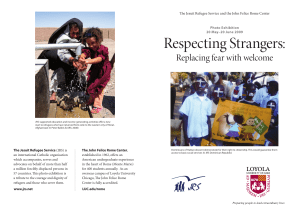

Recreating Right Relationships DEEPENING THE MISSION OF RECONCILIATION IN THE WORK OF JRS

advertisement