MA ^- Room ^

advertisement

'

OEWEVi)

•""""

MIT LIBRARIES

ff-6S\

/V^^lS

no

3 9080 03317 5826

^- ^

(

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

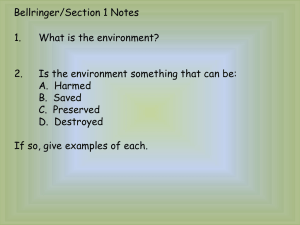

Nudging Farmers

to

Use

Fertilizer:

Theory and

Experimental Evidence from Kenya

Esther Duflo

Michael Kremer

Jonathan Robinson

Working Paper 09-19

June 26, 2009

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 02142

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://ssrn.com/abstract=1 427446

Nudging Farmers

to

Use

Fertilizer:

Theory and Experimental Evidence from Kenya

Esther Duflo. Michael Kremer, and Jonathan Robinson'"

June 26, 2009

While many developing-country policymakers see heax'y fertilizer subsidies as critical to

raismg agricultural productivity, most economists see them as distortionary, regressive,

environmentally unsound, and argue that they result in politicized, inefficient distribution of

fertilizer supply. We model farmers as facing small fixed costs of purchasing fertilizer, and

assume some are stochastically present-biased and not fully sophisticated about this bias.

Even when

relatively patient, such fanners

until later periods,

many

when

they

may

may

procrastinate, postponing fertilizer purchases

be too impatient to purchase

fertilizer.

Consistent with the

Western Kenya fail to take advantage of apparently profitable

do invest in response to small, time-limited discounts on the

cost of acquiring fertilizer (free delivery) just after har\'est. Later discounts have a smaller

impact, and when given a choice of price schedules, many farmers choose schedules that

model,

farmers

in

fertilizer investments, but they

induce advance purchase. Calibration suggests such small, time-limited discounts yield

higher welfare than either laissez faire or heavy subsidies by helping present-biased fanners

commit

to fertilizer

overuse

fertilizer.

'

The authors

use without inducing those with standard preferences to substantially

are respectively

from

MIT

(Department of Economics and Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action

Lab (J-PAL)); Harvard, Brookings, CGD, J-PAL, and NBER; and

Ikoluot,

Edward Masinde, Chris Namulundu,

Evite Ochiel.

UC

Santa Cruz and .T-PAL.

We

thank John

Andrew Wabwire, and Samwel Wandera,

outstanding fieldwork, Jessica Cohen, Anthony Keats, Jessica Lemo,

Owen

Ozier, and Ian

Tomb

for

for excellent

research assistance, and International Child Support (Kenya), Elizabeth Beasley and David Evans for work

setting

up the

project.

We

thank Abhijit Banerjee for his persistent encouragement and

many extremely

helpful

conversations, as well as Orley Ashenfelter, Pascaline Dupas, Rachel Glennerster, and seminar participants

Arizona, Berkeley, Brown,

and the

"New

Products

in

EBRD, LSE, Nonhwestem, Pompeu

Microfmance" conference

at

UCSD

Fabra,

for

UCLA, UCSD, USC,

comments.

the

at

World Bank,

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/nudgingfarmerstoOOdufl

"The

of the world

rest

to

it

is

fed because of the use of good seed and inorganic fertilizer, full

has not been used

stop. This technolog}'

get access

is

give

it

in

most of Africa. The only way you can help farmers

away free or subsidize

it

"

heavily.

-

<-

•

--

Stephen Can; former World Bank specialist on Sub-Saharan Afi'ican agriculture, quoted

Many

-...•.-,

.-..,.,..-

Dugger,2007.

agricultural experts see the use of

,,,..

modem

.

,

,

.,,

,.-........'

,

,

inputs, in particular fertilizer, as the

agricultural productivit}'. Pointing to the strong relationship

in test plots,

......

between

fertilizer

in

key

to

use and yields

they argue that fertilizer generates high returns and that dramatic growth in

agricultural yields in Asia

and the stagnation of yields

in

'

;

Africa can largely be explained

by

increased fertilizer use in Asia and continued low use in Africa (Morris, Kelly, Kopicki, and

Byerlee, 2007). Based on this logic, ElHs

subsidies.

Many governments

amounted

fertilizer subsidies

( 1

992) and Sachs (2004) argue for

have heavily subsidized

to 0.75

percent of

fertilizer

fertilizer. In India, for

GDP m

•'

example,

•

1999-2000 (Gulati and Narayanan,

2003). In Zambia, fertilizer subsidies consume almost 2 percent of the government's budget

(World Development Report. 2008).

In contrast, the

presumption

that

levels.

'

.

tradition associated with Schultz (1964) starts with the

farmers are rational profit maximizers, so subsidies will distort

away from optimal

beyond

Chicago

'

Others have argued that

these Harberger triangles.

They

fertilizer

use

fertilizer subsidies create large costs

are r)'pica!!y regressive as wealthier farmers and

those with more land often benefit most from subsidies (Donovan, 2004), and loans for

fertilizer often

moderate

go

to the politically

fertilizer

use

is

may

rates.

Moreover, while

environmentally appropriate, overuse of fertilizer induced by

subsidies can cause environmental

subsidies

connected and have low repayment

damage (World Bank, 2007). Furthermore,

fertilizer

lead to government involvement in fertilizer distribution, politicization, and

very costly failures

to

Partly due to the

supply the right kind of fertilizer

at the right time.

dominance of the anti-subsidy view among economists and

international financial institutions, fertilizer subsidies have been rolled back in recent

decades. Recently, however, they have seen a resurgence. For example, after Malawi's

removal of fertilizer subsidies was followed by

subsidy on

fertilizer.

a

famine, the country' reinstated a two-thirds

This was followed by an agricultural

boom which many,

including

Jeffrey Sachs, attribute to the restoration of the fertilizer subsidies (Dugger, 2007).

'•

A

key assumption

would use

in the

Chicago

tradition case against fertilizer subsidies

the privately optimal quantity of fertilizer without subsidies.

from

To

is

that

reconcile low

use found in agricultural research

fertilizer

use with the large increases

stations,

economists often note that conditions on these stations differ from those on

may

world farms, and returns

be

in yield

much lower

fertilizer

in real conditions,

other inputs optimally. There

is

irrigation, greater attention to

weeding, and other changes

may have

trials

evidence that

difficulty in implementing.

with farmers on their

low. Those

trials

showed

of 36 percent over

own farms

that

when

in a

used

we implemented

Kenya where

in limited quantities,

season on average, which translates

a

in agricultural practice that

region of Western

fertilizer is

where farmers cannot use

previous work

in

real-

complementary with improved seed,

fertilizer is

However,

fanners

a series

fertilizer

it

fanners

use

of

is

generates returns

70 percent on an annualized basis

to

(Duflo, Kremer, and Robinson, 2008), even without other changes in agricultural practices.

Low

is

investment rates

in the face

well-known and long-used

m

of such high returns are particularly puzzling since fertilizer

the area.

Moreover, since

fertilizer is divisible,

standard

theory would not predict credit constraints would lead to low investment traps in this

context.' There could of course be fixed costs in

example, making a

important role

in

trip to the store).

buying or learning

use fertilizer (for

to

Indeed, small fixed costs of this type will play an

our model. However, such costs would have to be implausibly large to

justify the lack of fertilizer investment in the standard model."

In this paper

we

argue that just as behavioral biases limit investment

financial investments in pension plans

and Madrian, 2008), they

developing countries.

We

may

by workers

in the

United States

simple model of biases

In the

model some farmers are

when

odds

'

As discussed below,

profits are

fertilizer to

literature (see

that they will

they are patient today. Going

and perhaps deciding what type of

by farmers

in

O'Donoghue

(stochastically) present-biased and at least

partially naive, systematically underestimating the

future, at least in the case

Choi, Laibson

farmer decision-making inspired

in

by models of procrastination from the psycholog\' and economics

and Rabin, 1999).

(e.g.,

limit profitable investments in fertilizer

set out a

in attractive

use and

concave rather than convex

to the store,

how much

in fertilizer

since farmers always have the option of applying fertilizer intensely on

be impatient

to

buying

in the

fertilizer,

buy, involves a

utility

use per unit of land area. Moreover,

some

land while

leavmg other pieces of

land unfertilized, returns must be non-increasmg.

"

For instance, consider

fertilizer takes

a

farmer with an hourly wage of SO.

one hour and

who

can only

initially afford $1

1

3

over for

worth of

whom

round

fertilizer.

trip travel to

town

to

buy

Since half a teaspoon of top

Even

cost.

if this

cost

is

small, so long as farmers discount future utility, even farmers

plan to use fertilizer will choose to defer incurring the cost until the

they expect to

still

being impatient

be willing

to

purchase the

period

in the last

in

fertilizer later.

which buying

is

last

moment

who

possible, if

However, farmers who end up

possible will then

fail to

invest in

fertilizer altogether.

Under

the model,

heavy subsidies could induce

fertilizer

use by stochastically hyperbolic

farmers, but they also could lead to overuse by farmers without time consistency problems.

The model implies

that if offered just after har\'est

(when fanners have money)

small, time-

limited discounts on fertilizer could induce sizeable changes in fertilizer use. In particular,

early discounts of the

same order of magnitude

purchase can induce the same increase

m

fertilizer

of magnihide of the out-of-pocket costs of

(before the harvest)

to

have an option

to

as the psychic costs associated with fertilizer

to

Moreover, ex ante

to fertilizer use.

(NGO), we designed and

tested a

randomized design, we compared the program

fertilizer subsidies or

larger discounts of the order

be eligible for the discount early on, so as

(Kenya) a non-government

In collaboration with International Child Support

organization

much

fertilizer later in the season.

some farmers would choose

commit

use as

reminders

to

use

program based on these predictions. Using

to alternative inter\'entions,

fertilizer.

The

such as standard

results are consistent with the

model.

Specifically, offering free delivery to farmers early in the season increases fertilizer use

to

60 percent. This effect

subsidy on

is

a

by 46

greater than that of offering free delivery, even with a 50 percent

fertilizer, later in the season.

Following an approach similar

to

O'Donoghue and Rabin

(2006).

we

use the model to

analyze the impact of different policies depending on the distribution of patient, impatient,

and stochastically present-biased farmers. Calibrations based on our empirical

that 71 percent

of farmers are stochastically present-biased, 16 percent are always patient,

and 13 percent are always impatient. This yields

farmers should never use

fertilizer in the three

a prediction that

seasons

percent of comparison farmers do not use fertilizer

have

data.

The

calibrated

proportion of farmers

like to

results suggest

be offered free

in

we

take up fertilizer

follow them. Empirically, 52

any of the three seasons for which

model matches other moments

who

roughly 55 percent of

when given

we

in the data, in particular the

the choice of

which date they would

fertilizer delivery.

dressing fertilizer yields returns of 36 percent over a season, netting out the

lost

wages would leave

the famier

with a 23 percent rate of return over a few months.

3

The

calibration suggests that a "paternalistic libertarian" (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008)

approach of small, time-limited discounts could yield higher welfare than either laissez faire

policies or

heavy subsidies, by helping stochastically hyperbolic farmers commit themselves

to invest in fertilizer

m fertilizer use

while avoiding large distortions

among

time-consistent

farmers, and the fiscal costs of heav>' subsidies.

The

rest

of the paper

on agriculture and

is

strucmred as follows: Section 2 presents background information

fertilizer in

Western Kenya. Section

testable predictions. Sections 4 lays out the

results,

presents the model and derives

3

program used

to test the

model; Section 5 reports

and Section 6 calibrates the model and then uses the calibrated model

welfare under laissez

faire,

compare

heavy subsidies, and small time-limited subsidies. Section

examines alternative hypotheses, and Section

for realistically scaling

to

8

7

concludes with a discussion of the potential

up small, time-limited subsidies

in a

way

that

would not involve

excessive administrative costs.

2.

Background on

Our study

area

is

Fertilizer use in

Western Kenya

a relatively poor, low-soil fertility area in

Western Kenya where most

farmers grow maize, the staple food, predominantly for subsistence. Most farmers buy and

sell

maize on the market, and store

it

at

home. There

are

two

agricultural seasons each year,

the "long rains" from March/April to July/August, and the less productive "short rains"

July/ August until December/Januar}'.

;,

.

from

;.

Based on evidence from experimental model fanns (see Kenyan Agricultural Research

Institute, 1994), the

seeds.

Di-Ammonium Phosphate (DAP)

Nitrate

one

to

Kenyan Ministry of Agriculture recommends

(CAN)

fertilizer at top

two months

(and occasionally

typical farmer

is

in local

a

and Calcium

fertilizer at planting,

dressing (when the maize plant

is

Ammonium

knee-high, approximately

after planting). Fertilizer is available in small quantities at

would need

Although there

that farmers use hybrid

market centers

shops outside of market centers). Our rough estimate

to

walk for roughly 30 minutes

market for reselling

fertilizer,

to

is

that the

reach the nearest market center.

not very' liquid and resale involves

it is

substantial transaction costs.''

Experiments on actual farmer plots suggest low, even negative returns

combination of hybrid seeds and

"

fertilizer at planting

and top dressing, (Duflo, Kremer, and

Discussions with people familiar with the area suggest reselHng

approximately 20 percent of the cost of

to the

fertilizer typically

fertilizer in addition to the search costs

involves a discount of

of finding a buyer.

4

Robinson, 2008), although

it

is

plausible that returns might be higher if farmers changed

other fanning practices. Similarly, the use of a

dressing

is

full

teaspoon of

not profitable, because farmers realize large losses

and seeds do not germinate. However,

teaspoon of

fertilizer

just

more conservative

per plant as top dressing, after

it is

when

per plant as top

rains fail or are

delayed

strategy of using only one half

clear that seeds have germinated,

much of the downside

yields a high return and eliminates

sample plants

a

fertilizer

risk.

The average farmer

in

our

under one acre of maize. Using one half teaspoon of fertilizer per plant

increases the yield by about $54 per acre and costs $40 per acre, a 36 percent return over the

several

basis)

months between

the application of fertilizer and harvest (70 percent

on real-world farms even

on an annualized

absence of other complementary changes

in the

in

farmer

behavior.

The incremental

valued

approximately $18 per acre, corresponding to a negative return of around -55

percent

at

at full price,

return to the

first

yield associated with the second half teaspoon of fertilizer

but a 30 percent return under a two-thirds subsidy, very close to the

half teaspoon at

full price.

However, despite these large potential returns

as top dressing, only

40 percent of farmers

and only 29 percent report using

program.''

When

asked

why

in

in at least

it

they do not use

unprofitable, unsuitable for their

our sample report ever having used fertilizer

one of the two growing seasons before the

farmers rarely say fertilizer

trials

we

money

to

purchase

it.

Of farmers

conducted, only 9 percent said that

unprofitable while 79 percent reported not having enough money. At

to take at face value: fertilizer

can be bought

proceeds would eventually yield sufficient money

Even poor farmers could presumably

from consumption

One way

to fertilizer

to reconcile farmers"

is

first this

interviewed

was

fertilizer

seems

difficult

small quantities (as small as one kilogram)

in

and with annualized returns of 70 percent, purchasing

har\'esl

fertilizer

or too risky: instead, they overwhelmingly reply that

soil,

before the small-scale agricultural

applying limited quantities of

to

fertilizer,

they want to use fertilizer but do not have the

entire plot.

is

to

a small

amount and

in\'esting the

generate sufficient funds to fertilize an

reallocate

some of the proceeds of their

investment per acre.

claims that they do not have

money

to

buy

fertilizer

with

the fact that even poor fanners have resources available at the time of han'est

is

may

follow through

initially intend to

on those

save in order

to

purchase

plans. In fact, 97.7 percent of fanners

These figures

differ slightly

from those

ir.

fertilizer later but

who

then

fail to

that farmers

participated in the demonstration plot

Duflo, Kremer. and Robinson (2008) because the sample of famiers

differs.

5

program reported

that they

planned

to

use

fertilizer in the

following season. However, only

36.8 percent of them actually followed through on their plans and used fertilizer in the season

which they said they would. Thus,

in

use

have no money

fertilizer often

appears that even those

it

to invest in fertilizer at the

planting or top dressing, several months

who

time

are initially planning to

it

needs

to

be applied, for

later.

Model

3.

Below we propose

of many workers

in

a

model of procrastination similar to those advanced

developed countries

to take

(O'Donoghue and Rabin, 1999) and derive

to

explain the failure

advantage of profitable financial investments

testable predictions. In the model,

are present-biased, with a rate of time preference that

is

When

all

they are very present-biased, fanners

consume

moderately present-biased, farmers make plans

to

use

some farmers

realized stochastically each period.

they have.

fertilizer.

When

But early

they are

in the season,

patient farmers overestimate the probabilit)' that they will be patient again, and thus they

postpone the purchase of fertilizer

to

a

be impatient, they consume

all

until later,

in cash instead. Later, if they turn

of their savings instead of investing in

lower usage of fertilizer than the farmer

3.1

and save

in the early

out

fertilizer, resulting in

period would have wanted.

Assumptions

Preferences and Beliefs

Suppose

that

some

fraction of farmers

exponentially discount the future

A

proportion

d) is

').

are patient.

They

are time consistent

and

at rate pi^.

(stochastically) present-biased, and systematically understate the

extent of this present bias. In particular suppose that in period k\ these farmers discount every

future period at a stochastic rate pk (for simplicity

between future periods).

=

In

each period

-

/.-,

we assume

that there

is

with some probability p, the fanner

fanner

is

quite impatient {6k

Furthermore, while fanners do recognize that there

is

a

(/3i.

pfi),

and with probability

(

1

no discounting

p), the

=

is

fairly patient

Pl).

chance that they will be impatient

in

the future, they overestimate the probability that they will be patient. Specifically, the

probability that a patient farmer believes that she will

There are several ways

still

to interpret this stochastic rate

be patient

in the future is

of discount.

One

p

>

p.

interpretation

is

that farmers are literally partially naive about their hyperbolic discounting, as in the original

O'Donoghue and Rabin (1999) framework. An

Banerjee and Mullainathan (2008a),

(e.g., a party) that is

farmer

A

tempting

that a

is

farmer

to the

of

alternative interpretation, along the lines

consumption opportunity occasionally

in that period, but

which

arises

not valued by the

is

in other periods.

final

proportion

one of these three

i"

are alwcn's impatient so that

tj^pes so

Finally, for simplicity',

^

+

+

(p

=

V'

we assume

(3k

=

Pl

in all periods. All

farmers are

1-

per-period

in that period, less a small utility cost associated

utility' in

any period

is

simply consumption

with shopping for fertilizer and the time cost

associated with deciding what quantity of fertilizer to buy, which will be described below.

Timing and Production

There are four periods. Period

to save,

which

consume

pre-commit

fertilizer in

period

period

those

who have

will later consider a situation

fertilizer pricing in this period.

make

m

We

choice of a pnce

a

0.

between consumption, purchase of fertilizer

that yields liquid returns

of

we

but later allow the fanner .to

the farmer harvests maize, receives

7,

The farmer does not plan

to the har\'est.

to different patterns

from period

will initially abstract

In

immediately prior

or purchase fertilizer in this period, but

the farmer can

schedule for

is

by the time

income

.t

>

and can allocate income

2,

for the next season, and a short-run investment

fertilizer

needs

Some

be applied.

to

farmers, such as

shops where they can use more working capital, will have high return

investments that yield liquid returns over

return investment opportunities.

proportion A of farmers, and low

We

a short period,

therefore

{R >

assume

0) for the rest.

whereas others

R

the net return

Farmers know

will

is

have lower

high (/?) for a

their rate

of return with

certainty.

Fanners can choose

fertilizer

investment

to

to use zero,

keep the analysis tractable and

work, which examined the returns

However,

to zero, half or

to parallel

assume discreteness of

our previous empirical

one teaspoon of fertilizer per

plant.

the discreteness does not drive our results.

Let pfi denote the price of fertilizer

small

We

one or two units of fertilizer.

utilitv'

cost

period

1.

Purchasing any

/ (encompassing the time cost of going

well as deciding what type to use and

amount of fertilizer purchased. Note

assumption

in

that there

is

some

how much

to buy).

that while fertilizer

to the

shop

This cost

is

fertilizer also entails a

to

is

buy

the fertilizer, as

independent of the

a divisible technology, the

fixed cost of shopping for fertilizer

is

consistent with our

-

finding that few farmers use very small amounts of fertilizer

the beginning of period 2,

season, those

who have

if

invested in period

receive

1

1

+

i? for

Borrowing

cost of producing fertilizer

=

laissez-faire, pji

of the

each unit invested. Farmers

which

in

=

1.

We

<

7:1^1

1

and pf2

Define the incremental yield

assume

that the cost

cash

to

be easily traded

at

=

income

Y'iz),

of reselling

so.

=

pfo

where

=

=

|,

is

the

heavy government subsidies

as well as a small, time-limited

z

V'(l)

—

amount of fertilizer

i'(0)

and

Maize, on the other hand

is

is

=

j/(2)

fertilizer is sufficiently large to

any time. Empirically, maize

at local

at

1.

to fertilizer as j/(l)

impatient farmers from doing

converted

their

not possible.

is

will also consider the impact of

In period 3, farmers receive

We

consume by using

be one, so that under competition and

to

adopted by Malawi, under which p/i

r>'pe

subsidy

p/2

assumed

is

next

for the

they have sufficient wealth, purchase either one or two units of fertilizer

price p/2 per unit incurring co^r/if they do so.

The

use no

which can be thought of as the time of planting

receive no additional income during this period: farmers can only

savings and,

to either

of their crop.^

fertilizer or fertilize a significant fraction

At

— they tend

used.

Y{2)

-

V'(l).

discourage even

completely liquid and can be

much more

liquid than fertilizer and can

markets.

Assumptions on Parameters

;

^ye assume:

;....:

.,

.•:.-.

'^=

/3Hy{l)>l

+

1

''

<y(2)<i

.

'

'.

f

+ /3^f>0^yil)>l +

,.•

;

-

-

(1)

;

f

(2)

-

(3)

•

•

,

1

>y(2)

The

'

-

first

has

it

to

be purchased right away. The second implies that an

impatient farmer will prefer to consume

^

price

is

For instance,

it

now

not heavily subsidized, even

among

farmers

who were

and 30 percent use top dressing

use

:(4)

condition ensures that a patient farmer prefers using one unit of fertilizer to zero

units of fertilizer, even if

if the

.'

on their entire

if

rather than to save in order to invest in fertilizer

it

is

possible to delay the decision and shopping

not offered free delivery or subsidized

fertilizer in a

fertilizer,

given season, but over 75 percent of those

'

plot.

between 20 percent

who do

use fertilizer

costs of purchasing fertilizer to a future period, and even if the rate of return to the period

investment

is

fertilizer if

it

their period

The second condition

high.

is

heavily subsidized

at

use more than one unit

two-thirds the cost of fenilizer, whatever the return to

market price (and

that therefore

no farmers will want

and also implies that patient farmers will prefer

at full price),

heavy subsidy of two-thirds of the cost of fertilizer (note

at a

condition does not include the shopping cost / because the cost

any

buy

investment opportunity. The third condition implies that the second unit of

1

fertilizer is not profitable at the full

two units

also ensures that impatient farmers will

1

is

to

to

use

that the third

incurred

if

the farmer uses

and does not depend on the quantity used). The fourth condition implies that

fertilizer

impatient farmers will not use a second unit of fertilizer even with a heavy subsidy of two-

,,,,._.,

thirds the cost of fertilizer.

These conditions match our empirical evidence on the

et al.,

2008) since we find

incremental return

to the

that the return to the first unit

second unit

is

negative

at

of

rates of return to fertilizer (Duflo,

similar to the return to the

(who use

fertilizer

first

/5h(1

+

R) >

the period

1,

we assume

which implies

=z

Pf2

=

I:

/?'//

(1 -h /?)

1

that patient farmers

at

subsidized prices,

> IJdl{1 + R) <

1,

farmers with high returns always

pj2

=

i;

Malawi

time-limited discounts under which pji

<

1

Farmer Behavior Under

c)

laissez-faire,

consider farmer behavior under laissez-faire,

m

3.2

and

we

heavy subsidies of the type adopted

traditional

=

Laissez-faire (p/i

by assumption

(1), the

every period will always use one unit of

fertilizer in

that

that patient period

and 3.4

p^j

Under

which suggests

two-thirds subsidy

at a

make

investment while impatient fanners never do.

1

In subsections 3.2, 3.3,

Pf.^

unit at market prices,

without a subsidy) would be likely to use two units

Finally, for completeness,

that the

market prices. The assumptions are also

consistent with evidence that the incremental return to the second unit

is

and

fertilizer is high,

penod

2.

By assumption

impatient will never use

fertilizer.

p/2

=

fertilizer.

and pf2

who

All will save at rate

proportion

w

which

which

=

1.

1)

proportion n of fanners

(2), the

By

=

in

in

of farmers

R

are always patient in

in

who

period

1

and buy

are always

our other assumptions, they will not avail themselves of

the investment opponunit)', whatever the return.

Now

consider the problem of a stochastically present-biased farmer deciding whether

(and when)

to

buy

fertilizer.

problem of a farmer

in

To

period

2,

solve the model,

we work backwards, beginning

who must choose between consuming one

with the

unit, or investing

9

it

in fertilizer.

Assumption

in period 2 will

2 will not use

use

(1) implies that a

fertilizer.

Assumption

impatient in period

consumer, and

will

1

from saving

1

is at

in

to

purchase

period

1

.

First,

best Piyfl)

(2), is

fertilizer in

-

Now consider a

farmer

who

consuming everything today:

today.

the rest

By

do

it

in

in

period

period

2"!

—

x

is

assumption

Now.

who

then

2).

If a

1

—

is

smaller than

period

patient in period

1

is

it

be optimal, note

(the loss in

we assume

/

+

dnvi'^), while her utility

from buying

who

is

that /3l(1

utility cost

fertilizer

is

is

if

.?•

<

/?)

away, or plan

to

buying

\

+R

p),

2.

To

1

see that postponing

period

2,

her utility

is

in

investment and

+

/S/^.

Thus, waiting

is

optimal if

X

-

-i^^+1

Rearranging,

we

and thus purchases

'"

+/3«(y(T)-/)

=

0,

+ p/3«(y(l) -/) + (!- v)^H >

the right

is

(5)

1

-

p,

.T

-

1

-

/

+

/3Hy(l)

(6)

find that the farmer will wait if

cost of using fertilizer

'

•

,

.

/(1-P/3h) +

p

may

.•

1

•'

wait to

fertilizer in

ends up being impatient (which she believes will happen with probability

r -

and

she consumes everything

fertilizer right

farmer waits, ends up being patient

^

utility is

1.

higher than not buying.

of buying fertilizer until period

-

When

+

patient today has a sufficiently high subjective

'-

her

consumption

Investing in fertilizer today dominates

(which she believes will happen with probability

If she

from

farmer with a high return

best to wait, and thus realize the return on the period

that if the

the gain

1,

is

farmer ends up being patient

p^

2, for a

.

should a patient farmer buy the

farmer

who

the farmer's utility if she purchases one unit of fertilizer

(1), utility

1.

postpone paying the

fertilizer

patient

impatient in period

is

from period

probabilit}' of being patient again (and therefore a high probability' of

period

is

observe that a farmer

/u./ (if the

saving opportunity). This farmer will also not save since

consumes

farmer

will not save: seen

which, by assumption

fertilizer),

period

has sufficient wealth and

(2) implies that a

problem of a farmer

investing in one unit of fertilizer

in

who

fertilizer.

Now consider the

and buys

farmer

hand side

is

•

y^ >/3//(y(l)-l)(l-p)

equal

to /3//(y(l)

small enough that /?//(y(l)

-

-

1).

If

1) is larger

(7)

we assume

than /

+

that the utilir\'

-~-^, then the right

10

hand side of

the inequality

decline with p. but the right hand side

hand side (which

the right

(0,1) such that for every

invest in the

easy

the

first

to see that

more

For p

steeper.

=

Both sides of the inequality

1,

the left

equal to zero). Thus, for each R, there

is

p > p*iR),

a

p'(R]

it

is

is

farmer

who

hand

side

a p'(/?) in the interval

is

intending to use fertilizer later prefers to

is

fanners will not save

it

is

2. It is

investment,

1

for the farmer to wait.

in

we assume

any case,

it

that

p

>

p*{R). Note that since impatient

not necessan,' that they believe they will be

is

patient in the future than they are in the present for this procrastination

Instead,

larger than

is

decreasing with R: the higher the return to the period

For the remainder of the model,

1

is

side.

period investment opportunity, and plans to buy fertilizer in period

more valuable

period

hand

larger than the left

is

problem

to arise.

only necessary that patient farmers overestimate the probability that they will

continue to be patient in the fuaire. This tendency to believe that future tastes will more

closely resemble current tastes than they actually will, termed "projection bias," has found

considerable empirical support (Loewenstein. O'Donoghue. and Rabin, 2003).

3.3

Farmer Behavior Under Malawian-StA le Heavy Subsidies

One

potential

way

buy two

pjo

=

j)

address underinvestment in fertilizer would be through heavy,

to

Malawian-sty'le subsidies. Under heavty subsidies, by assumption

patient will

=

(p/i

units of fertilizer,

and by assumption

(2),

farmers

(3),

who

farmers

who

are

always

always

are

impatient will buy one unit.

To

solve for the behavior of the stochastically impatient farmers

work backwards from period

in

2.

Assumption

period 2 will use one unit of fertilizer

(2) implies that

if ;>/2

=

|,

impatient farmers will not want to use two units of

penod

2 will thus purchase exactly

purchased

Now

purchase

it

again

even fanners who are impatient

while assumption (4) implies that

fertilizer.

A

unit if he has the wealth

farmer

do

to

who

it

is

impatient in

and has not already

consider the case of a stochastically hyperbolic farmer deciding whether to

fertilizer in

units. Recall that

penod

we

earlier.

period

(3) implies that a patient

two

one

in this case,

1

.

First consider a

farmer wants

it is

farmer

to either

who

patient

is

m period

1

.

.Assumption

purchase two units, or save enough

efficient for farmers to

purchase

all

of their

fertilizer

m

to

buy

a single

since by doing so they only need to pay the shopping cost of fenilizer once.

If a

fanner buys two units of

fertilizer

immediately, her

utility is:

11

.

.T.-^-f +

If the

farmer instead plans

she

if

impatient in period 2 she will purchase only

-

Thus, she will prefer

save and plan

+

3^^^;^^^

By

if

>

;;

reasoning similar

p*'(R). farmers

unit.

1

to the

who

/(I

-

to

R

at return

py(2)

+

however, she

If,

> pH{y{2)

-

(1

fertilizer later

utility

from waiting

P)^]

is:

(9)

if:

(10)

jfiR) such

a threshold

is

will wait until period 2 to

I

is

-Iki-p)

case without a subsidy, there

are patient in period

for future fertilizer use,

Thus, her expected

-/+

buy

M

(8)

patient in period 2.

is

^(^-^ + /3//b(i)

to

yil))

use fertilizer and saves

to

she will purchase two units of fertilizer

^

+

B„{y{2)

purchase

that

(it is

also easy to see that the threshold decreases with R, so those with higher returns to

investment

in

period

1

more

will be

p'(B). However,

values, f>"{R) could be smaller or larger than

the second unit of fertilizer at the subsidized price

on the

first unit

than p'{B].

of

Below we assume

scenario for hea\7 subsidy;

who

are patient in period

overusing

if

that

p

is

if

the

mcremental renim of

greater or equal to the incremental return

(i.e.,

3y(2)

>

v/(l)),

above both thresholds. Note

then p**(/?)

is

larger

that this is the best case

p was lower than p*'{R), the stochastically impatient farmers

would

1

is

an unsubsidized price

fertilizer at

Depending on parameter

likely to defer purchases).

all

buy two

units in period

1,

and thus would

all

end up

fertilizer.

Now, consider

a stochastically patient fanner

Given our assumptions, she wants

to

who happens

and she will postpone

this plan.

buymg

be impatient

use one and only one unit of fertilizer

subsidized price. If she saves, she will thus save enough

always follow through on

to

Therefore, there

is

fertilizer until period 2,

purchase one

to

at the

unit,

period

in

1

heavily

and she will

no time inconsistency issue for

and will buy exactly one

her,

unit,

Overall, a heavy subsidy will induce 100 percent fertilizer usage, but will cause the

always-patient farmers and the stochastically impatient farmers

both periods to overuse

3.4

(pfi

Consider the impact of a small discount on

to the

to

be patient

in

fertilizer.

Impact of Time-Limited Discount

corresponds

who happen

case in which pfi

<

1

<

1

and p/2

=

fertilizer, valid in

and pf2

=

1).

1)

period

Consider

a

1

only (which

discount that

is

not large

12

enough

make purchasing two

to

will see that this

To make

purchase

to

m period

1

even

farmer (we

for a patient

assumption since the necessar>' discount will be small).

farmer prefer purchasing

2, the

penod

fertilizer in

period

waiting to

to

1

price needs to be such that:

1

;

x-—^ + piy{\)-f) + {l-p)0H<x-pfi-f + l3Hy{l)'

.

we

a reasonable

a patient period

fertilizer

-

If

is

units of fertilizer profitable,

(11)

define p}i(R) as the price that just satisfies this condition for a farmer with return

investment

i?,

then /yyj(/?)

.—

Note

that

p*^(/?)

when p

is

IS

given by:

^_,

_

,

..

= /(p/3^_l) + /3^(l-p)(y(l)_l) +

close to

the price

1,

p*^j

{R) differs from

the utility cost/ plus the foregone return to investment

additional costs that a farmer

who

patient in period

is

choosing between investing one unit

fertilizer are the utility cost

in the

period

of purchasing the

1

1

1

(p^)- The

-^.

by

.

(12)

a term proportional to

intuition

that the

is

has to immediately bear

only

when

investment and buying one unit of

fertilizer,

and the foregone investment

opportunity. Thus, the fanner just needs to be compensated for incurring the decision and

shopping cost / up

investment. If the returns to the period

reduction

in the utility cost

induce the farmer

to

period

2.

An

to the

(such as free delivery

in

period

1,

1

may

)

then be sufficient to

instead of relying on her period 2

'

the impact of a subsidy

m

period

1

to

an unanticipated subsidy in

unanticipated period 2 subsidy will not affect the period

1

f -

p*j.-,-

induce

3Ly(l).

fertilizer

We

denote the p/n. which just

purchase, the discount

now needs

satisfies this inequality as

to

m which

fertilizer price

of

u(l)

is

close to

1

+

/

incumng

(so that the return to fertilizer

from an ex ante perspective), the discount

1

is

is

the utility cost /:

just positive at a

approximately the cost of

delaying one unit of consumption for one period for an impatient person. Thus,

discount

m

penod

discount

in

period

1

will

In order to

be large enough to compensate an

impatient fanner for postponing consumption of py2, not only for

in the case

An

decision.

if

<

1

investment are low, even a small discount, or a

impatient period 2 farmer with sufficient wealth will decide to use fertilizer

Pf2

period

,

compare

useful to

1

switch to buying fertilizer in period

self to purchase fertilizer.

It is

foregone returns

front, rather than later, as well as for the

have as large of an effect on ultimate

fertilizer

use as

a

small

a large

2.

13

who

In each case, the farmers affected will be those

are patient in period

1,

but impatient

in period 2.

3.5 Choice of

Finally,

us examine what will happen

let

which she

Timing of Discount

gets a small subsidy. Specifically,

induce patient period

farmers

1

induce impatient farmers

to

buy

=

farmer can choose either p/j

Consider

first the

farmers

investment opportunity

request the subsidy

is

in the

fertilizer in period 2.

purchase

fertilizer.

1

-

(5

who

we

1

large

enough

some

to

to

fixed discount 5 and the

price in the other period remains

Because the return

to the period

1.

I

it is

second period.

they will save in anticipation of buying

In period

and will follow through on

who

penod

1,

low, those farmers will always

that plan.

always impatient. They are not planning

are

probabilit)' that they will

the small discount in

is

The

(5.

are always patient.

they are in principle indifferent on

even some small

-

is

to the date at

immediately but not large enough

Suppose there

=

period

consider a subsidy that

fertilizer

or pjo

in

always positive even when

Next, consider farmers

fertilizer, so

to

farmer can commit

if the

2, rather

when

be patient

to get the return.

to

save or use

However,

in the future, they will

if

choose

there

is

to receive

than refuse the program.

Finally, consider the case of the stochastically impatient farmers. If the discount does not

reduce the price of fertilizer below

discount

in

period

immediately

in

2,

p'f-^{R),

because the discount

period

1

so the only

way

patient in both periods. In what follows,

then farmers will always choose to take the

not big enough to induce them to buy

is

buy

that they will

we

fertilizer is if

consider the case in which S

In this case, if a farmer chooses to receive the discount in period

is:

•,

.

,

chooses

If she

to receive the

"

^k[x

•

Note

first that

discount

they happen to be

•

.^

..

,

period

in

1,

>

I

—

p'j^{R).

her expected utility

.

2,

her expected

utility

is:

+ p\y{l)-^^-f]+p{l-p)Pf2Y^]

(14)

current impatience does not affect this decision (since farmers discount

future periods at the

same

rate in period 0).

Second, observe that when

long as p does not equal zero, the farmer will chose the discount

farmer does not care whether the period

gain to delaying the decision

is

1

in

R

close to zero, so

is

period

all

1

:

since the period

or period 2 fanner pays the utility cost, the only

the return to the period

1

investment opportunity'. However,

.14

.

as

R

increases, the value of delaying the discount to period 2 increases, and if j'?

is

high

Thus, depending on

enough, the farmer will choose

to receive the

whether the returns

opportunity are high or low. the farmers will choose

the returns in period

3.6

period

to

I

or in period

1

discount in period

2.

receive

to

2.

Summary

To summarize,

Some

1

the

model gives

rise to the

make

farmers will

following predictions.

plans to use fertilizer but will not subsequently follow

through on their plans.

2.

Farmers will switch

3.

A

fertilizer

2.

in

m

small reduction

and out of fertilizer use.

the cost of using fertilizer offered in period

purchases and usage more than a similar but unexpected reduction offered

The subsidy only needs

to

be large enough

the period

1

investment.

A

the

same discount

Therefore,

buying

period 2.

in

4.

if there are

some farmers

it.

period

for incurring the

well as for the foregone returns to

in

period 2 to induce the same

I.

will

choose the discount

would always prefer

who choose

to

period

1.

Recall that

receive the discount in period

the discount in period

some fanners

in

or

1

I

and follow through by

are time inconsistent,

and have

at least

some

.

.

Testing the Model

As noted above,

of farmers

made

We

farmers

suggests that

fertilizer, this

awareness of

needed

in

farmers are offered an ex-ante choice betVi-een a small discount in period

for a positive R, time-consistent farmers

2.

later, as

larger subsidy will be

increase in usage as a small subsidy in period

When

compensate the farmer

to

decision and shopping cost up front, rather than

4.

will increase

1

who

there

is

some empirical evidence

in favor

of predictions

1

and

2: in a

participated in the demonstration plot program, two-thirds of those

sample

who had

plans to use fertilizer do not end up carrying through with these plans (prediction

also find significant switching

between using and not using

1).

fertilizer (prediction 2): a

regression of usage during the main growing season on usage in the main growing season

previous year (as well as a

full

vector of controls) gives an R" of only 0.25. Suri (2007)

similarly finds considerable switching in and out of fertilizer use in a nationally

representative sample.

15

Of course, we may

not want to attach

much weight

to the declared intentions

and therefore discount the evidence on prediction one. Similarly, other

switching

in

and out of fertilizer

use.

We

Dutch

We

fertilizer use.

stories could generate

therefore focus on predictions 3 and 4 below.

Predictions 3 and 4 of the model suggest that

impacts on

of farmers

some simple

interventions could have large

collaborated with International Child Support (ICS)

NGO that has had a long-lasting presence in

Western Kenya, and

well

is

-

Africa, a

known and

respected by farmers, to design and evaluate a program using a randomized design that

encourage

fertilizer

use

if

predictions of the model,

them with

farmers did indeed behave according

we implemented

to the

model. To

would

test the

multiple versions of the program, and compared

alternative inten.'entions. such as a fertilizer subsidy and reminder visits.

4.1.TheSAFI Program

The main program was

called the Savings and Fertilizer Initiative (SAFI) program.

program was

first

piloted with

with farmers

who

participated in the on-farm trials described in Duflo, et

pilot

programs,

we

minor variations over several seasons on

focused on acceptance of the program and willingness

2003 and 2004, the program was implemented on

determine

Basic

In

its

impact on

its

a

fertilizer

a larger scale,

The

very small scale

al.

to

(2008). In these

buy from ICS. In

and we followed fanners

to

usage.

SAFI

simplest form, the

SAFI program was

any combination of planting or top dressing

offered

at

fertilizer.

harvest, and offered free delivery of

The basic SAFI program worked

as

follows: a field officer visited farmers immediately after han'est, and offered them an

opportunity' to

farmer had

to

buy

a

voucher for

decide during the

fertilizer, at the

visit

regular price, but with free delivery.

whether or not

buy any amount of fertilizer. To ensure

to participate in the

The

program, and could

that short-term liquidity constraints did not

prevent

farmers from making a decision on the spot, farmers were offered the option of paying either

in

cash or

in

by offering

maize (valued

free

market

price).

To avoid

distorting farmers' decision-making

maize marketing services, farmers also had the option of selling maize

without purchasing

who purchased

at the

fertilizer.

fertilizer

was not overvalued

m

Across the various seasons, the majonty (66 percent) of those

through the program bought with cash, which suggests that maize

the program. Participating farmers chose a delivery date and received a

voucher specifying the quantity purchased and the delivery

date.

Choosing

late delivery

16

would provide somewhat stronger commitment

be re-sold

The

(at

some

cost)

and the vouchers themselves were non-transferable.

SAFI program could have reduced

basic

reduced procrastination,

is

use fertilizer since fertilizer can potentially

to

two ways.

in

typically about a 30 minute tnp

First,

it

the utility cost of fertilizer use, and thus

can save a tnp

town

to

to

buy

from the farmers' residences. Suri (2007) argues

distance to a fertilizer provider accounts for her surprising finding that those

had the highest return

typically available in

to

using fertilizer are some of the least likely to use

major market centers around the time

maize crops. Since most farmers

travel to

errands, they could pick up fertilizer

it

is

it.

that

who would have

Fertilizer

and offering

a

market centers occasionally for shopping or other

when

they go to town for other reasons.^

simple option, the program

thinking through which t^'pe of fertilizer to use, and

SAFI with

To

test

to

this visit,

earlier, in a

fertilizer

would

naive, they

purchase

in

use fertilizer would then invest

to

penod

would

lead to

to invest in

low ultimate adoption.

investment opportunit}' has

remms

for transport.

On

a

would take

who makes

time, or about

1

1,

and be

fertilizer in

period

2.

m

the

This

our model, stochastically hyperbolic farmers whose

high return also choose a

the

who have

SAFI program

who bought

fertilizer

of 135 Kenyan shillings), and only

the average fanner roughly an hour to

SI a

and purchase

1

of the investment, but those

average, fanners

fertilizer (at a total cost

It

period

farmers were present-biased but completely

period

In

Most farmers who bought fenihzer through

pay

2. If

in

also have chosen a late delivery date, since they expect to be patient

and would then plan

forgoins the

told that,

standard exponential model, farmers would be expected to

who want

future,

1

SAFI program: farmers were

when

decide

to

they would have the opportunity to pay for fertilizer and to choose a deliver)'

a late visit: those

prepared for

penod

quantit}'.

our model) and offered the opportunity'

in

be visited again later to receive a

As discussed

choose

what

reduced time spent

prediction 4 of the model, in the second season of the experiment, farmers were

they wanted

date.

m

may have

field

ex-ante choice of timing

visited before the harvest (period

during

is

needed for application for

Second, and more speculatively, by requiring an immediate decision dunng the

officer's visit

which

fertilizer,

walk

to

1

a

d)d not

through the

avoid

late deliver)' date to

low return investment

buy enough

that they

would have had

to

SAFI program bought SJ kilograms of

percent of farmers bought more than 10 kilograms.

town, buy

fertilizer,

and walk back. For

day over an eight-hour workday, the SAFI program would save her about SO.

a

farmer

13 in lost

work

percent of the cost of the fertilizer bought by the average farmer. This cost would be

substantially smaller if the farmer

were gomg

to

town anNavay and so would not miss any work time.

17

opportunity in period

eventually use

4.2

1

will

chose an early delivery date,

to increase the probability that

they

fertilizer.

Experimental Design

Two

SAFI programs were implemented

versions of the

experiment, allowing for a

test

as part

of a randomized

field

of the model. Farmers were randomly selected from

frame consisting of parents of fifth and

sixth grade children in sixteen schools in

Busia distnct. The program was offered to individuals, but data was collected on

fanned by the households. And

a farmer

was considered

The experiment took place over two

seasons. In the

on any plot

in the

to

use fertilizer

sample of farmers was randomly selected

randomization took place

to set

at

plots

all

was used

season (beginning after the 2003

first

in the

2004 long

form of "starter

kits'"

(a

to test the

2004

program

to

by school,

class,

provide farmers with small

they could use on their

short rains), the

rains season), a

SAFI program. The

receive the basic

own

-

up demonstration plots on the school property).

enriched design

Kenya's

if fertilizer

the individual farmer level after stratification

In the following season (the

some

to

two prior agricultural programs

in

amounts of fertilizer

program

sample

household.

short rain harvest, in order to facilitate fertilizer purchase for the

and participation

a

farm, and a

.

;

;

,/,.•

program was repeated, but with an

main empirical predictions of

the

model

in

Section 3 as well as

predictions of alternative models. All treatment groups were randomized

at the

individual level after stratification for school, class, previous program participation, and 2003

treatment status.

First, a

new

set

of farmers was randomly selected to receive a basic SAFI

another group of farmer was offered

SAFI with

visit.

Second,

ex ante choice of timing (as described above).

Third, to test the h^'pothesis that small reductions in the utility cost of fertilizer have a

bigger effect

fertilizer

if

needs

offered in period

to

1.

another group of farmers was visited close to the time

be applied for top dressing (approximately 2 to 4 months after the previous

season's harx'est, the equivalent of period 2

fertilizer

was

with free delivery.

visited during the

To

in

our model), and offered the option to buy

calibrate the effect of a discount, a fourth

same period, and offered

us to compare the effect of a 50 percent subsidy

the

SAFI program.

fertilizer at a

to the effect

In all of these programs, farmers could

planting, top dressing, or both.

However, one caveat

to

group of farmers

50 percent discount. This allows

of the small discount offered by

choose

to

bear in mind

buy

is

either fertilizer for

that in the late visits

18

many

farmers had already planted and could only use top dressing

farmers preferred using

fertilizer for

.

fertilizer at planting,

however, they could have bought planting

use in the next season, so a standard model would suggest that these farmers

should have taken advantage of the discount for

later use.

subset of farmers was offered the option to

the field officer before the

to test the alternative

way

cash

m

program took

hypothesis that the

to protect their

who

thus arguably easier to waste. If the

is

-

•

comparison group,

a

random

quantity of maize at a favorable price to

The objective of this

additional treatment

SAFI program was just seen by

accepted the offer, which

SAFI

to take

is

more

up.

to

was

the farmers as a

some

liquid than maize,

main reason why farmers purchased

because of an aversion

have encouraged them

place.

,

.

,

savings than available alternatives. The purchase of maize put

the hands of the farmers

SAFI program

sell a set

,

.

Finally, in each of the intervention groups as well as in the

safer

If

fertilizer in that season.

fertilizer

and

under the

holding liquidity, the purchase of maize should

Under our model,

this

would make no

difference,

however.

Appendix

4.3

figure

1

summarizes

the experimental design for this second season.

Data and Pre-Intervention Summary

The main outcome of interest

an intermediate outcome.

We

is

Statistics

fertilizer use,

with

fertilizer

have administrative data from ICS on

the program. Data on fertilizer use

was

collected

at

harvest) for that season and for the previous season.

fertilizer

in

in

fertilizer

purchase under

baseline (before the 2003 short rains

We

usage data for the three seasons following the

2004 and one season

purchase through the program as

later visited

first

farmers

SAFI program

to collect

(i.e.,

both seasons

2005). The baseline data also included demographic information

and some wealth characteristics of the sampled households.

In

members farm

polygamous households), we

asked each

different plots (which

member

is

individually about fertilizer use on her

own

plot,

use on each

plot.

The data

of the household (the husband) about

household

Table

fertilizer

and

we

is

asked the head

aggregated

at

the

level.

1

shows descriptive

participate in the basic

statistics. In

eligible for the

season one, 21

SAFI program, and 713 farmers

season two, 228 fanners were eligible

retail price

tvpically the case in

households where different

1

farmers were eligible

constituted a comparison group. In

to participate in the basic S.A.FI

SAFI with ex ante choice of timing; 160 were

with free deliver)'

at

to

program; 235 were

offered fertilizer

at

the normal

top-dressing time; and 160 were offered fertilizer

at

half

19

price with free delivery at top dressing time.

An

additional 141 farmers served as a

comparison group.

There were some relatively minor pre-treatment differences between groups

However, there were some pre-treatment differences

fertilizer.

each

SAFI and comparison groups had previously ever

season. In season one 43 percent of both

used

in

comparison group farmers had 0.6 more years of education

percent level), and were about 5 percent less likely to live

in other observables:

(a difference significant at the

home

in a

mud

with

mud

floors,

mud

walls, or a thatch roof (though only the difference in the probability of having a

10

floor is

statistically significant, at 10 percent).'

In season two, the

program

(table

1

,

comparison group was more

likely to

have used

fertilizer prior to the

panel B). The point estimate for previous fertilizer usage

is

5

1

percent for

the comparison group, but only betvv'een 38 percent and 44 percent for the various treatment

groups.

Many

of these differences are significant

10 percent level (the difference

at the

comparison group

significant at 5 percent for the 50 percent subsidy group). In addition, the

has significantly

(at

10 percent)

more years of education than

the

is

group offered SAFI with

the ex ante timing choice.

These pre-treatment differences are

bias our estimated effects

downwards.

in general relatively

We

minor and would,

anything,

if

present results with and without controls for

variables with significant differences prior to treatment

—

inclusion of these

in all cases, the

controls does not substantially affect our results.

5.

Results

..:'.,:',

'•,-

.;r„.

'"''''

>....;„,

,,•;,;

-^^

''.-.'

'

'

.

;,,

'

'

'

5.1

The SAFI Program

The SAFI program was popular with

were offered SAFI bought

fertilizer

offered the basic version of

those offered

fertilizer is

Appendix

appearance

sampled

SAFI with

table

at

percent of the farmers

who

to the

through the program, as did 41 percent of

fertilizer

The

fraction of farmers

who purchase

impact of the program on use: some program farmers

suggests that attrition patterns were similar across groups. Regressions of indicators for

1

pre-treatment background and post-treatment fertilizer adoption questionnaires on being

for treatment yield

do not appear

1

through the program. In season two. 39 percent of those

SAFI bought

of course not equal

in the

fanners. In season one. 3

ex ante choice of timing.

no significant differences between groups. Overall,

and we obtained adoption data

not

\^,

^^.

i^'

in the dataset

for

925 of them (75.1 percent). There were few

were not known by other parents

home when ICS enumerators

visited their

in the

1

,232 farmers were sampled,

refusals.

Nearly

all

of those

who

school and so could not be traced, or were

homes.

20

1

who were going

to

use

fertilizer

anyu'ay presumably bought

may

advantage of the free delivery. In addition, some fanners

purchased through SAFI on

their

fertilizer

through SAFI,

take

to

not have used fertilizer

maize crop: they could have kept

sold

it.

used

it,

it

some

on

other crop, or the fertilizer could have been spoiled. In the 2005 adoption questionnaire 76.6

percent of the farmers

who purchased

on the plot of

plot, 7.3 percent

under SAFI reported using

wife or husband, and

their

8.1

it

on

their

own

percent reported saving the

use in another season. The remainder reported that they had used the fertilizer on

fertilizer for

a different crop

( 1

percent) or that the fertilizer had been spoiled.

.6

Overall, in both seasons, the

on

fertilizer

fertilizer use. In

SAFI program had

compared

percentage point difference

is

34 percent of those

to

significant at the

m the

fairly sizeable

SAFI program

season one 45 percent of farmers offered the

fertilizer in that season,

and

a significant

report using

comparison group. ^ The

percent level (see table

1

impact

1

panel A). In

1,

season two (the 2004 short rains), the basic SAFI program increased adoption by 10.5 percent

(table

panel B).

1,

.

Table 2 confirms these results

in a

regression framework. For season one,

we

run

regressions of the following form:

y,

where

a

y, is a

dummy

dummy

= Q+

/3:T,^«

+ A77 +

/'

was offered

the

'/

is

SAFI program

of control variables for the primary respondent

a vector

-

indicating whether the household of farmer

indicating whether farmer

(15)

•

£-

in the

using

in

fertilizer,

Ti^^

season one, and

is

A", is

household, including the