Document 11085843

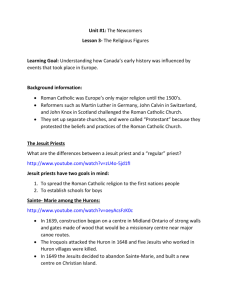

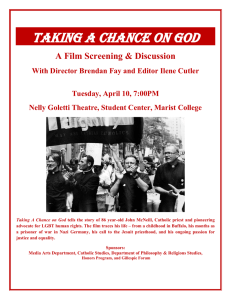

advertisement