IE Ipiiili iiiliiiiiii iiiS

advertisement

'a

MIT LIBRARIES

m

3 9080 02237 2673

i

11

iliiiilililillli:

m

!i

^1

iiii

Mliit;

iiiS

:;i|||i

il'I'ii'.fiiiHI'iri.i:.!!/'!'

lffl^^l!f!/Wli;);Mllffl;l'i::

:;:||li|li|||j||ii|f||||||||p^^^

-'iifeiisfv.,

,

llliiiill

iiii:

iiiiiii:

-iiiiii Ipiiili

iiiliiiiiii

\Mi!i(i;i!i;iiSll

:i,;!!iiii|i!l;:|!;!|

IE

LIBRARIES

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/doceossettheirowOObert

^^H^y

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

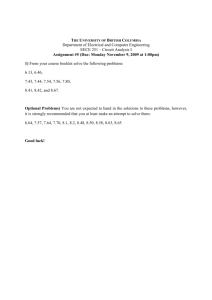

Working Paper Series

DO CEOs SET THEIR OWN PAY?

THE ONES WITHOUT PRINCIPALS DO

NBER

& NBER

Marianne Bertrand, UChicago &

Sendhil Mullainathan, MIT

Working Paper 00-26

September 2000

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

This paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research

Network Paper Collection at

http:/ /papers. ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstractJd=223736

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

OCT

3

2000

LIBRARIES

ABSTRACT

We empirically examine two

competing views of CEO pay. In the contracting view, pay is used

to solve an agency problem: the compensation committee optimally chooses pay contracts that

give the CEO incentives to maximize shareholder wealth. In the skimming view, pay is the

result of an agency problem: CEOs have managed to capture the pay process so that they set

their

own pay,

constrained somewhat by the availability of cash or by fear of drawing

shareholders' attention.

To

luck, observable shocks to

luck, such as

changes

responds about as

better

distinguish these views, we first examine how CEO pay responds to

performance beyond the CEO's control. Using several measures of

in oil price for the oil industry,

much

governed firms pay

their

CEOs

less for luck.

are charged for the options they are granted.

might offer an appealing way

in better-governed firms are

that

we

find substantial

to a "lucky" dollar as to a general dollar.

to

Our second

test

pay

for luck.

importantly,

Since options never appear on balance sheets, they

skim. Here again

we

find a crucial role for governance:

and

little

fits

better (pay

charge for options) while in well-governed firms, the contracting view

better (filtering out

of luck and charging for options).

JELNo. G3,J3,J4, L2

CEOs

charged more for the options they are given. These results suggest

both views of CEO pay matter. In poorly governed firms, the skimming view

for luck

Pay

we find that

examines how much CEOs

Most

fits

Introduction

1

There are two predominant ways to think about

CEO

pay.

contracting view, relies on principal-agent models. Because

The

CEOs

they control, shareholders face a classic moral hazard problem:

firm value in making their decisions.

one, which

often

we

own very

CEOs may

CEO

refer to as the

little

of the firm

not always maximize

Under the contracting view, shareholders

the board or the compensation committee) use

for

first

(acting through

pay to reduce moraJ hazard.

Explicit

pay

performance, such as long term contracts or options, and implicit pay for performance, such

as a bonus payment, are all used

by boards to increase CEOs' incentives

to

maximize shareholder

wealth.^

The second

view, which

such as Crystal (1991).

pay.

refer to as the

It also

that this separation allows

board with their

we

begins with the separation of ownership and control, but

CEOs

friends, or

skimming view, has been championed by practitioners

to gain control of the

pay setting process

any other mean of entrenchment, many

They skim what they can from

possible.

Whereas pay

skimming view

We

target.

is

packing the

amoimt

own

of funds in

groups or by a fear of

Within these constraints, however, they pay themselves as much as

in the contracting view is

an attempt

to solve moral hcizard, pay in the

the result of moraJ hazard.

propose two

'Murphy

jictivist

By

argues

de facto set their

shareholders, constrained perhaps by the

the firm, by an unwDlingness to draw the attention of shareholder

becoming a takeover

CEOs

itself.

it

tests to differentiate these

(1985, 1986)

b a

models. In the

first test,

we examine whether CEOs

forerunner of the vast literature that has empirically analyzed

CEO

compensation

summarized in Murphy (1999). The major

econometric work has been to test for vaJue-optimizing incentive scheme by studying the correlation between pay

and performance. Jensen and Murphy (1990) use this framework to argue that political considerations constrain pay

so that incentives are too low. Joskow, Rose £ind Shepard (1993) empirically examine this argument in regulated

industries. Other tests of the agency framework can be found in Gibbons and Murphy (1990), who test for relative

performance evaluation and career concerns, Garen (1994) and Aggarwal and Samwick (1999a), who test for riskreturn treideofe, and Hubbard and Palia (1994) and Bertrand and Mullainathan (1998), who test whether pay

Incentives substitute for other disciplining devices (competition and takeovers respectively).

in the context of the princip>al-agent

model. The resulting literature

is

are rewarded for observable luck.

CEOs'

CEO

By

luck,

we mean changes

in jBrm

performance that are beyond

In simple agency models, pay should not respond to luck since by definition the

control.

cannot influence luck. Tying pay to luck

risk to the contract (Holrostrom, 1979).^

respond to luck since the

CEO

not provide better incentives;

will

Under the skimming view, on

it

will only

add

the other hand, pay will

can divert those "lucky" dollars to pay herself as easily as she can

divert earned dollcu^.

To empirically examine the responsiveness of pay

luck. First,

we perform a

to affect firm

to luck,

we use

case study of the oil industry where large

performance on a regular

basis.

three different measures of

movements

in oil prices

Second, we use changes in industry-specific exchange

rate for firms in the traded goods sector. Third,

we use

year-to-year differences in

performance to proxy for the overall economic fortune of a sector. This

last

mean

CEO

pay

is

CEO

as sensitive to

pay responds

a "lucky

to luck. In fact,

dolleir" as to

we

a "general

indiistry

measure very much

For

resembles the approach followed in the relative performance evaluation literature.

measures, we find that

tend

all

three

find that for all three luck measures

dollar."

This basic finding of pay for luck, however, can be explained by complicating the basic agency

model. For example, suppose boards wanted their

Tying pay to luck in

rewarding the

CEO

open before the

this case

may be

with industry fortunes.

to forecast or respond to luck shocks.

necessary to provide better incentives. In the

after the fact for seeing

fact. Alternatively,

CEOs

an

oil

shock coming encourages him to keep his eyes

suppose the "value" of a CEO's hiiman capital

One would then

oil industry,

find that

rises cuid falls

pay correlates with luck because the CEO's

outside wage moves with luck.

While we wiU argue that these arguments may be incorrect, they motivate us

to search for further

^Note our emphasis on observable luck. In any model, given the r£indomness of the world, CEOs (and almost

everybody else) will end up being rewarded for unobservable luck. Note also our emphasis on the fact that this

prediction holds in simple agency models. As we will discuss shortly, complications to the agency model can in

principle alter this result.

tests.

be

We

therefore

examine another direct implication of the skimming model, that skimming

important in well governed firms.

less

So

control of the pay process.

if

pay

Good

for luck

governance will make

hard for the

it

comes from skimming, we expect

CEO

will

to gain

to see less of

it

in

the better governed firms.

We test

this hypothesis using several

CEO

the board and overall),

proxy

for

measures of governance: presence of large shareholders {on

tenure (interacted with the presence of large shareholders to better

entrenchment), board size and fraction of directors that are insiders.

skimming, we generally find that the better governed firms pay

strongest for the presence of large shcireholders

23 and 33%. Large shareholders are especially important as

CEOs

the idea that unchecked

CEO

These

less for luck.^

on the board who reduce pay

Consistent with

for luck

effects are

by between

tenure increases, consistent with

can entrench themselves over time. The findings on governance cast

doubts on the alternative interpretations which make pay for luck optimal through complications

to the agency model. If

firms use less of

to

be rewairded

at least

it.

pay

were in fact optimal, we would not expect to see well governed

For example, whether or not a large shareholder

for a rise in the vcilue of their

some of the pay

Our second

for luck

around another aspect of

tion in recent yejirs: the greinting of

new

present,

CEOs would

have

humjin capital. These findings instead suggest that

for luck in poorly governed firms is

test revolves

is

CEO

due to skimming by CEOs.

compensation that has received atten-

stock options. Principal-agent theory predicts that

when

options are granted, other components of compensation should be adjusted downwards to leave the

CEO

indifferent. In other words, the

CEO

should be charged for the options she

is

granted,

if

not

their Black-Scholes value then at least this value times a risk correction factor.'* Supporters of the

^Whenever we

for performance.

refer to "less pay for luck" we mean that there is less pay for luck relative to the amount of pay

Thus, these results would not be driven by well governed firms simply giving less overedl pay for

performance.

^The basic idea

is

that options have value. For example, suppose a

price of 50, a horizon of 3 years

because even

if

and the firm

is

CEO

is

granted 10,000 options with a strike

and of themselves

currently trading at 50. These options have value in

the firm under-perfonns relative to the market and earns a cumulative 3-year{nomincil) return of only

skimming view, on the other hand, emphasize that stock options do not appear on balance

sheets.

Because of accounting treatments, firms do not take a financial charge for granting options.

CEOs

can therefore pay themselves through option grants without affecting the company's bottom

Under the assumption that shareholders only

line, the

(or mostly)

line.

pay attention to the accounting bottom

granting of new stock options would represent an easy way to skim more without attracting

No

shareholders' attention.

cut in the other components of pay would be necessary.

Thus while

agency theory predicts a large charge for options, skimming predicts about no charge.

Unfortxmately, a direct measure of

how much CEOs

not possible because of a natural omitted variable bias.

we

findings,

are in fact charged for their options

Taking

on the question of how governance

therefore focus

oiu: lead

from the pay

less for their

new options

grants.

for luck

affects the charge for options.

CEOs

the same measures of governance, we generally find that more poorly governed

For example, for an options grant worth

is

Using

are charged

million dollars (in

1

Black- Scholes terms), an extra large shareholder on the bocird increases the charge for options by

between 30 and 50 thousand

dollars.

As

before,

we

also find that as

a

CEO

tenure increases, the

charge for options diminishes in firms without a large shareholder.

In summary, this paper contains three

main

results. First,

CEO compensation shows on average

a significant amount of pay for luck. Second, well governed firms display

that

it is

possible to filter out luck. Third,

stock options grants.

view.

CEOs

At a

first

CEOs in

seem

10%, he

still

will arise

gains

(.1)

50

the firm's natural

each option.

volatility.

more

for their

skimming

and seem to be able to skim using options. But notice that they

and do manage to charge more

for options.

do manage

We

feel

to filter out

some

that the results suggest

000 = 50, 000 dollars. Even if the option is granted out of the money, the same effect

may come into the money just because of movements in share price that comes from

Agency theory therefore predicts that CEOs should be charged for the gift implicit in

10,

because the option

for luck, suggesting

to provide support for the

also provide support for the contracting view. Well governed firms

luck from performance

pay

well governed firms are charged

glance, these results

are rewarded for luck

less

as a whole that both views of

CEO

is

an

is

more of an

Worse governance means that there

his

own

pay.^

The

rest of this

performance

paper

is

be

pay contracts. Better

active "principal" (or principals) present to actually design

governance means that there

to

skimming or the contracting model depending on the extent to

better characterized by either the

which there

pay are true. In practice, executive compensation seems

is less

active principal and optimal contracting

organized as follows.

We

filtering (section 2).

CEO is

of an active principal and the

first

We

start

by presenting our

more

fits

better.

likely to set

test of the lack of

present a very simple theoretical background (section

2.1),

review the existing evidence (section 2.2) and explain the empirical methodology (section

2.3).

We

then establish the existence of pay-for-luck, both in the specific case of the

(section 3.1)

and

for

more general

sets of industries (section 3.2). In section 3.3,

the role of governance in limiting the extent of pay-for-luck.

same governance

variables also matter in limiting the gift nature of

siunmarize and conclude in Section

Pay

2

Luck

Test:

new

we

4,

industry

we demonstrate

establish that the

stock option grants.

We

5.

Background

Theoretical Background

2.1

Our

for

In section

oil

first test

model

will

focuses

make

on whether

precise

CEOs

are rewarded for observable luck.

what agency theory says about the reward

for luck.

A

simple theoretical

Consider a standard

agency setup where risk-neutral shareholders, perhaps operating through the board, try to induce

a risk-averse top manager to maximize firm performance.

Since the actions of the

CEO

can be

'This confirma the sentiment that emerges from conversations with compensation consultants as they describe

being hired by two types of firms: the ones where they clearly have to respond to the

clearly

have to respond to the shaureholders.

CEO

and the ones where they

hard to observe, shareholders

will

be unable to sign a contract that specifies these actions. Instead,

shareholders will offer a contrax:t to the

CEO

where her compensation

level is

made

depend

to

on the firm's performance. Let p represent firm performance and a the CEO's actions, which by

assumption are unobservable by the shareholders. Firm performance depends on the actions of the

CEO

and on random

factors.

We

split

the

random

feictors into

observed by shareholders and those that cannot. For an

an observable random

term,

factor.

Under some technical conditions, Holmstrom

two

p and

o,

oil

CEOs

s

for

u be the unobservable

cuid

Milgrom (1987) calculate the optimal incentive

Since shareholders can only observe

= Q + /3(p - Jo) = a + ;0(a + u)

filters

(1)

the observable luck firom performance. This

because leaving o in the incentive scheme provides no added benefit to the principal

definition, the agent has

no control over

Beyond providing no

effects.

o.

"Incentivizing" her

How

more

benefit, it actually costs the principal

we need

filtering of luck to

to assume that the

general result can be found in

^In Section 3.2.4,

by

because not

filtering

out luck

mean pay

risk averse agent.

might we expect

'Essentially,

A much

as,

on o has therefore no incentive

increases the variance of the incentive scheme, thereby forcing the principal to increase

compensate the

noise

performance net of the observable factor.

In other words, the optimal incentive scheme

to

would be

the incentive scheme could at most depend on these two variables. In fact,

shareholders wiU only reward

is

crude

as:

for this model.^ Let s denote this incentive scheme.

variables,

firm, the price of

Letting o be the observable factor and

we assiune that performance can be written

scheme

oil

two components: those that can be

we

will consider

CEO

occur in practice? Explicit incentive contracts, such as

has

CARA

Holmstrom

utility

and that outcomes

follow

(1979).

changes to this basic model that might alter these

results.

a Brownian process.

options, rarely

filter.

For example, options axe rarely

if

ever indexed against market performance.

This need not be inconsistent with a lack of filtering, however. One might expect that the best way

to filter luck

through the use of subjective performance evaluation. In practice, we would expect

is

the board to be the primary mechanism for doing this.

components of

pay, such as bonus, salary or

new options

The board should

use the discretionary

grants, to respond to luck shocks.

Existing Evidence

2.2

Previous work already hints at a relationship between pay and luck.

and

de-Silanes

Shleifer (1992) find that windfall gains

from court rulings

Second, as we just mentioned, the stock options that are granted to

While

to the market.

interesting, these

luck, but rather the result of the

CEOs

two facts are only suggestive.

CEO's work. And,

First,

A

Blanchard, Lopez-

pay

raise the

of

CEOs.

are very rarely indexed

court ruling

as noted, while options

may

may

not be

not be indexed

(perhaps for simplicity or tax reasons), the board can always reissue them or adjust other parts of

pay.

For many, the apparent lack of relative performance evaluation (RPE)

existing piece of evidence of

First,

may

mean

pay

for luck.*

Even with

this evidence though,

industry movements aie a special form of luck.

fact.

themselves note that relative performance evaluation can distort

actions that affect the average output of the reference group."^

a

specific

model

in

probably the best

some problems

arise.

Filtering this specific kind of luck

not be optimal from an agency theoretic point of view. In

also develop

is

Gibbons and Murphy (1990)

CEO

incentives

if

they can "take

Aggarwal and Samwick (1999b)

which relative performance evaluation schemes may not be optimcil

*While Gibbons and Murphy (1990) find some evidence for RPE, some of their results are puzzling. For example,

there appears to be more filtering of general stock market shocks than of shocks specific to the relevant industry.

Most

of the other

evidence of

®They

work on the

topic, such as

Janakiraman

et al. (1992)

and Aggarwal and Sajnwick

(1999a), find

no

RPE.

list

externalities.

four different kinds of such actions:

sabotcige, collusion, choice of reference

group and production

for shareholders aa they try to provide

We

criticisms.

movements.

will

CEOs

with the best incentives. ^"^ Our test addresses these

examine a variety of shocks, including but not

We will verify that other shocks to performance that are

managerial influence, such as shocks to the price of crude

be

oil

restricted to

mean

industry

even more objectively beyond

or exchange rates shocks, also

fail to

filtered.

Empirical Methodology

2.3

Within the agency framework, moat of the empirical

Vit

where

denotes total

yit

fixed effects,

Xn

CEO

=

oii

+ at + ax

*

^it

compensation in firm

are firm (and

resents a performance measure.

CEO)

The

i

literature estimates

+ P * per fit +

at time

t, a,-

an equation

eu

(2)

are firm fixed

efi'ects,

specific variables such as tenure or firm size,

coefficient

^

of the form:

at are time

and per fit rep-

captures the strength of the pay for performance

relationship.

Performance

and we

will xise

literature

is

typically

measured either as changes

both measures.^*

and our paper

is

in accounting profits or stock

In measuring compensation,

no exception.

Ideally, the

y^t,

market returns

one problem permeates the

compensation in a year would include the

change in value of unexercised options granted in previous years. Such a calculation requires data

on the accumulated stock of options held by the

information on

include this

new options granted each

component of the change

CEO each year,

whereas existing data contains only

year. Consequently, our

As we

in wealth.

compensation measure does not

discuss in Section 3.2.1, this data problem

'''The basic idea is that the niean performance in the rest of the industry may actually provide some information

about the CEO's effort to attenuate or strengthen the level of competition in that industry. For example, if product

market competition in an industry needs to be softened, shcireholders might in an efficient contracting environment

reward the CEO when the rest of the industry is doing well as this might indicate that the CEO acted successfully

in

attenuating the competitive pressures in that industry.

"These

profits as

are flow measures. In practice, given the firm fixed effects,

measures of perfn.

10

we

will

use market value and level of accounting

should,

if

anything, bias our results towards overstating the case towards filtering and understating

the extent of pay for luck.

To estimate the general

sensitivity of

pay to performance, we

will

foUow the

estimate equation (2) using a standard Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model.

pay to

sensitivity of

stage,

we

luck,

will predict

we need

more complicated two stage

to use a

two stage procedure

where the luck variable

is

Letting o be luck, the

procedirre.

estimate the

In the

first

is

how

sensitive

pay

is

to these predictable changes

essentially aJi Instrumental Variables (IV) estimation

the instrument for performance.^^

first

equation we estimate

is:

~ ai+at + ax * X^ + b * oa +

perfit

where ou represents the luck measure

(oil

price for example).

predict a firm's performance using only information about luck.

this luck

To

and

performance using luck. This will isolate changes in performance that are

caused by luck. In the second stage, we will see

in performance. This

literatiure

en

(4)

Again, this equation allows us to

We

then ask how pay responds to

induced performance, perf^^:

yu

The estimated

=

ai

+ at + ax * Xu + PlucK

coefficient pLj^ck indicates

firom luck. Since

such changes should be

how

pay

sensitive

filtered, basic

*

per fit

is

+ en

to changes in

(5)

performance that come

agency theory predicts

/3[,y,ck

should equal

0.

'^One might wonder why we should use this procedure rather than simply include o directly into the pay

performance equation (2) and run OLS to estimate:

Vit

=

at

+ at + ax

*

Xit

+

*

perfu

+7

o

+ e<e

for

(3)

hard to interpret, however. Even if there is no pay for luck, the coefficient 7 will not equal —p but

see from equation I. Since we we do not estimate S, the estimated coefficient 7 can be small

either because there is pay for luck or simply because S is small. The first equation in the IV procedure, on the other

hand, scales the effect of luck on performance, circumventing this problem.

This equation

rather —05, as

is

we can

11

Testing for Pay for Luck

3

Study

Oil Industry

3.1

We now tiim to

the

the price of crude

oil

oil

industry to test whether in fact there

profits.

would have found that a measurable variable

Over

US CEO.

this period,

(oil prices)

Moreover, these large fluctuations in crude

control of a single

oil

its

OPEC.

price increase between 1979

Oil price

As Figure

1

shows,

and 1981

is

of one of these firms

greatly influenced the performance of

prices are likely to have

oil

been beyond the

CEOs

US

of

end of 1985

price at the

petroleum policy and to increase

an action hardly attributable (and never attributed) to the

oil

CEO

a

For example, the sharp decline in crude

was caused by Saudi Arabia's decision to reform

large

zero pay for luck.

has fluctuated dramatically over the last 25 years. These large fluctuations

have caused large movements in industry

his firm.

is

oil firms.

it

production,

Similarly, the

usually attributed to an internal policy change by

movements therefore provide an

ideal place to test for

pay

for luck:

they affect

performance, are measurable and axe plausibly beyond the control of the CEOs.

We use a data set on the pay and

performance for the 51 largest

and 1994 to implement the methodology of the previous

analysis,

it is

In Figure 2,

industry.

useful to look directly at

we have graphed changes

Two

how pay

section. ^^

same

pay changes

sign:

both

au^e

oil

companies between 1977

Before moving to regression

compared to the movements in Figm-e

in oil prices for each year

striking facts emerge. First,

In 12 of the 17 years, they are of the

fluctuates

US

1.

and changes in mean log pay in the

cind oil price

up or both

changes correlate quite weU.

are

down. This

is

suggestive of

a large amount of pay for luck. The second fact comes firom the remaining 5 years where they are

'^We are extremely grateful to Michael Haid for making the data set used in this Bection available to us. See

Haid (1997) for further details about the construction of the data set. Tiible Al in the appendix provides mean

and standard deviations for the main variables of interest. While the original data set covers 51 companies over the

period 1977 to 1994, information on CEO pay is available for only 50 of these original 51 companies. Moreover, CEO

pay is available from 1977 on for only 34 of these 50 companies. The final data set we use covers 827 company /year

observations.

12

of opposite sign:

all

these 5 years

CEOs

an asymmetry: while

for

bad

luck.

This

to the

While we

figure,

pay

will

cire

years in which

oil

are always rewarded for

price drops but pay does not. This hints at

good

luck, they

not formally pursue the asymmetry,

it is

may

not always be punished

worth keeping in mind.

how

however, does not allow us to quantify the size of pay for luck:

for general

performance?

might be changing over time. Table

It also

1

does

it

compare

does not control for other firm specific variables that

follows the empirical

methodology presented

in Section 2.3,

which allows a more systematic analysis. The regressions use log(total compensation) as dependent

variable

and include firm

dependent

variables.*'*

fixed effects, age

We

also allow for a year quadratic to allow for the fact that

has been trending up during this period.

change

in

and tenure quadratics and a performance measure as

accounting performance.

The

Column

(1) estimates

in pay.

coefficient of .82 suggests that

if

an

oil

Note that the sign and magnitude of all the other covariates

firm increases

* .01

one percentage point increase in accounting returns leads to a

Pay increases with age and

.8

=

.0082

«

1

its

log

percent increase

in the regression

seem

Both the age and tenure

to a lesser extent with teniu-e.

pay

the sensitivity of pay to a general

accounting return by one percentage point, total compensation rises by .82

points. Roughly, a

CEO

sensible.

profile are

concave (the negative coefficient on the quadratic term).

Colimin

with log

due to

(2) estimates the sensitivity of pay to luck.

oil prices.'^

oil price

As

described,

we instrument

for

performance

This aUows us to narrow down on movements in accounting returns that are

changes.

The

coefficient in

column

percentage point rise in accoimting returns due

standcird errors, one cannot reject that the

coefficient are the Scune.

One can however

'"Tbtal compensation in this table

and

all

pay

(2)

now

rises to 2.15.

to luck raises

This suggest that a one

pay by 2.15 percent. Given the large

for luck coefficient

and pay

for general

strictly reject the hypothesis of

complete

performance

filtering:

oil

others includes salary, bonus, other incentive payments and value of

options granted in that year.

"This table does not report the first stage regressions of performance measure on

expect from Figure 1, these regressions show very significant coefiicients on oil price (p

13

oil price.

<

.001).

But as one would

CEOs

comes from

are paid for luck that

Columna

(3)

and

(4)

The

shareholder wealth.

oil

price movements.

perform the Scune exercise but for a market measure of performance:

coeflBcient of .38

on column

(3) suggests that

shareholder wealth leads to roughly a .38 percent increase in

CEO

a one percent increase in

pay. In

column

(4),

we

a one percent increase in shareholder wealth due to luck leads to .35 percent increase in

Again, pay

for luck

matches pay

More General

3.2

The

oil

for general

CEO

pay

performance.

much

to

a lucky dollar than

how

foreign competition, exchange rate

Movements

influence

in

how

CEO

mean

It is

only one industry,

We

we

focus on two measures of luck:

By

affecting the extent of

movements can strongly

affect

will

examine

movements

in

import penetration

a firm's profitabihty.

industry performance also proxy for luck to the extent that a

CEO

does not

the rest of her industry performs.^^

Compensation Data

To implement these

1991 period.

is

generalizable these results are. In this section,

exchange rates and mean industry performance.

and hence

performance dollar. This

to a general

luck shocks that affect a broader set of firms.

Shlerfer.

pay.

Tests

however, and one might ask

3.2.1

CEO

industry case study has been instructive about the magnitude of pay for luck.

responds as

find that

we use compensation data on 792

tests,

The data

set

was graciously made available to us by David Yermack and Andrei

extensively described in

the corporations'

SEC

Yermack

Proxy, 10-K, cmd 8-K

(1995).

filings.

Compensation data was

As we mention

before, this \ast assumption

like

is

more

SEC

questionable.

the exx^hange rate movements (and like

14

collected

from

Other data was transcribed from the Forbes

magazine annual survey of CEO compensation as well as from

movements operate exactly

large corporations over the 1984-

oil

Registration statements, firms'

In practice,

we

find that

price movements).

mean

industry

direct correspondence with firms, press reports of

Annual Reports,

stock prices pubhshed by Standard

&

CEO

hires

and departures, and

Firms were selected into the sample on the basis

Poor's.

of their Forbes rankings. Forbes magazine publishes annual rcinkings of the top 500 firma

on four

dimensions: sales, profits, assets and market value. To qualify for the sample a corporation must

appear in one of these Forbes 500 rankings at

least four times

between 1984 and 1991. In addition,

the corporation must have been publicly traded for four consecutive years between 1984 and 1991.

Yermack data

is

attractive in that

it

provides both governance variables and information

options granted, not just information on options exercised.

in the value of options held.

Our compensation measure,

It

on

does not, however, include changes

therefore,

wiU not include the change in

value of pre-existing options. If anything, this biases us towards finding less pay for luck than there

Since options are not indexed, changes in the value of options held wUl covary perfectly with

is.

luck. Including

them would only increase the measured pay

for luck. This data limitation therefore

pushes us towards favoring the filtering hypothesis, making our statistical rejection of complete

filtering that

much

stronger.

Tkble 2 presents summary

statistics for the

main

All nominal variables are expressed in 1991 dollars.

in salary

and bonus. His

thousand

dollars.

The average

compensation

is

CEO

earns 900 thousand dollars

amount

CEO's pay

CEO

data.^'^

at one million

and 600

that are due to options

As

governance goes, the average firm in our sample has 1.12 large shareholders, of which

less

them are

'''in

CEO

nearly twice that

difference indicates the large fraction of a

is

roughly 57 years old and has been

than a fourth are sitting on the board. There

of

The average

Yermack

yccirs.

grants.

far as

The

total

variables of interest in the full

cire

of the firm for 9

on average 13 directors on a board. 42 percent

insiders.^®

practice,

depending on the required regressors, the various

various subsamples of the original data.

None

of these

main

tests in the following sections will

be performed on

variables of interest significantly differ in any of these

subsamples.

'^Ttechnically,

we

define "insiders" to

be both inside and grey

15

directors.

An

inside director

is

defined as a director

Exchange Rate Movements as Measures of Luck

3.2.2

Our

first

general measure of luck focuses on exchange rate movements.

exchange rates between the

US

dollar

may be more

same

yeax.

affected

may be more affected by

by Bolivia, these two industries

by

different countries'

exchange

rates.

We

For

Japanese imports while the lumber industry

may

experience very different shocks in the

This allows us to construct industry-specific exchange rate movements which we are

arguably beyond

The exchange

for

exploit the fact that

and other country currencies fluctuate greatly over time.

also exploit the fact that different industries are affected

example, since the toy industry

We

CEOs'

control since they are primarily determined by

rate shock measure

is

macroeconomic

variables.

based on the weighted average of the log real exchange rates

importing countries by industry. The weights are the share of each foreign country's import in

total industry

imports in a base year (1981-1982). Real exchange rates are nominal exchange rates

(expressed in foreign currency per dollar) multiplied by U.S.

CPI and divided by

the foreign country

CPI. Nominal exchange rates and foreign CPI's are from the International FinanciaJ Statistics of

the International Monetary Fund.

Panel

A

of Table 3 examines the effect of this measure of luck. Note that since the exchange

rate measure can only be constructed for industries where

is

much

smaller here than for our

full

as well as for quadratics in tenure

in millions

and pay

levels

is

and

Column

age.^^

and do not include

(1) uses as

dependent variable the

level

Thus, relative to our standard specification, we

Vcilue of

options granted. Since profits are reported

reported in thousands, the coefficient of .17 in colmnn (1) suggests that

is a current or former ofRcer of the company. A grey director

has substantial business relationships with the company.

that

'*We do not report the

data, the sample size

sample. All regressions control for firm and year fixed effects

(not the log) of cash (not total) compensation.

run this regression in

we have imports

coefficients

is

a

relative of

a corporate

officer, or

on age Jind tenure to save space, but they resemble the

and age.

positive but diminishing effects of tenure

16

someone who

oil indxjstry findings:

SI, 000 increase in profits leads to

now

exercise but

As

pay

for

in the oil case,

for general

Columns

pay

we

for luck:

pay

find a

performance

(3)

through

a 17 cent increase in performance. Column

we instrument

for

performance using the exchange rate

for luck coefficient that is of the

we

(6)

run the more standard regression where we use the logarithm of pay

When

(either total or cash) rises

movements

columns

in

(5)

and

(6)

total assets). In

we use

columns

total compensation.

be about the same as the

find the sensitivity of pay to luck to

to a general shock.

as the

coefficient.

we use only cash compensation, while

In both cases,

shocks.^'^

same order of magnitude

and an accounting measure of performance (operating income divided by

(3) BJid (4)

performs the same

(2)

sensitivity of

pay

accounting performance rises by one percentage point compensation

by about 2 percent, whether that

rise

was due to luck—exchange rate

—or not.

Colmnns

(7)

through

(9) replicate these foiir

colimans but for market measures of performance.

Again, we find pay for luck that matches the pay sensitivity to a general shock.

wealth of one percent leads to a

rise in

pay (again either total or cash) of about

A rise in shareholder

.3

percent irrespective

of whether this rise was caused by luck.

Two important points should be taken away

average firm rewards

its

There seems to be very

CEO

as

little if

much

any

from this panel.

for luck as

filtering.

it

Since

First, to

a first approximation, the

does for a generaJ movement in performance.

we

use a totally different shock, these findings

address theoretical concerns about the use of mean industry shocks (such as those raised in Gibbons

and Murphy (1990) and Aggaxwal and Samwick (1999b)) and shows that the lack of

observed in

RPE

Second, there

^''First

filtering

findings generalizes to other sources of luck.

is

as

much pay

for luck

on

totally discretionary

stage regressions are reported in 'Rible A2. In practice

we use

components of pay

as instruments a set of

indicate any significant exchange rate appreciations or depreciations in the current

are jointly highly significant.

17

and past

dummy

year.

(salary

jmd

variables that

The instruments

bonus) as there

pay

for luck

is

on other components such as options granted. This

arise because firms

might

commit

plans where the number of options grants

is

(implicitly or explicitly) to multi-year stock option

fixed ahead of time.

options rise and so does the value of options grants (Hall, 1999).

subjective

component of pay

for

performance

quite suggestive. Boards are rewarding

3.2.3

Mean

In Panel

mance

B

CEOs

rules out the notion that

sensitivity.

for luck

To

find

As

firm vaJues rise, the prices of

More

pay

bonus

generally,

for luck

even when they could

on

this

is

the most

component

is

filter it.

Industry Movements as Measures of Luck

of Table

we

3,

replicate Panel

of the industry, which

More

firms in the industry.

in a given year,

meant

except that our measure of luck becomes

specifically, as

firm in a given year

to.

to,

an instrument

for firm-level rate of

Similarly, as

by

perfor-

all

the

accounting return

rate of accounting return in that year in the 2-digit

excluding the firm itself from the calculation.^^

the share of

is

mean

to capture external shocks that are experienced

we use the weighted average

industry that firm belongs

the firm belongs

is

A

its total assets in

an instrument

The weight

of a given

the "total" total assets of the 2-digit industry

for firm-level logarithm of shareholder wealth in

a given year, we use the weighted average of the log values of shareholder wealth in the

2-digit

industry in that year, again excluding the firm itself from the calculation and using total assets to

weight each individual

Like in Panel A,

for a quadratic in

firra.^^

all

regressions include firm fixed

CEO

age and a quadratic in

twice the data points of Painel

'*

We

A

CEO

tenure.

because we can now use

also investigated the use of 1-digit

and

3-diglt industry

and year

eflFects

means

The

fixed efiects.

We

also control

regressions include

all firms,

more than

not only those in the traded

as instruments

and found

qualitcitively similar

results.

'^These mean industry performance measures are constructed from

COMPUSTAT. To

the performance measures between Yermaclc's firms and the rest of industry,

income to assets

present in

ratios

from

COMPUSTAT

in

COMPUSTAT

every year,

we

for the firms in

lose

Yermack's. Because not

about 800 firm-year observations.

18

maximize consistency of

we also compute shareholder wealth and

all

firms in Yermack's data aie

B

goods sector. Panel

all

shows a pattern quite similar

specifications again roughly

matches the pay

to

Panel A.

for general

The pay

for luck relationship in

performance. Besides reinforcing the

findings of Panel A, these latest findings suggest that previous

RPE

results arose probably not

because of miameasurement of the reference industry or of the industry shock but because of true

pay

for luck.

Could Pay

3.2.4

for

Luck Be Optimal?

Since the results so far clearly establish pay for luck or a lack of performance filtering,

to ask whether pay for luck could in fact be optimal.

that would generate pay for luck in

we have assumed that o

First,

is

important

for

most of our

an optimal contract?

We

could think of at least three.

contractible. If o cannot be contracted

findings. First,

natural

Are there complications to the agency model

upon or measured

the empirical testa developed in section 2.3 are no longer valid. In practice,

is

it is

it is difficult

we do not

well,

believe this

to believe that non-contracting issues

can

explain our results in the oU industry case study: the price of crude oil can easily be measured ajid

written into a contract. Second, even in the presence of non-contractibility, subjective performance

evaluation should efl'ectively

filter (see

Baker, Gibbons and Murphy, 1994).

subjective performance evaluation relates to

problem

for the

commitment

issues,

for

boards of directors of the large firms we study here.

example to

forecast,

most readily evaluated

oil

respond

to,

may want

to provide to the

or hedge against luck.^^ This kind of argument can be

in our oil industry application.

Suppose a particularly talented

CEO

in the

industry understood the political subtleties of the Arab countries and forecasted the coming of

^'

the

only problem with

but these are unlikely to be a

Second, we have neglected the possibility of indirect incentives one

CEO,

The

An argument similar

CEO

to hedging has been

made by Diamond

(1998).

Tying pay to luck may generate incentives for

would seem to be in the interest

to change his correlation with the luck variable. In practice, diversification

of management

and not

sheixeholders. Tiifano (1996), for

as share or option ownership, are quite predictive of risk

example, demonstrates that managerial characteristics, such

management

19

in

a sample of gold

firms.

the positive

increasing inventories, or intensifying search for

when

here

is

that those

CEOs who were

what we

test for.

as every other oil

may want

to reward

We

he could have increased his firm's profits

is

to reward

them

CEO who

CEOs

responds to the shock exactly the same way

for exceptional responsiveness to shocks, but there

oil

CEO

could be affected by the

human capital

CEOs more

of oil

is little

Again,

reason

random

factor o.

When

CEOs may simply become more

the

valuable.

simply to match their increased outside options. Thus, pay

Some objections can be raised against

CEO human capital should become more valuable as

bad times that having the right

this

view as well. First,

industry fortunes

rise.

it is

unclear

For example,

it

why

may be

CEO is most valuable. A priori, either relationship seems

Second, we have found some evidence of asjonmetries in the pay-for-luck relationship

that are hard to reconcile with that view (and easy to reconcile with a

luck" seems to matter

industry always goes

more than "bad

up when the

price of crude oil goes

it

well.

optimal here not as an incentive device, but merely becatise the optimal level of pay

increases with luck.

plausible.

shock.

for just average responsiveness.

Firms then pay their

exactly in

oil

rise (or fall, for the negative shocks) in pay.

rewarded. This cannot be a reward for having forecasted

industry enjoys good fortune, the

for luck is

CEO? The important point

use none of the firm to firm variation in response to the

results suggest that a

CEO

oil wells,

exceptional in having forecasted should indeed be rewarded. But

Third, the reservation utility of the

oil

wells,

merely test whether the average firm experiences a

Put another way, our

one

new

increasing output from existing

the shock did come. Shouldn't shareholders reward this farsighted

this is not

We

By

shock at the beginning of the 1980's.

oil

luck". For example, average

price of crude oil goes

skimming view). "Good

CEO

compensation

in the oil

up but does not alwaj^ go down when the

down. Also, when we separate positive and negative mean industry shocks,

appears that pay responds more to positive indiistry shocks than to negative industry shocks

20

(while there are no asymmetries in the sensitivity of pay to individual firm performance).^^

Finally,

one might argue that pay

for luck is

a form of risk sharing between

firms are effectively risk averse, perhaps because of liquidity constraints, they

some of the

oil

risks they face

industry study.

awash

in cash

would need

It is

with their

CEO. This argument

hard to imagine why the large

oil

is

CEOs

ajid firms. If

may want

to share

best evaluated in the context of our

producers we study, which are usually

and have excellent bond ratings (perhaps because large holdings of pledgeable

to share risk

take futures positions in

take on the risk than the

with the

oil

CEO. Even

if

these firms needed to lay off risk, they can readily

which would allow them to shaxe the risk with a market better able to

CEO.

Similarly, exchange rate futures

markets are active. Of course, one

could argue that for

mean industry movements

futures markets

But

would then only apply to

this third luck

this explanation

assets),

may

not be as readily available.

measure, whereas our results hold

similarly for all the measures.

While we have provided arguments against these various extensions of the simple agency model,

in the

end we

stiU believe that they merit serious consideration.

for luck finding does not

corporate governance affects

3.3

The

Effect of

We

per se rule out agency models.

CEO

They suggest

to us that the pay

deal with this issue by examining

how

pay.

Governance

The skimming view makes a

further prediction.

Since

it

emphasizes the CEOs' ability to gain

control of the pay process, corporate governance should play

exactly in the poorly governed firms where

process. This suggests that

To examine how pay

we expect CEOs

we should expect more pay

for luck differs

an important

to

most

role in

skimming.

easily gain control of the

for luck in the poorly

between well and poorly governed

It is

pay

governed firms.

firms,

we estimate two

'*These results, not directly reported here, aie available upon request from the authors. They hold quite strongly

accounting measures of firm performance but are not present for market measures of firm performance.

for

21

equations. First, in order to provide a baseline,

differs

(2)

between well and poorly governed firms.

we allow the pay

except that

=

Vit

where Govu

is

+

ai

at

for

we ask how pay

We

performance

for general

estimate an

coefficient to

OLS

performance (not luck)

equation similar to equation

depend on governance:

+ ax * Xu + ao * Govu + 0* perfu + 7 * {Govu

*

perfu}

+

eu

(6)

a measure of governance. To xmderstand this equation, differentiate both sides with

respect to perfu:

dperfit

The

for

7 would imply

Equation

To

CEO

sensitivity of

get at

procediire.'^

that better governed firms

(6) of

pay

course

for luck,

We

pay to performance depends on the governance

tells

we

greater

pay

for

A

positive value

performance.

us nothing about pay for luck, merely about pay for performance.

re-estimate this equation using our two stage instrumental Vcuriables

then compute an estimate of the

mance, 7 and an estimate of the

effect of

Oiu- test then consists in comparing

governed firms

show

variable.

when poorly governed

effect

of governance on pay for general perfor-

governance on pay for luck, ^luck-

7 and

jLuck-

firms display

We

will

speak of more pay for luck in poorly

more pay

for luck relative to

pay

for general

performance. If poorly governed firms simply gave more pay for performance and pay for luck rose

as a consequence,

is

pay

we would not

for luck that

refer to this as

more pay

for luck. In practice,

we

will see that

it

changes with governance, while pay for performance hardly changes.

^"'An extremely important caveat here:

a different responsiveness of performance

to instrument, appears both directly and

we perform two first stages, one for the

procedure is cruciaJ because it allows the

our approcich allows for the possibility that better governed firms may have

to luck. Technically, performance per fa, the endogenous variable we need

indirectly (the term Govit * perfu) in this equation. ^Vhen we instrument,

direct effect

perfu and one for the interaction term GotHt

on performance to depend on governance.

effect of luck

22

*

ptrfu- This

Large Shareholders

3.3.1

In Table

4,

we implement

this

framework

We

for the case of large shareholders.

presence of large shareholders affects pay for luck. Shleifer and Vishny (1986),

that large shareholders improve governance in a firm.

A

single investor

who

ask whether the

among others, argue

holds a large block of

shares in a firm will have greater incentives to watch over the firm than a dispersed group of small

shareholders.'^ In our context, the idea of large shareholders

our

intiiition of

most naturally as

this

matches

"having a principal around." Yermack data contains a variable which counts the

who own

nimiber of individuals

further

fits

know whether

blocks of at least 5 percent of the firm's

these large shareholders are on the board or not.

that large shareholders

A

common

priori,

on the board have the greatest impact. They can exert

shares.^^

We

one might expect

their control not just

through implicit pressure or voting, but also with a direct voice on the bocird. Since the information

available,

is

The

AU

we

first

will consider the effect of

both

four columns of T^ble 4 use

regressions include the usual controls.

performance depends on governance

for

all

large shareholders

and of only those on the board.

aU large shareholders as our measure of governance.

Column

(1) estimates

how

the sensitivity of pay to

accounting measures of performance.

The

first

row

tells

us

that a firm with no large shareholders shows a sensitivity of log compensation to accounting return

of 2.18.

An

increase in accounting return of one percentage point leads to

about two percent. The second row

tells

in

pay of

us that adding a large shareholder only weakly decreases

the sensitivity of pay to general performance, and this effect

example, a one percentage point increase in accounting retm^i

in

an increase

is

not statisticadly significant.

now

For

leads to a 2.09 percent increase

pay when the fixm has one large shareholder and not a 2.18 percent increase in pay. Colmnn

They

also point out

a possible opposite

rents for thenaselves. This effect

"Whenever CEOs happen

to

is likely

effect:

very large shareholders

may have a

greater ability to expropriate

to be greatest in other countries where investor protection

own such a

block,

we exclude them from the count.

23

is

weakest.

(2) estimates

there

how

pay

significant

is

pay

large shareholders affect

for luck.

for luck.^

The second row here

As

row

before, the first

tells

tells \is,

however, that this pay for luck

A

one percentage point increase in

diminishes significantly in the presence of a large shareholder.

accounting returns due to luck leads to roughly a 4.6 percent increase in pay when there

shareholder but only a 4.2 percent increase in pay

when

additional large shareholder decreases this effect by

.4

us that

there

is

is

no large

one more large shareholder. Each

percent. This

is

a 10% drop in the pay for

luck coefficient for each additional large shareholder.

Columns

,/;

(3)

In this case, the

estimate the same regressions using market measures of performance.

and

(4)

pay

for general

performance does not depend at

shareholder (a coefficient of .001 with a standard error of .007).

diminishes with the presence of a large shareholder.

for luck

10%

the

for

level,

the economic magnitude

is

The pay

larger.

aJl

We

WhUe

on the existence

of a large

again find, however, that pay

the result

for luck coefficient

is

only significant at

now drops

^ « 17%

each large shareholder.

In columns (5) through {8)

We now

focus only

on

we repeat the above

exercise but altering the governance measure.

Comparing columns

on the board.

large shareholders

(6)

and

(2),

we

see that the governance effect strengthens significantly with respect to the filtering of accounting

performance.

The

We see that the pay for luck drops by 33 percent for each additional large shareholder.

results are very statistically significant.

also rises

but

less dramatically.

In column

On

(8),

market performance measures, we find the

effect

the pay for luck drops 23 percent with each large

shareholder on the board. Moreover, this last result

is

insignificant. In

summary, our findings

in

Table 4 highlight how large shareholders (especially those on the board) affect the extent of pay

for luck.

*In

all

powerful

Firms with more large shareholders show

that follows,

first

we

stages in the

far less

use mean industry performance as

IV framework.

will

24

pay

otir

for luck.

measure of luck since this produces the most

Entrenchment and Large Shareholders

3.3.2

The

results in

CEO

the effects of

CEOs who

Table 4 simply compare firms with large shareholders to firms without. This ignores

pay

governance

belief

is

that

have been with the firm longer have had a chance to become entrenched, perhaps by

appointing friends on the board.

greatest

A common

tenure, another important determinant of governance.

for luck.

we

woxild expect high tenure

Moreover, we would expect this

weak and there

is

In this case,

no large shareholder present

is

Hence, in the absence of large shareholders, we expect

be strongest

effect to

fairly

CEOs

to

show the

in those firms

where

to limit the increased entrenchment.

CEO's

strong governance early in a

tenure but this governance should weaken over time as he entrenches himself. In the presence of

large shareholders,

we not only expect stronger governcince but

shoidd last throughout the

there

is

CEO's

tenure. It

is

CEO

harder for a

a large shareholder aroimd. Thus we expect a

aJso that this stronger governance

rise in

pay

to begin stacking the

for luck

board when

with tenure in the absence

of a large shareholder, but less of a rise (or even no rise) in the presence of a large shareholder.

T^ble 5 tests this idea.

We

first

sort firms into two groups based

on whether they have a

large shareholder present on the board.^^ This produces 740 or so data points for firms with large

shareholders and 3880 or so data points for firms without large shareholders. For each

separately estimate regression 6 for these

Columns

(1)

shareholder.

^5^

w

with columns

^We

(2) focus

The second row

greatly increases

about

and

pay

35%

(3)

for luck. In fact, a

(4)

of performance in firms without a large

us that while tenure does not affect pay for performance,

CEO

with (roughly) the median

greater pay for luck than one

and

we now

two groups with tenure as our governance measure.

on accounting measures

tells

set,

who just began

which estimates the same

effect for firms

teniure of 9 years

shows

at the firm. Let us contrast this

with a large shareholder present.

focus only on large shajeholdeis on the bojird because these provided the strongest results in Table 4.

have used

aJl

large shareholders

and found

similar,

though

statistically

25

it

weaker, results.

We

Here we find that tenure does not

for

performance

slightly. '^°

pay

affect

Thus pay

for luck at all, while, if

for luck increases with tenure

anything,

it

seems to

pay

raise

without large sliareholders but

does not change with tenure with them.

Columns

(5)

through

repeat the tests of columns (1) through (4) but for market measures

(8)

of performance. Here the results are less stark but

and

(5),

we

see that both pay for performance

rises three times as fast (.003 versus .009).

significant at the

10%

level.

The economic

both diminish with

3.3.3

(7),

we

and pay

The

very suggestive. Comparing columns

for luck rise

coefficient

with tenm-e, but pay

on the pay

see that

=^^^ « 31% but a

if

rise in

a

pay

(6)

for luck

for luck, however,

significance however stays large as

of 9 yeaxs shows an increase in pay for luck of

only 10%. In columns (8) and

still

only

is

CEO with a tenure

for

performance of

anything pay for luck and pay for performance

teniu-e.

Other Governance Measures and Robustness Checks

While large shareholders correspond most

closely to the idea of

a principal, other governance

measures could also be used. Our data contain two variables that have shown to be important

governance measures in the past: the size of the board and the fraction of board members that are

insiders in the firm.^'^ Small boards are thought to

(1996), for example,

be more

shows that smaller boards correlate with larger q values

four columns in Table 6 estimate the effect of board size

that for accounting measures, the direction of the effect

the coefficient

'^Gibbons

effective at governing firms.

is statisticcilly

axid

Murphy

also

examined

insignificant.

on pay

is

CEOs

Columns

the opposite of

Note that the actual

(1992) present evidence that

for luck.

for firms.

(1)

and

Yermack

The

(2)

first

show

what we postulated but

size of the coefficient is tiny:

even a

with longer tenure have greater pay for performance

generally.

^*We have

CEO

ownership and whether the founder is present. We do not report these for space

effects. Founders and CEOs with high insider ownership both show

reasons but both produce genercJIy significant

greater pay for luck.

26

huge increase

and

(3)

(4),

in

board

size of 10

board members leads only to a

however, show that there

and these are of the expected

cire

significant effects for

The

6.

a drop of

'^'^^^j^^-

» 30%

in the

pay

other measure we examine

The

is

But,

coefficient of .228.

(6)

it

The

shows a pay

directors

for

10%

is

for luck coefficient of .177.

is

This represents

a measure of insider presence on the board. This variable

level).

negative and small.

directors.

Columns

insider presence dramatically increases the

pay

(5)

for luck

In a board with ten directors, turning one of the outside

from an outsider to an insider increases pay

performance

show a pay

smaller board continues to

for luck coefiicient.

show that on accounting measures,

coefficient (significant at the

Columns

market measures of performance

measured as fraction of board members that are firm insiders or grey

and

for luck.

big board firm shows a pay for performance

coeSicient of .240 and a pay for luck coefficient of .229.

performance

drop in pay

Consider the difference between two boards, one of which

sign.

has 10 board members and one of which has

for

2%

Columns

(7)

by

for luck

and

(8)

^l^*'^

^

20%. The

effect

on pay

show that on market performance

measures, insider board presence again increases pay for luck, but while the coeflacient continues

to be economically large

We

turn to our

last

index that aggregates

all

it is

statistically quite insignificant.

where we construct an

governance measure in columns

(9)

through

the governance measures \ised so

far:

number of large shareholders, number

(12),

of large shareholders on the board, board size and insider presence on board.

we demean each

take the

sum

of the four govemEince variables, divide

it

of these standardized variables. For bocird size,

procedure. For fraction of insiders on the board,

by

its

we use negative of board

we use one minus

*'This particular

way

index,

standard deviation, and then

size in this

that fraction. This guarantees

that the resulting governance index has larger values whenever the firm

and once as generaJ

To form the

is

better governed.^'^

of proceeding will tend to count large shareholders on the board twice, once as on the board

is a crude way of incorporating our prior belief (supported by the findings

l^ble 4) that large shareholders on the board matter more. When we use either measure in the index alone, we find

qualitEktively similar results. We have also estimated a regression in which we include all four governance measures

large shareholders. This

in

27

For accounting measures of performance (columns

(9)

and

(10)),

we again

find that

luck diminishes with the governance, wliile pay for performance does not change.

however,

10%

only significant at the

is

level.

To gauge

and

~

^^^

^^^^ ^^

^^^ P^y ^^^

(12)), increase in the

When we

^^*'^ coefficient.

bigger.

A

Finally,

is

that

5%

level.

for firm size.

affects

effect for a

pay

governance "effect."^^

for luck

One might worry

for luck sensitivities, the estimates

A

by 26%.

that large firms have

7,

we address

this

is

problem by controlhng

for size interacted

*

may pay

(5)

through

(8) of

Table

4.

We see

the filtering of accounting rates of return in fact strengthens

versus —1.48).

The

effects

We

per fa. Omi measure of size in these

average log real assets of the firm over the period.

compared to columns

less for luck.

with performance.

We

investigate

measures: large shareholders on the board and the governance index.^^ Colunms

are to be

size

concrete version of this problem might arise in the risk sharing

re-estimate equation 6 but this time include a term Size

regressions

If this

above might confuse this

hypothesis above. If larger firms are simply more able to bear risk then they

In Table

for

Moreover their magnitude

quite different pay for performance sensitivities than small firms (Baker and Hall, 1999).

also translates into different

pay

The primary concern one might have

investigate the robustness of our findings.

we have not adequately controlled

to a

use market measures (columns (11)

one standard deviation increase in governance decreases pay

we

coefficient,

Such an increase leads

2.

governance index greatly reduces pay for luck but hardly