THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN HOUSE AS A by

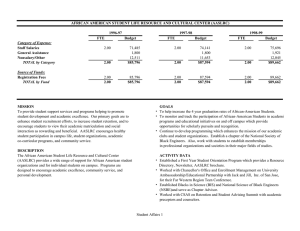

advertisement