Document 11131907

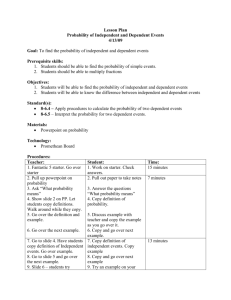

advertisement