E

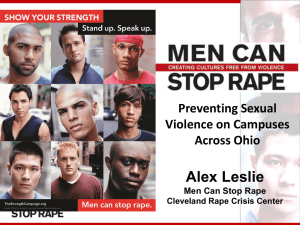

advertisement