POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS IN RURAL DRINKING WATER PROVISION: by

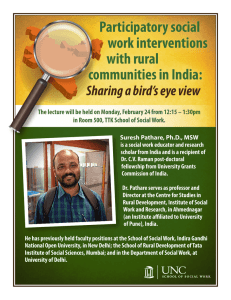

advertisement