The Neighborhood Main Street Initiative in the Barrio:

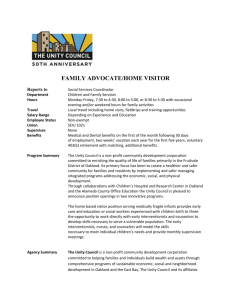

advertisement