Women’s Experience of Income Management in the Northern Territory

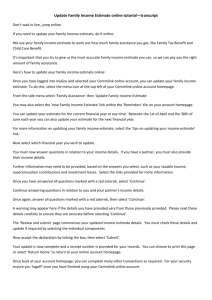

advertisement