QUEENSBOROUGH COMMUNITY COLLEGE/CUNY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INDIVIDUAL COURSE ASSESSMENT REPORT

advertisement

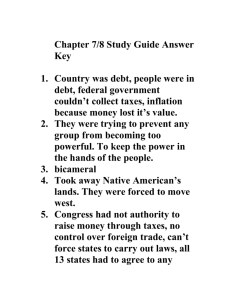

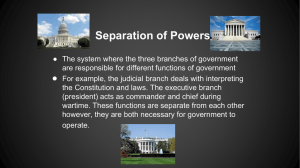

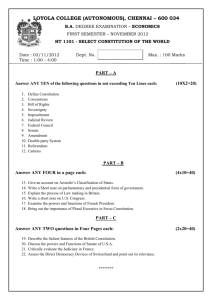

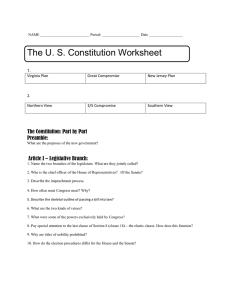

QUEENSBOROUGH COMMUNITY COLLEGE/CUNY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INDIVIDUAL COURSE ASSESSMENT REPORT Date Submitted: 3/10/2015 Course No./Title: PLSC 101 / Introduction to American Government and Politics Course Description: This course offers in depth study and analysis of American government, its historical and intellectual origins and development, with special consideration of its structure and operations, functions of the President, Congress, and judiciary, and the role of government and politics in modern industrial society. Pathways Flexible Core Student Learning Outcome Assessed: -Evaluate evidence and arguments critically or analytically. More specifically: Students were given a short reading assignment in which the main outlines of the American constitutional blueprint for government were presented. Students were then asked 16 multiple choice questions that ranged in difficulty from the merely descriptive to those that required significant critical evaluation, requiring deduction, leaps of logic, and tracing implications from principles to examples. Participants: 1 section: 81 students Course Assessment Method: A reading was assigned (See Appendix 1), after which students were given a 16 question multiple choice quiz (see Appendix 2) based on the reading, and scores were derived consistent with a reading rubric (see Appendix 3). Rating Criteria Emerging 0-1 Correct Constructing Meaning: Questions 1-4 Contextualizing: Questions 5-8 Using Other Perspectives & Positions: Questions 912 Evaluating Evidence and Drawing Conclusions: Questions 13-16 Total Weak Development 2 correct Strong Development 3 correct x x x x x 1 Mastery 4 correct % correct (category average) 43, 52, 50, 100 (61%) 93, 74, 79, 79 (81%) 76, 76, 86, 76 (79%) 83, 69, 86, 69 (77%) 75% Discussion/Action Plan The results were actually somewhat surprising to me, but not discouraging. My students scored the lowest (61%) on the most basic “constructing meaning” category, which is the closest to rote memorization and the least likely of the four categories to tap into higher analytical or deductive reasoning. The scores were highest on the “contextualizing” category, which encourages me that I at least helped them grasp some of the broader brush strokes of the US constitutional systems’ complexity. Scores then fell a bit when students were asked to use other perspectives/positions (79%) and evaluate evidence and draw their own conclusions (77%), though it should be kept in mind that, encouragingly, these were still better results than on the “constructing meaning” section. What this tells me is that while my students may not be absorbing all of the factual content that I would like them to, they are at least performing better on the core critical/analytical component of this learning outcome. In terms of an action plan, clearly there are certain factual areas (“constructing meaning”) that I have to decide on in terms of their worth as testable items, in contrast to what I believe are the more useful and broadly educational goals of the other categories. If only half of my students can remember which powers are enumerated, concurrent or reserved, I have to decide if drilling more on this knowledge is worth perhaps losing some focus in terms of helping them see the complexity of the “big picture” and drawing independent inferences therein. Appendix 1 – Assigned Reading The Constitutional Convention reached a set of compromises, termed the Great Compromise, that provided for a bicameral legislature featuring an upper house based on equal representation among the states and a lower house whose membership was based on each state’s population; approved by a 5–4 vote of the state delegations. Its critical features included 1. a bicameral (two-house) legislature with an upper house or “Senate” in which the states would have equal power with two representatives from each state, and a lower House of Representatives in which membership would be apportioned on the basis of population. The Great Compromise also resolved disagreement over the nature of the executive. The agreement reached called for the president (and vice president) to be elected by an electoral college. As chief executive, the president would have the power to veto acts of Congress, make treaties and appointments with the consent of the Senate, and serve as commander-in-chief of the nation’s armed forces. Constitutionally, the vice president is first in line to succeed the president in the event of death or incapacitation. By statute, if the vice president is not available to serve, succession falls in turn to the Speaker of the House, the president pro tempore of the Senate, and then to cabinet-level officials. Recognizing that calls for fairer representation of colonists’ interests lay at the heart of the Declaration of Independence, popular sovereignty was a guiding principle behind the new constitution. The document’s preamble beginning with “We the People” signified the coming together of people, not states, for the purposes of creating a new government. Under the proposed constitution, no law could be passed without the approval of the House of 2 Representatives, a “people’s house” composed of members apportioned by population and subject to reelection every two years. The delegates also recognized the need for a separation of powers (The principle that each branch of government enjoys separate and independent powers and areas of responsibility.) The Founders drew upon the ideas of the French political philosopher Baron de Montesquieu, who had argued that when legislative, executive, and judicial power are not exercised by the same institution, power cannot be so easily abused. Mindful of the British model in which Parliament combined legislative and executive authority, the drafters of the new constitution assigned specific responsibilities and powers to each branch of the government—Congress (the legislative power), the president (the executive power), and the Supreme Court (the judicial power). Although united by the belief that the national government needed to be strengthened, the framers of the new constitution were products of a revolutionary generation that had seen governmental power abused. Thus, they were committed to a government of limited or enumerated powers (Express powers explicitly granted by the Constitution, such as the taxing power specifically granted to Congress.) The new constitution spelled out the powers of the new federal government in detail, and it was assumed that the government’s authority did not extend beyond those enumerated powers. The powers retained by the states are reserved powers (Those powers expressly retained by the state governments under the Constitution.) And the powers shared by the federal and state governments are generally referred to as concurrent powers (Those powers shared by the federal and state governments under the Constitution.) 3 Article I, Section 8 enumerates the specific powers held by the national legislature. Among these are economic powers such as the authority to levy and collect taxes, borrow money, coin money, and regulate interstate commerce and bankruptcies; military powers such as the authority to provide for the common defense, declare war, raise and support armies and navies, and regulate the militia. Overlaying this explicit system of enumerated powers for Congress and reserved powers for the states is the supremacy clause of Article VI, which provides that the Constitution and the laws passed by Congress shall be “the supreme law of the land,” overriding any conflicting provisions in state constitutions or state laws. The supremacy clause gives special weight to the federal Constitution by ensuring that it cannot be interpreted differently from state to state. In the landmark case of Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Virginia Supreme Court’s attempt to interpret the federal Constitution in a way that conflicted with the U.S. Supreme Court’s own rulings. Accordingly, each state legislature and state judiciary not only must abide by the terms of the federal Constitution, it must also abide by the interpretation of those terms laid out by the U.S. Supreme Court. The provisions listed in the Bill of Rights enjoyed little influence in late-eighteenth-and earlynineteenth-century America, because they were understood to be restrictions on the federal government only. That all changed in the twentieth century, as the Supreme Court grew increasingly willing to protect individuals against intrusive state actions. Its instrument for doing 4 so was the Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868), which provided that no state could “deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment had been passed immediately after the Civil War to protect freed slaves from discriminatory state laws. Yet at the beginning of the twentieth century and increasingly throughout the century, the Supreme Court, by a process known as incorporation, used the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to make most of the individual rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights also applicable to the states. Congress also has the authority to impeach and remove federal judges, cabinet officers, the president, the vice president, and other civil officers. The removal process requires an impeachment action from the House and a trial in the Senate. Impeachment is the formal process by which the House brings charges against federal officials. A judge, president, or executive official who is “impeached” by the House is not removed; he or she is charged with an offense. In this sense, the House acts as an initial forum that makes the decision about whether a trial is warranted. An impeachment occurs by a majority vote in the House of Representatives. An official may be impeached by the House on more than one charge, each of which is referred to as an article of impeachment. Assuming the House passes at least one article of impeachment, the official must then stand trial in the Senate. A two-thirds vote of the full Senate is required for removal of an official. Appendix 2 – 16 Multiple Choice Questions on Constitutional Reading Constructing Meaning 1. The power to establish bankruptcy laws is an example of: a. An enumerated power. b. A reserved power. c. A concurrent power. d. A dictated power. 2. The power to conduct elections is an example of: a. An enumerated power. b. A reserved power. c. A concurrent power. d. A dictated power. e. A revealed power. 3. The power to coin money is an example of a(n) a. enumerated power. b. reserved power. c. concurrent power. d. dictated power. e. revealed power. 4. When a judge, president, or executive official is impeached, that person is 5 a. charged with an offense. b. assigned to a lower position. c. removed from office. d. sent to federal prison. Contextualizing 5. Which of the following is NOT one of the constitutionally expressed powers of the president? a. power to grant reprieves or pardons b. commander in chief of the armed forces c. power to make certain appointments d. power to approve treaties 6. Powers shared by federal & state governments are called: a. enumerated powers. b. reserved powers. c. concurrent powers. d. moderate powers. 7. The Constitution spelled out the powers of the new federal government in detail, and it was assumed that the government's authority did not extend beyond those powers known as the ________ of the federal government. a. loose construction b. separation of powers c. checks and balances d. enumerated powers 8. According to the Constitution, while the vice president is first in line to succeed the president in the event of death or incapacitation, if the vice president is unable to serve then succession falls to a. the Speaker of the House. b. a cabinet-level official. c. the minority whip. d. Congress. Using other Perspectives and Positions 9. When the founders established ________ in the new government, they drew upon the ideas of Baron de Montesquieu, who had argued that when legislative, executive, and judicial power are not exercised by the same institution, power cannot be so easily abused. a. federalism b. enumerated powers c. checks and balances d. separation of powers 6 10. The "Great Compromise" resulted in a ________ and satisfied the representational conflict between small states who wanted equal representation in the Senate and large states who wanted representation based on population in the House of Representatives. a. joint committee b. bicameral legislature c. two-party system d. unicameral legislature 11. The ________ Amendment applied the Bill of Rights to the states when it declared that no state could "deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law." a. Eleventh b. Fourteenth c. Sixteenth d. Twentieth 12. If Arizona passes an immigration law in conflicts with federal law, the federal law overrides any conflicting provisions due to: a. the privileges and immunities clause. b. the supremacy clause. c. the doctrine of preemption. d. concurrent powers. Evaluating Evidence and Drawing Conclusions 13. Who makes the determination that a particular action or law is in violation of the free exercise clause of the 1st Amendment? a. state legislatures b. Congress c. the president d. the U.S. Supreme Court 14. When the U.S. Supreme Court makes a ruling concerning the interpretation of the Constitution: a. the supremacy clause does not apply to that ruling b. any state legislature or state court must also abide by the interpretation of the Constitution made in the ruling c. that ruling may be overridden by a state's supreme court. d. that ruling has no bearing on state governments. 15. In the U.S. House of Representatives, membership from each state is based upon a. political party strength. b. appointment by the governor. c. equal representation from each state. d. population of the state. e. amount of funding allotted by the previous Congress. 7 16. The Constitution requires that members of the House serve a ________ term, keeping them constantly attentive to the currents of public opinion. a. six-year b. four-year c. three-year d. two-year 8