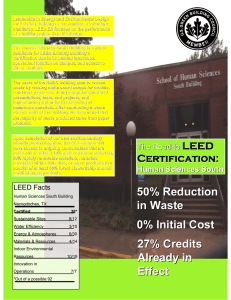

Greening Existing Buildings with LEED-EB!

advertisement