Big Business Works with Small ...

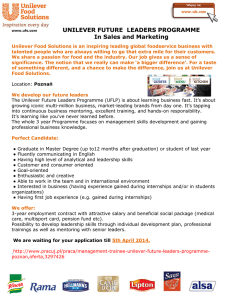

advertisement