SEP 16 PIS 2010 7

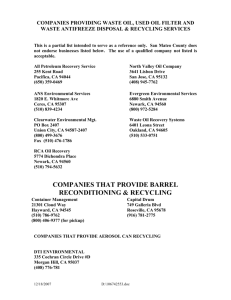

advertisement