The Power of Partnerships: Transforming Students and Communities through Service-Learning 2 0 11

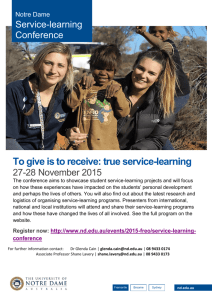

advertisement