Inhabiting the virtual city: Judith Stefania Donath

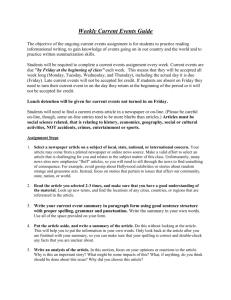

advertisement