because they

or because these individuals

fair,

Thus, employees are potentially subjected to

fair.

two kinds of treatments: they can receive the invitation

can be in a group where some employees received the

letter

letter

themselves (group Tl), and they

(departments T). Those

who

receive

the letter are, obviously, subject to both treatments.

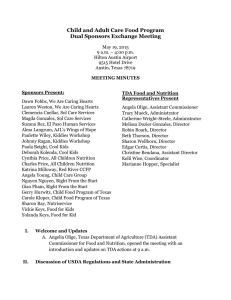

The summary

statistics are displayed in

we present the

to (3),

Table

statistics for individuals

1,

broken down into 4 groups. In columns

who belong

has the statistics for the entire group (group T), column

(1)

group of treated individuals (group Tl), and column

individuals in treated departments (group TO).

individuals

who belong

first

individuals not enrolled in the

differences in the

which includes a

level.

1

'

same

the

fair),

(1), (2), (3),

and

(2)

column

(4),

we

It is

present the statistics for

important to note that

all

and the second row of Panel B) focus only on

The

fair.

In Table

differences are estimated

and corrects standard

TO and group

for the

has the statistics for the untreated

on September 2000 before the

(4) present

has the statistics

Column

group Tl and group

presents background characteristics.

In the

first

we

present

by a regression,

errors for clustering at the

the differences between group

0,

2,

T

department

and group

0,

respectively.

wave (on September 2000 before

a very small proportion of employees started contributing to the

TDA

(the

first

wave

from September 2000, but we used data from August 2000 to construct the randomization),

but there

in

A

TDA

A

variables across groups.

group Tl and group TO, group

Panel

row of Panel

triplet fixed-effect,

Columns

In

(3)

to the untreated departments (group 0).

these statistics (except the

is

to treated departments T.

(1)

is

no apparent difference across groups

changes caused by the

were

still

fair,

not enrolled in the

we

first

in these proportions.

Since

we

are interested

focus in the remaining of the analysis on individuals

wave

(i.e.

who

by September 2000). Since the groups were chosen

randomly, the mean of observable characteristics such as sex, years of service, annual salary, and

age, are very similar across groups.

In panel B,

As

it

it is

visible

we can

As expected, none

of the differences are significant.

see that our inducement strategy

from inspecting Table

1,

had a strong

effect

on the probability

this does not affect the point estimates of the differences.

However,

reduces the standard errors, by absorbing some unexplained differences across departments of similar sizes and

pre-fair

TDA

enrollment rates.

10

of attending the fair: in treated departments, as

In control departments, fewer than

is

highly significant (Table

5%

column

2,

much

of individuals attended the

receive the letter.

is

28%, and

Thus, the direct

which are the same

for

is

enrolled.

The

account

fair

attendance.

15.1%

for

those in the treated departments

fair

group (which

is

The

(3) of

control departments

TDA

is

small and insignificant.

10%

at the

level.

1.26 percentage points

is

still,

and the

and

1.4 percentage point

The

enrollment).

difference

The

difference

people update their

difference

20%

TDA

significant as well

TDA

group

19

TDA

If

enrollment.

it is

is

parallelled

24%

be

increase

represents a

now

is

is

19%

positive, but

positive,

and

increase

still

very

significant

This impact

is

by an increased

point estimate in table 2

is

in their

large in relative

However, because

small in absolute terms (an increase of

is

tiny

compared to interventions

we made about department

we make the extreme assumption

fair participation rate for

(which would go up to 9%). In addition,

The

likely to

enrollment (such as in Marian and Shea (2001), and Choi

of course sensitive to the assumption

departments, the

group

(it

between group TO and group

status very infrequently,

did not register at our desk.

from

18

Eleven months

significant.

in the likelihood of enrollment after 11 months).

that change the default rules for

who

2).

between treated departments and

only 1.5% points of enrollment, on a base of 36%)). This effect

is

Table

Obtaining significant differences between these randomly chosen groups means

terms (an increase of

This result

and

between groups Tl and TO

that our experiment did have an impact on

18

due to

no significant difference between groups Tl and TO, however. 19

is

after the fair, enrollment is higher

in

solely

After 4.5 months, relatively few people have

participation.

between groups TO and

difference

effect,

13.8%. The

is

enrolled than employees in control departments (4.9% versus 4%). This represents a

There

a

did not

out any social

Table 2

(2) of

who

However, employees in treated departments are already significantly more

in the enrollment rate.

for

attendance rate of those

effect of receiving the letter (taking

between the TO group and the

TDA

look at

controls in the

social effects

almost as high, at 10.2%, and highly significant (see column

we

In Panel C,

shows that

groups TO and Tl) displayed on column

difference in the attendance rate

social effects)

is

1

fair.

difference, 16.5%,

on

large part of the effect of our experiment

received our letter

The

fair.

Comparing treated individuals versus

(1)).

treated departments in columns (2) and (3) of Table

who

21.4% of individuals attended the

as

TDA

TO group would

we show below

fall

that

down

affiliation of fair

non registered individuals come

all

to

11% but

that the increase in

11

t-statistic of

about

1.

be higher than

for

attendance in the

TO

still

fair

participation.

even slightly negative, with a

attendants

(2001a, 2001b)) or that offer individuals the option to allocate automatically future pay

et al.

rises to

TDA

contributions (Thaler and Bernatzi (2001)).

summary, the

In

a large

effect

on

encouragement

on

effect

TDA

who

we present

and

in Tables 1

2 suggest that the incentive

scheme had

participation of treated departments (due to a combination of the direct

fair

effect

and the multiplier

effect of social interactions), as well as

a significant

enrollment. This shows that the fair had an effect on the decision to enroll in the

TDA. However,

those

results

within treated departments, there

who

received the letter and those

is

no difference

The next

did not.

in

TDA

enrollment between

section presents simple models

to interpret these results.

Understanding the Effects of the Experiment

4

Fair attendance

4.1

Let us

analyze the decision to attend the

first

with

letter

its

As we have

fair.

promise of a $20 reward increases the probability of attending the

this increase in the probability of attending the fair

effects in the decision to attend the fair

individuals.

form

seen, receiving our invitation

A

because

TO

by

<5.

As we have

individuals are

simple way to capture these two effects

more

fair.

Denote

seen, there are peer

likely to attend

than

to posit the simple following reduced

is

specification:

f = 5U + liD + e\

1

where

U

is

/'

a

is

the

dummy

dummy

for

attending the

fair for

f.i

in (1). Actually, these

presented in Table

20

As

/*

is

2.

e'

%

is

and

a

is

number

is

random

D

l

a

individual effect,

dummy

indicator for

Table 3 presents the estimation parameters 5

in the

Taking the difference of the averages of equation

a 0-1 variable, equation (1)

to ensure that this

(1) of

e

two parameters were already estimated

reduced form results

(1) across

groups T\ and

not strictly correct. The left-hand-side should be replaced with the

probability of attending the fair for individual

of

i,

indicator for receiving the inducement letter,

being in a treated department. 20 Column

and

individual

(1)

i,

and

always between

restrictions

and

1.

imposed on the parameters and the distribution

These

technicalities can

thus are ignored to keep the presentation focused on identification questions.

12

be taken care of easily and

TO shows

that S

group Ti,

i

TO and

=

= 0,1.

fri

—

fro where fri denotes average fair attendance

shows that

=

fi

fro

—

/o-

given department decides to go to the

them information about the

her colleagues attend the

might talk about

it

sufficiently

if

Second,

fair.

for

it

can take two forms.

fair

is

First,

if

an individual in a

she might talk to her colleagues about the

them

who

We

who

received the letter divided by the

model these peer

each department influence the individual

number

fair, it

effects

must be

number

of

of employees in the department) in

attendance decision.

fair

the letter rate in the department of individual

fair

may

by assuming

Let us denote by / the average attendance rate in the department of individual

on

and thus

received the letter

ready to pay some people $20 to attend the

as well.

fair,

that the average fair attendance rate and the average "letter rate" (defined as the

employees

give

employee receiving the

she does not go herself to the

if

For example, colleagues of those

them to attend

fair,

to join her, and thus increase the probability

also conceivable that an

is

to her colleagues, even

the benefits office

important

fair,

details, or ask

also affect their attendance rate.

think that

individuals in

Similarly, taking the difference of the averages of equation (1) across groups

Peer effects in the decision to attend the

letter

among

The

i.

and by L

i,

invitation letter effect and the peer effects

participation can be captured by the simple following linear model (see e.g.

Manski

(1993))

f

where v l

is

the random individual

i

=

5Li

effect,

+AL +

and

(3\

<

1,

equation states that getting the letter increases the

and the probability of everybody

of employees in the department),

1

in the

/31

f

+v

and

own

A

i

(2)

,

are the peer effect coefficients. This

probability of attending the fair by 5,

department of attending by A/TV (N being the number

and that an exogenous

percent translates into a final increased

fair

direct increase in fair attendance of

attendance of 1/(1

—

(3\)

percent through the

multiplier peer effect.

Obviously, our experiment does not allow us to identify

because we have only two instruments: receiving the letter

being in a

T

all

L

1

three parameters

and the

dummy

5,

A, and

indicator

D

l

(3\

for

(versus 0) department. However, the following semi-reduced form of equation 2

identified,

13

is

f = 5L + 5 R L + v'\

i

Equation

(3)

can be easily derived from

by

(2)

first

(3)

averaging equation

obtain an expression for /, and then plugging this expression for / in

that 5 R

= —S +

+

(A

—

<5)/(l

/?i).

The parameters

5

our experiment 21 and can be estimated with an IV regression using

Column

number

(2) of

Table 3 presents the estimate of equation

of letters

is

0.28,

and

is

an increase

significant:

in

The

(3).

10%

U

by department to

Simple algebra shows

(2).

and 5 R of equation

(2)

(3) are identified

and

D

1

as instruments. 22

coefficient of the average

in the proportion of people

received a letter in the department lead to an increase of 2.8% in participation of those

not themselves receive the

It is

perhaps reasonable to impose the additional restriction on equation

In that case, equation (2)

fair.

is

identified

fair

and

j3\

attendance only

and

D

l

we obtain

The

as instruments.

for

large

is

/3i

results are reported on

is

1/(1

—

letter will induce,

the

TDA

4.2.1

is,

if

A=

0, i.e.,

she decides to go

column

by September 2000, using

(3) of

in

Table

3.

The estimate

attendance increases the

by 7.5%. Put another way, the multiplier peer

an additional person induced to go to the

effect,

that

(2)

fair

because of the

on average four additional individuals to attend

Participation

The Model

showed

in Section 3 that individuals in

groups Tl and

TO

This specification

externalities

22

that

through a trickle-down

individuals in group

21

4,

did

fair.

4.2

We

=

ft)

TDA

and precisely estimated: a 10% increase

probability that an individual attends the fair

effect

who

can be estimated by running the IV

regression (2) on the sample of individuals not enrolled in the

U

who

letter.

a person receiving a letter can influence her colleagues

to the

with

TO but

only equally likely to enroll in the

are in the

is

group Tl are more

TDA

same departments and thus exposed

similar to that of

Acemoglu and Angrist

likely to

(1999),

fair

than

after the fair. Individuals in

to the

who

attend the

same network

seek to estimate

effects at

human

capital

on earnings.

The average L

is

not exogenous because

it is

computed over

September 2000).

14

all

employees (enrolled or not in the

TDA

by

the department

The only

level.

between the 7T and TO groups

difference

received the inducement letter and hence are

that the direct fair effect

is

zero for those

Reduced form evidence from Section

than individuals

phenomena can explain these

First, as individuals in

is

who

likely to

attend the

have attended the

fair

and to enroll

group TO are more

likely to

attend the

(compared to group

for

individuals)

is

measured

for the

for those individuals

treatment

effect of

TO

same population. The

who come because

the

attend the

fair for

fair just for

thus do not get

much out

This suggests

group TO are more

in the

TDA

afterward. Three

had a

than group

individuals,

positive effect

on their

latter effect is the

treatment

effect of

TDA

the

of the inducement letter while the former effect

those individuals

it.

it

group TO individuals

effect for

who

are induced to

It is

come

is

fair

the

to the fair because

plausible to think that individuals

the $20 might not be very interested in the content of the

of

likely

individuals) because these treatment effects

they have been influenced to attend by their colleagues.

who

fair.

not necessarily contradictory with the zero treatment effect

group Tl individuals (compared to group

are not

in

fair

important to note that this positive treatment

is

T\ individual

results.

plausible to think that for this group, attending the fair has

participation. It

that

because of the $20 reward.

fair just

showed that individuals

both to attend the

group

in

3 also

more

is

In contrast, individuals induced to

come by

fair

and

their colleagues

(with no financial reward) are likely to be more interested by the event and thus end up being

more

influenced

treatment

effect

by what they learn

We

at the fair.

will

develop and formalize this differential

below using the theory of Local Average Treatment Effects (LATE) developed

by Imbens and Angrist (1994), and Angrist, Imbens, and Rubin (1996).

The second reason why group TO

individuals

is

individuals are

that, because of our experiment,

and individuals may be influenced by

could influence

TDA

social

more

likely to enroll in the

T departments

network

effects.

TDA

We

assume, however, that only

start enrolling in the

TDA.

fair

attendees

who

Peer effects within departments

who

are not enrolled in the

Individuals already enrolled in the

TDA

who

attend the

decides to enroll in the

TDA, can

fair

fair.

TDA

induce their colleagues to

presumably influence

through the second channel and not through the information collected at the

15

departments

with their colleagues and thus increase the

23

Second, an individual

enrollment rate in their department.

23

are different from

enrollment through two channels. First, individuals

might share the information obtained on the

TDA than group

their colleagues directly

might also discuss her decision with colleagues, and induce some of them to enroll as

Third and more subtle,

it is

conceivable that, even for an individual

well.

who would have come

to the fair with no external inducement, receiving the letter offering the $20 reward modifies her

psychological motivation for attending the

the

fair,

she might convince herself that she

really interested in the content of the fair.

but there

is

of rewards.

and

This literature

and Cooper

incentives for acting as

if

direction than providing

Lepper

et al. (1973)

.

This type of

just for the $20

effect is

now paid

to attend

and thus that she

not

is

not standard in economic models

These

is

summarized

in

Ross and Nisbett (1991) (pp. 65-67). Festinger

(1978) showed that providing people with small financial

et al.

they hold a given belief promotes greater change in the "rewarded"

them with

large incentives. Perhaps

most

closely related to our setting,

showed that school children who are rewarded to play with magic markers

are less likely to enjoy

"work"

coming

is

is

substantial evidence in the psychology literature on the motivational consequences

(1959)

al.

Because the individual

fair.

it

than children

who

are not, as

results generated a substantial

amount

if

"play" had subjectively turned into

of interest because they

go against the

conventional reinforcement theory that would appear more intuitive.

These three

effects,

namely the

differential treatment effect, the social

network

and

effect,

the motivational reward effect can be captured the following simple linear model as follows.

Let us assume that

i

fair

attendance increases the probability of

by 71 Let us denote by y % the

.

dummy

TDA

participation of individual

for individual participation in the

TDA. We

posit the

following specification

i

y

The

fact that 7*

treatment

effect.

The

the treatment effect

social

network

/*

effect

is

Finally, the motivational

-y

1

is

+ l7+ti*.

(4)

captured by the average

reward

effect

fair

participation rate /

can be captured by assuming that

potentially (negatively) correlated with the letter treatment

order to simplify the presentation,

It

i

can vary from individual to individual captures the potentially differential

in the department.

24

=7

let

.

In

us assume that -f takes to following simple form

would be possible to develop a more general non-linear model but

strategy and interpretation. Therefore,

U

we consider only the simple

16

linear

this

would not change our estimation

framework.

.

= 7& -

7*

where 75

is

independent of L

the motivational reward

assuming that v

=

!

(this is the

and thus that

attendance on

outcomes

fair

7'

TDA

literature

we observe only one

on

differential

independent of

is

enrollment,

effect

amounts

to simply

V

In order to define treatment

0.

useful to introduce the notion of potential

it is

i,

had he been

treatment

1 Monotonicity

in

group Tl, TO, or

0.

Obviously, for each

As the

of the three potential outcomes for fair attendance.

effects

has recognized (see Imbens and Angrist (1994)), in

order to be able to identify parameters of interest,

Assumption

component), and v represents

effect

of the groups Tl, TO, or

attendance decision of individual

i,

standard treatment

For each individual, we denote by /'(Tl), /'(TO), and /'(0) the

for fair attendance.

individual

(5)

Assuming no motivational reward

effect.

Each individual belongs to one

effects of fair

vL\

we need

make

to

Assumption: for each individual

the following assumption:

/'(Tl)

i,

>

/'(TO)

>

/'(0).

This assumption states that receiving the letter can only encourage individuals to attend the

fair

(and in no case deter them), and that having one's colleagues receive the letter can also only

encourage an individual to attend the

fair (relative

to the situation where no colleagues receive

the letter). This assumption sounds very plausible in the situation

we

analyze.

The Monotonicity

assumption implies that the population can be partitioned into four different types.

First, the never takers are individuals

=

such that /'(Tl)

/'(TO)

=

/'(0)

=

0.

These

individuals do not attend the fair and would not attend regardless of the group to which they

belong. Second,

1

>

/'(TO)

financial

/'(0)

define the financial reward compliers type as individuals such that /'(Tl)

=

0.

These individuals attend the

=

/'(TO)

=

1

>

/'(0)

department receives the

=

only

if

they receive the

These individuals would not attend the

0.

letter,

but attend the

(whether or not they themselves receive the

individuals such that /'(Tl)

of the

fair

letter

=

with the

reward promise. Third, we define the social interaction compliers as individuals such

that /'(Tl)

in their

=

we

=

/'(TO)

=

/'(0)

letter).

=

1.

group to which they belong.

We make

the following additional assumption.

17

fair if

fair if

nobody

they are in a treated department

Finally,

we

define the always takers as

These individuals attend the

fair

regardless

.

Assumption

2 Exclusion restriction assumption: u l

The assumption

means that the

letter inviting the

decisions of those

fair

that the error term

attendance).

who do

25

The

we

is

fair

To

assess the extent to

appendix).

There

is

no

assignment status

has no direct

effect

on

fair

its effect

sent did not mention

TDA

TDA

but only benefits in general, and

status (see the facsimile in appendix).

TDA

significant difference in

we send the

affect decisions,

TDA

participation after 6

status (see

months between

departments to which we sent the questionnaire and departments to which we did not (the

ference

is

dif-

actually negative at -0.093 percentage points with a standard error of 1.3 percentage

Within departments to which the questionnaire was

points).

l

TDA participation

which asked detailed questions about

2,

L

on individual and departmental

which written communication could

questionnaires described in section

U

letter

(beyond

did not contain any mention of the employee's

independent of

independent of the

employee to the

not attend the

letter

ul

is

sent, the difference

is

only 0.90

percentage points (with a standard error of 0.94 percentage points) and not statistically significant either. Therefore, the targeted questionnaire

participation to the

TDA.

It is

thus

is

who

sent

that employees

no more

did not

seem to

TDA

affect individuals'

Assumption

1,

a

fair

enrollment. This echoes the results in Choi et al

two versions of a questionnaire to randomly selected employees, and found

who

likely to

TDA

plausible to think that, as stated in

invitation letter does not directly affect

(2001a),

on

received a questionnaire with

subsequently enroll in the

more questions about retirement savings were

TDA

than those who received a version without

those questions. 26

Taking the average of equation

(4)

over groups

Tl and TO, and taking the

difference,

we

obtain

yT1

-

y T0

=

E\y'\T\]

- £[y

2

|T0]

= E\^s f - vf + Tf + u

Using the exclusion assumption stating that u r

is

l

\Tl]

- E[Ys f + Tf +

u*\T0}.

independent of L*, we have

yTi-yro = E\^ {f{T\) - f(T0))} - vE[f\T\].

5

However note that assumption

those

who attended the

fair,

1

does not rule out the possibility that the letter can affect the

by reducing the

fair's effectiveness

(through the motivational reward

TDA

effect

status of

described

above)

"

This

is

also evidence that information

conveyed through mailing

18

may

not have a great impact on final decisions.

Using the monotonicity assumption, we then obtain

VTi

~

= E{fs \f(Tl) - f (TO) =

Vto

As P{f(Tl)

=

1)

= hi

1

and P{p{Tl)

~

f

f°

JT\ — JTO

Thus comparing

individuals

-/

1]

l

T(f (Tl) -

•

(T0)

= E[fs \f(Tl) -

=

/'(TO)

= fn -

1)

/'(TO)

=

1]

=

/to,

we

individuals

TO

-

-

(6)

.

- JTO

sum

provides an estimate of the

of the direct

average treatment effect for financial reward compilers and the motivational reward

effect.

that the social network effects (term Tf) cancel out in the comparison of groups

because they are

common

Individuals in group

in

TO and

effects,

TO do

TO

individuals in

effect involved in this

over groups

TO and

y T0

0,

Tl and TO

do not receive the inducement

individuals in group

TO. As none of the individuals in groups

reward

Note

to both groups.

but some of the peers of individuals in

because of network

1)

finally obtain

/T1

-„

JT1

T\ and

- uP(f(Tl) =

1)

receive the letter.

are

more

TO and

As we have seen

attend the

likely to

fair

receive the letter, there

is

letter

in Section 3,

than individuals

no motivational

comparison. More precisely, taking the average of equation

and taking the

difference,

-go = Etf\T0] - E\y

l

\0]

(4)

we have

= E\Y(f(T0) - f(0))}+T\fT -

/„].

Hence, we finally obtain

vto

JTO

-yo =

— 70

Thus comparing group TO

treatment

Our

to group

effect for social interaction

analysis has

treatment

E tf\fi {T0) _ r (0) =

+r

.

fr ~ fo

JTO

-

provides an estimate of the

(7)

JO

sum

compilers and the social network

shown that there are

effect for financial

i]

of the direct average

effect.

four parameters of interest in the model: the average

reward compilers, the average treatment

effect for social interaction

compilers, the social network effect parameter T, and the motivational reward effect v.

experiment provides us with only two instruments

identify

all

four parameters together.

these four parameters can

Only

if

L and

l

D

l

,

thus

it is

clear that

we

Our

cannot,

we make additional assumptions about two

we estimate the remaining two parameters. In the next

19

subsection,

of

we

discuss three alternative assumptions under which the remaining parameters of the

be estimated.

is

proceed not with the intention of claiming any particular set of assumptions

correct, but rather to explore the implications of each assumption.

Interpretation under Alternative Identification Assumptions

4.2.2

•

We

model could

No

motivational reward and no social network effects

In that situation, both parameters

T and

v are equal to zero, and

we can

identify both

average treatment effects for financial reward compilers and social interaction compilers. Under

these assumption, equation (6) reduces to:

V

~

f

P

JT\ ~ JTO

1

Thus, the average treatment

IV regression

of

TDA

departments using

U

effect for financial

enrollment on

JTO

of

TDA

enrollment on

-

fair

=E[ 1

i

i

\f

(T0)-f

i

(0)

we have

=

l}.

months and 11 months

and

(9)

JO

compliers can be obtained by an

attendance on the sample of individuals

(2)

(8)

attendance on the sample of individuals in treated

effect for social interaction

an instrument. Column

4.5

fair

1].

reward compilers can be obtained by a simple

as an instrument. Similarly, using (7),

yT°- yo

The average treatment

= EtflfiTl) - f (TO) =

(3) in

in

TO

or

Table 4 present these IV estimates,

after the fair.

IV

regression

groups using

for

TDA

D

%

as

enrollment

Consistent with the reduced form evidence, the IV

estimates suggest a positive treatment effect on social interaction compliers, and no effect on

financial

reward compliers. The results

in

column

(3)

can be thought of as an upper bound on

the effects of the fair itself for the population of social interaction compliers. These individuals

are not affected

in

(9)

by the motivational reward, but

would be an upper bound of the direct

if

peers effects are present, the

effect of the fair.

IV estimate

This upper bound

is

13.5

percentage points after 4.5 months, and 14.8 percentage points after 11 months. These effects

are of comparable size (slightly higher) than those estimated

by Madrian and Shea (2002)

non-experimental set-up.

•

Constant Treatment Effects with no motivational reward

20

effect

in a

If

there

is

no motivational reward

same across individuals and equal to

and equation

are identified

=

7,

and the standard treatment

the

both parameters, 7 and T of the structural equation

(4)

0)

reduces to

(6)

7

§^f°=

JT\ ~ JTO

This ratio

is

(10)

.

the IV estimate presented in column (2) in table

Therefore, under these restrictive assumptions,

is

we can conclude

4,

which we discuss above.

that the direct effect of the

=

Therefore the overall effect of

(7

fair

-

+ r)/ + u,

yT

attendance on

TDA

(7

fair

and T, we obtain

zero for everyone. Taking the average of equation (4) over departments

yo

effect 7'

is

effect (u

+ r)/r + «•

(n)

participation, taking into account

all

the

social effects, is the ratio

=7+

f^f

It -

r.

(12)

Jo

This overall effect of one additional person attending the

the direct causal effect 7 of the

fair,

and the

months and

(for participation after 4.5

made

here, the difference of

The implied

•

estimates of

T

columns

(1)

are 10.14%

social effects

after 11

In both cases, the overall effect of the

4.

(2) gives

and 6.7%,

on

TDA

T from equation

and

after 4.5

and

11

T =

0.

who

the

sum

of

These estimates

(4).

an estimate of the social

In this case, the standard treatment effect 75 (for those

(7), since

is

(1) in table

Under the assumptions

significant.

Constant Treatment Effects and no social network

be obtained directly from

participation

months) are presented in column

fair is positive

and

fair

months

effect

parameter.

respectively.

27

effects

did not receive the letter) can

In turn, equation (6), with the

75, can be used to recover v. Using the estimates of fri, and fro from table

first

2,

term

set to

we obtain an

estimate of v of 0.0927 after 4.5 months, and 0.0620 after 11 months. Under these assumptions,

receiving the letter reduces the treatment effect of the fair by

4.5

2

months, and 42%

for

TDA

69%

for

TDA

participation after

participation after 11 months.

'Estimates of the direct and social effects parameters (and their standard errors) can also be directly obtained

by an IV estimation of equation

(4)

(where 7

1

=

7), using -D,

21

and L, as instruments.

The

distinction between differential treatment effects, social network effects,

tional reward effects

apart.

Thus,

it

is

is

clear conceptually but our experiment does not allow us to tell

useful to describe

needed to separate these

is

a

a

first

what type

effects. Differential

of alternative experimental designs

them

would be

treatment effects arise in our setting because there

stage in our experiment where individuals decide whether or not to attend the

result, only a self-selected fraction of individuals attends the fair. Motivational

arise

and motiva-

because individuals receive a monetary payment

attending the

for

fair.

reward

As

effects

fair.

Social network effects could be identified with the following experiment. Within a subsample

of the "treated" departments, a

subsample of employees would

all

attend automatically an

information session. This could be done by making attendance a job requirement of employees.

One

could then test whether the

TDA

among

participation rises

relative to that of individuals in untreated departments.

the colleagues of the treated

Motivational reward effects could be

estimated by paying people for attending an information session in a situation where everybody

is

supposed to attend.

For example, in

information sessions about benefits.

In

many

new

firms,

some departments,

presented as a normal process through which

all

hires are often invited to attend

this information session could

new employees

go.

be

In other departments,

attending this information session could be presented as voluntary but a financial reward could

be offered

for

attendance (large enough to induce virtually everybody to attend).

If

everybody

attends in both cases, the average treatment effect would be expected to be the same in both

groups in the absence of a motivational reward

effect.

28

Evidence of differential treatment

effects

could potentially be obtained by using non-monetary incentives of various intensity to attend the

fair.

fair.

For example, some employees could be sent a letter simply reminding them of the benefits

Others could be sent a more pointed

be obtained

at the fair.

person to attend the

fair.

groups of compilers and

28

in

Note that

this setting

One

them that important information can

could also use emails, personal phone

These

may

letter telling

different

calls or

even remind them in

encouragement designs are associated with