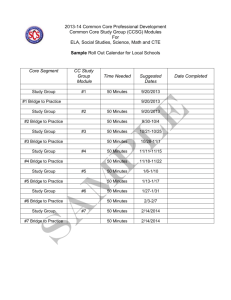

Bridge to College Math and Bridge to College English Progress Report

B A K E R E V A L U A T I O N R E S E A R C H C O N S U L T I N G

P R O G R E S S R E P O R T

J u n e 2 0 1 5

Bridge to College Math and Bridge to College English Progress Report

Prepared for the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges, Office of the

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and College Spark Washington

DUANE BAKER, Ed.D

CANDACE A. GRATAMA, Ed.D.

SARAH C. BRENNER, M.Ed.

RACHEL S. GREMILLION, M.Ed.

Duane Baker is the founder and president of Baker Evaluation, Research, and

Consulting, Inc ( The BERC Group ). Dr. Baker has a broad spectrum of public school educational and program experience, including serving as a high school classroom teacher, high school assistant principal, middle school principal, executive director for curriculum and instruction, and assistant superintendent. In addition, he has served as an adjunct instructor in the

School of Education at Seattle Pacific University since 1996, where his emphasis has been Educational Measurement and Evaluation and Classroom

Assessment.

Dr. Baker also serves as the Director of Research for the Washington School

Research Center at Seattle Pacific University. He also serves as an evaluator for several organizations including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,

Washington Education Foundation, Washington State Office of

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and others.

Members of The BERC Group have K–20, experiences as teachers, counselors, psychologists, building administrators, district administrators, and college professors. The team is currently working on research and evaluation projects at the national, state, regional, district, school, classroom, and student levels in over 1000 schools in Washington State and nationally.

THE BERC GROUP

COPYRIGHT

©

2015 BY THE BERC GROUP LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS REPORT MAY BE OBTAINED THROUGH THE BERC GROUP

(www.bercgroup.com).

COPYRIGHT © 2007 BY THE BERC GROUP LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS REPORT MAY BE OBTAINED THROUGH THE BERC GROUP (www.bercgroup.com).

Table of Contents

THE BERC GROUP

THE BERC GROUP ii

Bridge to College Math and Bridge to College

English Progress Report

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this report is to provide formative feedback to the State Board of Community and

Technical Colleges (CBCTC), the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), and

College Spark Washington regarding evidence of implementation of the Bridge to College Math

(BTCM) course and the Bridge to College English Language Arts (BTCELA) course during the

2014-2015 school year, the pilot year of the program. The report, while addressing initial implementation efforts, is also designed to provide stakeholders with formative feedback to assist in ongoing program development. A description of the evaluation design, evaluation findings, and discussion and conclusions follow the introductory section. The report concludes with recommendations drawn from the evaluation.

The State Board for Community and Technical Colleges plans to create and implement senior year college readiness math and English courses that align with the Common Core State Standards and with pre-college courses in higher education. The courses will be developed collaboratively with high school and college faculty, and seniors who complete the transition courses with a B level grade will be able to move directly to college level math and English courses without remediation or additional placement testing. The course will be designed for students scoring a Level 2 on the

Smarter Balanced Assessment.

Thirty-seven English teachers and 16 math teachers signed up to pilot the Senior Year Transition

Courses in the 2014-2015 school year; however, some opted out after agreeing to pilot the program. In total, 120 additional sites plan to be added by Year 2, and 150 sites plan to be added by

Year 3. The goal of the project is to improve college readiness of students graduating high school, to develop college to school partnerships, to reinforce transcript placement efforts with the

Smarter Balanced assessment, and to provide rigorous alternatives to algebra 2 as the third year math course.

EVALUATION DESIGN

Evaluation Questions

Evaluation activities followed the existing framework as stated in the original proposal. However, for this progress report, we selected a few questions that were most relevant to the pilot, specifically focusing on implementation efforts. The questions of focus for this progress report include:

1 T H E B E R C G R O U P

Evaluation Questions

1.

To what extend was the initiative implemented as intended?

2.

What are some strengths and barriers/challenges to implementing the initiative?

3.

To what extent did the technical assistance support implementation?

4.

What organizational changes are required for, or correlate with, successful project implementation?

5. To what extent do the initiatives impact student outcomes?

Data Sources

To address the research questions, The BERC Group, Inc. completed the following evaluation activities:

Interviews and Focus Groups with participating teachers for both math and English, as well as school-based administrators and students at schools implementing BTCM.

Interview comments are woven through the report. For readability purposes, grammar has been altered in some cases.

General Data Collection, including initiative documents

STAR Protocol observation and analysis of findings for BTCM

Please note, the initial evaluation was more comprehensive for math, because teachers agreed to teach the entire course. In contract, teachers agreeing to pilot BTCELA implemented one or two modules, rather than the entire course.

EVALUATION FINDINGS

Bridge to College Math

The Bridge to College Math program has been a work in progress. A group of high school teachers have been working with SBCTC, OSPI, a team of local state college and community college professors, and high school teachers to create a program based on the SREB (Southern Regional

Education Board) Readiness Courses and other math curricula to best fit Common Core State

Standards, Washington State graduation requirements and college acceptance requirements. There is still much tweaking being done during this pilot year and the participating high school teachers continue to collaborate via meetings and through an online forum to share their supplemental materials and assessments.

Teachers, administrators, and students alike praised the program, saying engaging and hands on materials help students to learn math through the use of real world applications. Many student interviewees suggested this course has helped them to feel more confident in math and has promoted a deeper level of critical thinking skills. Some of the challenges teachers reportedly are facing include differentiating to a variety of skill levels, creating course assessments, supplementing lessons, and determining how to grade for next year. Next year, the course will be available for senior level students (only) and participating students will be are required to obtain a B in the course in order to be eligible for college level math placement. Teachers are discussing if they need

T H E B E R C G R O U P 2

to create common assessments and how to ensure their grading is similar across the board. This job proves especially complex since some of the schools are on a standards based grading scale and some use traditional grading.

Schools across the state used a variety of methods to identify students for the class during the pilot year. In some cases, both 11 th and 12 th graders who preferred to take Algebra II without the Trig component were allowed to take the Bridge to College Math course. While some of the students claim they are not college bound, some suggested they “just wanted to try a new math course.”

Because students were not admitted based on any types of scores (during this pilot year), some teachers indicated they have had a challenging time accommodating all skill levels. Next year, school members hope to use SBAC scores to better determine which college bound seniors they will invite into the course. According to administrators, scheduling of this class is also a little tricky and requires further attention. These issues are further explored below.

Evaluation Question #1: To what extent was the initiative implement as intended?

Math teachers piloting the program this school year played a variety of roles ranging from lesson creator, cohort collaborator, and instructor. Over the course of the year, teachers also took on the roles of curriculum adjustors and finders of supplemental materials. For the most part, teachers interviewed suggested they have implemented the proposed lessons with little to no supplementations (based on the unit). Some teachers indicated they had to supplement certain lessons so to better scaffold student learning in order to advance to next level course work. “Part of the standards is to use logarithms, but there is no unit on that, so I created one,” shared one teacher, “We are finding that our curriculum has some holes that we have to fill to address the standards.” Other interviewees suggested attention to program pacing would benefit future program participants. One teacher shared their experience saying,

The unit we’re in right now is quadratics. The pacing in the unit is off … part of that is that

I might not have the perfect audience for this. This year I won’t be able to finish because I stopped to take some time for them to understand some critical topics.

When asked how they would improve the program, student focus group members suggested they

“would order it differently so that it aligns and flows with each other.” One teacher identified a challenge around expectations to supplement lessons but suggested teacher trainers may help to clarify such concerns next year. As stated,

With the pilot, I was not sure how they wanted me to flow through the course. I like to create and add things. I didn’t know how much to add in the forums, how open they are to contributions. I’ve met with five or six people in our core group; I had a lot of modifications. They opened up a position for someone to lead those things. Next year, we will have teacher trainers to help show how to base mathematical practices in a genuine way, how to lead activities, and when to let students struggle.

Some interviewees suggest the curriculum itself needs to be revamped so to better integrate technology. One teacher stated,

3 T H E B E R C G R O U P

I’m a big proponent of technology in the classroom, it leads to inquiry. This curriculum does a decent job of incorporating some technology with the website. As far as investigations, they could be revamped. … Technology, if you want students to buy in, we have to be speaking their language. That is their goal, to have something in here where they can investigate differently. To stick around for the long term, it needs to be strengthened.

Students and teachers praised the lessons for integrating “real world” application (i.e.: in the

Exponential Functions units observed, questions revolved around saving money for retirement, illegally introducing fish into lakes, investing money into a bank account, purchasing a car and determining a down payment, calculating the interest rate of a savings account, and figuring out a credit card balance over time with X APR rate). However, both groups also suggested the lessons would benefit from further modification. One student praised the course, saying, “I’m finally getting math and its information I’ll actually use!” However, some students found the real world examples to be antiquated and in need of revision. One student shared, “It needs more realistic story problems. It’s hard to get interested in something like vintage coins.” Another student agreed with this sentiment adding, “They need to make it more applicable to our generation. For instance, don’t talk about digging holes for telephone poles, but [talk about] satellites.” Focus group members also liked that lessons promote critical thinking in a practical way. Students especially seemed to like the project based learning approach of some of the lessons, and suggested the need for “more physical activities.” “The Gummy Bear Parabola project was fun! I feel school should be a hands on experience in general. We should be getting up to do things. Hands on activities are always good. Action speaks louder than words,” lamented one student.

Overall, program participants seem to understand this year was a pilot year and worked to address challenges. Although it has only been one year, many interviewees suggested the course has made a positive impact on students. One teacher discussed the impact the program has made at their school saying,

It’s enriched our math program. The book didn’t make them think; it was drill and kill.

This added all the enriching activities. That’s why I begged to get into the course; it was what our program needed. It’s about getting students to stop and think and not just look at math as a formula. We finally found something kids can use.

Evaluation Question #2: What are some strengths and barriers/ challenges to implementing the initiative?

Interviewees helped to identify some emerging strengths as well as challenges they faced over the course of program implementation this year. These ideas are explored below.

Program Strengths

Involvement of college personnel. When asked to identify elements leading to successful program implementation, multiple stakeholders suggested the collaboration of educators from different

T H E B E R C G R O U P 4

levels as a key element of their success this year. Local and community college professors and representatives have actively collaborated with high school teachers and program staff to create lessons and to monitor course progress. One person shared their journey with the program stating,

When this first started, it was all community college and college people, and only four high school people … that’s where it needs to be, the buy in has to be with the colleges. They have been driving all of this stuff. We identified what are the big ideas based on ‘what do you want students coming out of high school to have?’ That drove the discussion. What skills do we want high school kids to have? The Community College folks said to go through standards and match the skill set that colleges want kids to have, and at what level.

We came up with set of standards, then developed the program. The reality is - colleges have driven the whole idea of the course. I’m excited to see where it goes!

An administrator supported this sentiment, saying, “I think it’s great we are finally working on articulation with colleges. If we don’t do a Kindergarten through 16 model, the whole thing will crumble. This program is pretty rigorous, too rigorous for some, but if you set the bar high, kids rise to it.”

Collaboration among participants . Interviewees praised the ability to collaborate with other teachers and program staff through face-to-face meetings, during trainings, or through the online portal. One teacher shared, “They have been so awesome about getting us together to talk about

[the course], to adapt the curriculum, modeling the hooks, and to discuss the assessment pieces. I am learning by working with the team.” Another interviewee discussed how support from other pilot teachers and program coordinators has enhanced their experience, saying,

It’s so nice to have a group of people all working on same things this year with so much support. It’s nice to have other schools involved, especially [local schools]. We talk about assessments, where we are each at with the lessons, and what [other teachers] added or changed. It’s been a collaborative effort, for sure.

Engaging, applicable material . As previously mentioned, a majority of stakeholders indicated the program is helping to transform student perceptions about math due to the engaging, hands on, and applicable course material. An administrator praised the course, saying,

The kids are engaged in this curriculum with this program. We have not seen that except with our top, top teacher who knows how to connect with kids. They are engaged because the curriculum is strong, and they see a goal for their future with college. When you have a goal to shoot for, a possible reward, you will get motivation.

Teachers interviewed discussed the attraction of making course materials not only applicable to student life but engaging and hands on, with one teacher sharing,

Bridges brings math to life. It uses the information; it’s not just hands on, but all the applications of how to use the math. Everything comes to life and now we can see the math involved. Shooting gummy bears, now you think about how to make it go far, high. Five

5 T H E B E R C G R O U P

dollars in gummy bears goes a far way. … They get to see the fun in math. I didn’t learn that way. There is so much more in life, math is everywhere. You maybe had one or two hands on lessons in past, but with this one, every unit has a come to life activity. If every teacher were doing these kind of lessons- wow!

Students also shared their opinion about the course, with multiple students praising the way it “tries to bring math into more relevant real life.” One student mentioned,

Some people may think ‘what’s the purpose of math?’ but if you are a construction worker, then math is really important. All of us are artistic, we need that connection. … it makes it easier to transition between Common Core and what you are using in life. We’ve been going through normal Common Core stuff, I don’t see point in having that, but going over how it can be used in real life, we get a lot better.

Program Barriers and Challenges

Lack of time . Some pilot teachers were unable to finish all of the proposed units due to a variety of factors. Some teachers had to adjust pacing to scaffold lessons, others had to pre-teach concepts, while others suggest that due to the higher level of rigor, they had to take more time to review concepts so that students could successfully master the material. However, some of the teacher interviewees acknowledged the challenges associated with piloting new curriculum, with one person sharing their hope for next year, saying,

Now that I’ve been through the course one time, the flow of it should go a lot better next year. Now, with a better concept of how long activities will take, where I need to extend or take time, I think we can clean up the pacing a lot. Prep time is at a premium, it’s hard to take out time to make [lessons] perfect.

Identification of students. Students were identified for the pilot class through a variety of techniques ranging from open enrollment to teacher recommendations, to the review of previous math scores. This variance resulted in classes of students who ranged in skill and grade level. Some teachers suggested they struggled to differentiate in order to accommodate the wide range of skill levels. One teacher shared their experience, saying,

I don’t think we have all the right students in the class. Some are perfect candidates. Other times, it’s dealing with students who don’t want to be in any math class; for some of them, this is their 3 rd year math class and they need to be dialed in a little more than they are. If we are fortunate to get a better target population, I think that will help a lot. Sometimes differentiating creates choppiness. For a significant amount of time, I am fighting classroom discipline issues far more than I should have to. That has nothing to do with the curriculum, but everything to do with the people we put in the class.

School personnel, while discussing how this year had some challenges due to not having “the right fit” of students in the class, spoke positively about selecting seniors for the following year. One school representative discussed their strategy, saying,

T H E B E R C G R O U P 6

As we receive the SBAC scores, they will help us to determine who signs up for next year.

We will try to find students who are interested in going to community college and have a 2 on the SBAC. We will work with our college and career ready counselor and help to align those two.

Some focus group members discussed the newness of the SBAC assessment, with one person saying, “It will be interesting with the SBAC to see what a level two student looks like verse a level three student. I don’t think we’ll really know that for several years. … it will be interesting to see what happens.” The program will look different next year, as the course is intended for senior level students only. One teacher discussed the benefit of only working with senior students saying,

We will have seniors only next year, those that have a two on the SBAC. They’ll have a stronger foundation; will be ready for the higher level thinking it asks for. My current kids need more push before that. I think it’s why I was having trouble first semester. I realized they have to be seniors and need another year of math. It will be our prep for college type kids.

Lack of assessments.

Apparently, teachers piloting the program this year had to create their own assessments. While some teachers shared their assessments via the WAMAPS online portal, the process to create and post assessments can be “challenging” and time consuming. Interviewees discussed their wonderings around assessments and how they may impact the program next year.

As stated,

The program does not have any assessments. That is a weak part. We are going to have to put in assessments, and I’m asking if we should make them common. If we make it that everyone needs to get a B, then maybe we need to standardized the assessment- it’s a touchy subject. We’ve been left to our own assessments. Some [teachers] are doing more complicated, some are not. Next year, it has to be standardized if we are going to be giving the credits. This year, I have the freedom to assess at my level, but next year it will need to be standardized.

C ommon grading expectations . As mentioned above, program participants seem to be curious about grading expectations for next year, especially without the current provision of a common assessment. To further compound confusion, some schools use an A through F grading scale while other participating schools utilize a standards based system. One interviewee shared their concern about grading saying,

How do I know my B looks like your B? It’s hypocritical to say ‘you all have to grade the same’ when we don’t grade the same. It’s all based on trust. . . . If we say a B, how we get to that B will vary. A B level student in my class may not look the same as a B level student in another class.

Another teacher shared their concern, mentioning, “The hard thing is fidelity and how we’re going to ensure the checks and balances. Do we make sure everyone gives the same final? How do you

7 T H E B E R C G R O U P

ensure fidelity? There is just a huge level of trust that goes into it.” One person suggested site visits and “spot checks” might help to ensure new teachers, especially, are aligned with expectations.

Program leaders are working to address the grading and assessment concerns by identifying “what a

B grade looks like.” As stated,

We identified a B and not a B [level work],” shared one stakeholder, “That will be part of our training to say ‘this kid is a B, this one is not.’ If we take out ‘this is how you grade,’ and focus on ‘this is what your student should be able to do,’ it will be a huge piece.

Scheduling . While school personnel seem to recognize the value of the Bridge to College Math course, some are facing challenges with fitting the course into their master schedule. One person lamented,

It’s a very small group of kids that we will target. If a kid goes through pre-calculus and is successful, this is not the class for them. This is really for kids who took Algebra 2 level and struggles, who struggles taking tests. Now, we have a singleton class, how do we staff that and pay for it?

Associated program costs and technology challenges.

In the time of diminishing budgets, staff members are already thinking ahead as to how to sustain their efforts after the grant dissipates.

While the grant helps to provide money for materials and training, interviewees discussed concerns about the cost associated with the manuals and needed manipulatives. Other focus group members also discussed concerns associated with the level of technology needed to appropriately implement the program. As shared,

Some of it is consumables, some are not. They do offer an online version of the student manual, but it’s a PDF and kids can’t manipulate it. We do have it converted to Word to make our edits, but then you need infrastructure of technology to support it. We have computer carts, but with testing, could not use them for three weeks. It’s something we are already thinking about.

Another program participant shared their experience with the online model, saying,

My challenge is keeping up with the computer and trying to get things off the computer.

I’m not very versed in the computer. I’m still in cut and paste mode. I’m supposed to log in. We have changes that I need to access. I’m not as computer savvy as I should be. I’m able to download all the stuff, but sometimes it gets stuck downloading the videos. I download ahead of time and make sure it works. Our school blocks some things and I need to get help, it’s frustrating.

Evaluation Question #3: To what extent did the technical assistance support implementation?

Workshops, retreats, and trainings . Participating teachers piloting the program this year received a variety of support. Last summer, teachers gathered with program leaders during a

T H E B E R C G R O U P 8

retreat in Leavenworth to review the curriculum and to practice instructional strategies.

Participants met over the course of the school year in regional groups and will gather again in June to discuss course modifications and future plans. Interviewees seemed to appreciate the level of support offered, with one person describing the trainings as “invaluable.” As stated,

We learned [the lessons] first as teachers in training. The training was invaluable. We went through the same frustration as kids saying ‘this is not the way we were taught.’ We did the same projects, had to aim the (Gummy) bear, had the same fun in experiencing it.

Trainings also offered teachers the opportunity to collaborate with other project participants and leaders, helping to expand their knowledge about issues beyond the course. One teacher shared their experience, saying,

I’m teaching [the lessons], have been to all the workshops they have had since we jumped on board, learned about the curriculum, what goes on at the community college level, and why we are taking these actions. I like the group we work with because there are members from OSPI, so I understand Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and the Smarter

Balance (SBAC) better because of my work with this group.

Focus group members not only seem satisfied with the level of information provided, but indicated they are also learning from those who provide and attend the workshops. As mentioned,

All of the workshops we have been to, I haven’t missed any of them. After two days, I felt like I could use a week of it. Working with these people, the level of knowledge and expertise has been absolutely wonderful to work with.

One teacher suggested other teachers at their building would benefit from the provision of BTCM professional development, saying, “I would love some of our teachers to go to training and get excited about it. This is the most valuable training I’ve ever gone to. This is the best funded program.”

Online support . Teachers supported each other on a more regular basis through an online

WAMAP program. Through this format, teachers were able to share materials, supplemental lessons, assessments, and offer reflections and suggestions of ways lessons could be altered and improved. Although some teachers reportedly used this format more often than others, program participants overall seemed to appreciate the online community and the opportunity to connect with their peers. For those who did not use the portal as often, most interviewees claimed the posting process “takes a lot of time” or “is not something that is part of my nature.” As described by one program participant, “The online community is promising. The time that goes into that every day is challenging. It’s hard to post to the online forum. I do my own reflections at the end of day, but then to post adds another step.”

Support from Administrators, OSPI Personnel, and Program Leaders . When asked to describe the successful aspects of the support received, interviewees identified support from the district and school level administrators, from OSPI, and program leaders as crucial to their efforts. While the

9 T H E B E R C G R O U P

level of support varied from each of these entities, preliminary findings indicate piloting teachers felt supported in their attempts to implement the lessons with fidelity. “The level of support has been fantastic. They are trying to give us guidance and freedom. They want as much feedback as possible to make it run more smoothly. I only wish we had more time together,” shared on focus group member. Likewise, building administrators, while fluctuating in the level of program knowledge, seemed to support the efforts of their piloting teachers and of the program overall. As stated by one administrator,

The more options our kids have for math, to keep taking math, is good. Whether kids are going to do pre-Calculus, this is another option for them to keep building skills, especially for those who are not quite ready. It gives them the opportunity to build some skill.

Evaluation Question #4: What organizational changes are required for, or correlate with, successful project implementation?

Stakeholders identified a few organizational changes that may help the success of the program and help to create a smoother transition for new teachers who will pilot the program over the course of the grant. These changes are explored below.

Increase collaborations with colleges. Increased partnerships of high school staff with college personnel could help to create smoother transitions for graduating students, can aid in creating

“post-secondary” common language, and may help to build transparency around expectations and practices by both educational institutions. While this program is still in the beginning stages of implementation, high school and college professors are already reportedly starting to share their perceptions and to break down misconceptions about instruction and education. One teacher discussed how this experience has helped her, saying,

This is a great opportunity. This is the first time we really have colleges involved. My eyes were opened with working with Core to College that the standards vary and competencies vary from college to college; that there are different entrance exams and requirements. We don’t have a target then (as a high school); we have 50 targets to prepare our kids for. This

(course) is a more level playing field, we have a target now, a B or better and we know what that looks like.

One focus group member discussed the need to create a structure for ongoing collaborations at the

Kindergarten through 16 levels, saying,

If this is viable and worth it; the continued support, the dollars are needed. The support, the technology needs to be there. Looking ahead and projecting ahead three to ten years down the road, the Kindergarten through 16 model needs to come together with us. The

13-16 part needs to come down to meet with us.

Improve student recruiting process/communication.

When asked what organizational changes or policy changes are required for successful project implementation, one interviewee discussed the

T H E B E R C G R O U P 10

need for early communication and proactive recruiting so to appropriately target the “best fit” students. As shared,

The recruitment of kids is a communication issue. Finding out we were going to do this so late last year was the problem. We will have better, more appropriate groups of kids next year. It wasn’t easy to contact kids last year because they were gone for the summer. We didn’t know much about it or what we were targeting.

Other focus group members suggested it would be helpful to communicate with other math teachers earlier in the year to gain student recommendations and to increase communication about the course to potential students and their parents so to create a better understanding about course goals and expectations. Similarly, some teachers report that counselors did not understand the program, believing it was more of remedial math class, and subsequently enrolling juniors who had just completed geometry, but were not ready for algebra 2.

Furthermore, at a couple of schools, there was confusion on whether students planning to enroll in

Running Start could take BTCM early. School personnel saw this as a potential solution for students who can do Running Start full time, but are not yet ready for college level math.

Ensure schools have the “right fit” teacher for the course.

Teachers piloting the program have a collection of professional experience ranging from years of teaching to those newer to the field.

During discussions, teachers, students, and administrators alike discussed the importance of having a teacher who is open to teaching “out of the box.” Reportedly, because the curriculum includes lessons that are student centered, hands on, and project based, teachers may need to adjust their instructional style to successfully accommodate the teaching strategies needed for lesson implementation. While this method of instruction may come more naturally for some more than others, it may behoove administrators and program leaders to have a clear understanding of the type of instructional practices required by the curriculum so to properly identify a teacher to teach the course. One administrator supported this idea, saying,

You need the right personnel. You need a staff who is willing to teach growth mindset. We are hitting growth mindset hard. If we had a teacher who was not open to that, we’d be dead in the water. Training for that staff member is just as important.

Some teachers, who previously had not taught this way, suggested there should be some training and support to develop the instructional strategies. One teacher shared, “I have never taught this way, I’m traditional. However, I have the willingness to learn. Not every teacher would be willing to do this.”

Allow for common planning time for teachers . Teaching a new curriculum can be challenging and confusing for even veteran teachers. The opportunity to collaborate about lessons can be especially crucial during the adoption of a new course. In some cases, two teachers from the same school piloted the program and may or may not have had the same planning period. Teachers may benefit from the opportunity to plan together so to discuss lessons, to create common assessments,

1 1 T H E B E R C G R O U P

and to reflect and modify lesson plans. One teacher praised the opportunity to plan with another teacher piloting the program this year, saying,

We do have same planning time and we spend a lot of time talking. If you have multiple teachers (teaching BTCM), it would be really beneficial to make sure they have common planning and to have a TA (teacher’s assistant) to help make the kits. As a teacher, it is a huge time commitment.

In many cases, teachers were solo in piloting the program at their schools, but had neighboring districts or schools with other teachers implementing the program. In this instance, it may behoove teachers to have the opportunity to have release time to collaborate with neighboring teachers so to plan and reflect together. One teacher shared their wish for next year, saying, “If I had the same prep time as someone (in a different school), I could go over and see [observe] and coordinate, it would work well. We need to work up a system so that we are not left out in the cold.” This is a plan of support for next year.

Evaluation Question #5: To what extent do the initiatives impact student outcomes?

Stakeholders mentioned examples of ways students are impacted by the BTCM course. Increased attendance in BTCM classes, “more student engagement,” and lower disciplinary referrals are a few of the ways the initiative is positively impacting student outcomes. Other examples are explored below:

Increased student self-confidence.

When looking at the impact of student outcomes, one thing to consider is the way the course has impacted student learning and perceptions about themselves as mathematicians. During focus groups, students seemed excited to talk about their experience, boasting about improved grades and how they “finally understand math.” As stated by one student,

The best thing is that I just understand the material a lot better. It’s more familiar territory with me for stuff that I’m good at with math. I feel it boosts my confidence up with skills in math. Definitely, I felt my confidence in math rise a lot.

Teacher interviewees also indicated seeing a shift in student self-confidence when it comes to math and learning mathematical concepts. One instructor shared their experience, saying,

Some students have been really openly positive about it. I’ve had some kids say ‘I’ve never understood math before and now it makes sense. … I’ve had kids say they like that it’s a lot more application and that we do not assign a ton of homework. There is a lot of independent practice.

Adaptation to a new way of learning.

Another factor to consider when thinking about student outcomes is the fact that the BTCM course is not taught in a “traditional” way and differs from other high school math courses, causing students to adapt to a new way of learning. Students have been learning math taught in a certain manner over the course of their entire educational career.

While this shift might seem vulnerable, unfamiliar, or frustrating at first, most students seemed to

T H E B E R C G R O U P 12

have adapted to and embraced the BTCM way of instruction. When asked how the BTCM course differs from a more traditional math course, responses varied. One focus group member shared, “I think it’s a little more loosely formatted. Because of the flexibility and autonomy that comes with the program, you have the ability to just react to how your students are reacting to the material.”

The integration of hands on assignments paired with “less drilling” and the use of “effective real world contexts” are other contributing factors to student success. “The curriculum focuses on a deeper understanding but doesn’t have a lot of math drilling,” shared one teacher, “This is wonderful in that the students get a better understanding of what they are doing.” Although some students prefer “traditional” math courses to the BTCM course, students reportedly enjoy “how interactive” the lessons are. One teacher reflected on their student’s progress over the course of the year, pointing out the fact that students are covertly learning without them even knowing it. As stated, “I see students making connections that they might not see themselves. I see attributes they haven’t enjoyed about math courses, but I see them starting to put things together. … I think the class has been very effective in that regard.”

Increased life skills. A major component of the BTCM course is to help students to be eligible for college level math. Stakeholders suggest that students are not only learning math concepts but other skills necessary for college, career, and life. When asked if she believes students will be ready for college level work after successful completion of the course, one teacher responded in the affirmative, saying,

I think they are going to be more life ready, not just college ready. That is the path, some will be college and life ready. They are better thinkers and that’s what we want. Some said they are going to work with their dad, but they will still need to take a class, they are life ready.

Among many skills observed, teachers especially report seeing students collaborate more with their peers, helping to create a supportive learning environment much like a career situation where students can learn from each other. One instructor shared,

They go out of their groups to help each other. They don’t just sit and wait for the teacher.

They are much more helpful to each other and for each other. They don’t just go to the answer key anymore, but depend on each other. They check with each other for the right answer and are very confident about their answers.

Finally, one administrator discussed the merits of the course, linking the skills students learn in class to a successful future. As mentioned,

There is a true bridge being built from this (course) to college. It’s taught differently too.

It’s more Common Core, standards based. . . . It truly is getting kids to see what they are going to see with Common Core. When you hear about critical thinking, you see things in there that are not in traditional math. It’s more of a 21 st century learning approach with skills students need. Students will be more successful in the future because of what the process emphasizes, the hard work needed, and the growth mind set promoted.

Perseverance is being pushed. I’m trying to get other teachers to teach like this.

1 3 T H E B E R C G R O U P

STAR DATA RESULTS

WHAT IS THE STAR INSTRUCTIONAL FRAMEWORK?

The STAR Instructional Framework serves to help organize and operationally define effective classroom practices. STAR is an acronym that stands for Skills , Thinking , Application , and

Relationships . S kills are manifested as the teacher provides opportunities for students to develop rigorous conceptual understanding, not just recall. T hinking is evident as the teacher provides opportunities for students to respond to open-ended questions, to explain their thinking processes, and to reflect to create personal meaning. A pplication of skills, knowledge, and thinking is evident as the teacher provides opportunities for students to make relevant, meaningful personal connections and to extend their learning within and beyond the classroom. R elationships are positive as the teacher creates optimal conditions for learning, maintains high expectations, and provides social support and differentiation of instruction based on student needs. The STAR

Instructional Framework is the basis of the STAR Classroom Observation Protocol.

WHAT IS THE STAR CLASSROOM OBSERVATION PROTOCOL?

The STAR Classroom Observation Protocol ® (STAR Protocol) is the instrument used to measure the extent to which effective, cognitive-based, standards-based classroom practices are present in the classroom. One third of the Indicators (n=4) are designed to measure the extent to which the teacher initiates effective learning activities for students. Two thirds of the Indicators (n=8) are designed to measure the extent to which students are effectively engaged in their learning. The

STAR Classroom Observation Protocol is scored on all 12 Indicators, all 4 Essential Components, and Overall. The 4-point scoring scale represents the extent to which Powerful Teaching and

Learning is evident during an observation period. The Indicator and Component scales range from

1-Not Observable to 4-Clearly Observable. The Overall score represents the extent to which the overall teaching and learning practices observed were aligned with Powerful Teaching and

Learning. The 4-point scale ranges from 1-Not at All, 2-Very Little, 3-Somewhat, and 4-Very.

Figure 1 shows the extent to which classroom practices were aligned with Powerful Teaching and

Learning during the study, combining Somewhat and Very aligned .

Data was disaggregated to show the differences between the Bridge to College Math teachers and a corresponding Algebra II class in each of the schools visited. During the most recent data collection, 65% of the BTCM classrooms observed were aligned with Powerful Teaching and Learning. This is compared to 39% of Algebra

II classrooms. The STAR Average is 48%. Figures 2 to 5 show Essential Component level scores.

Figure 6 shows overall scores for each level of alignment: Not at All, Very Little, Somewhat, and Very .

Results by Indicator are provided in Table 1.

T H E B E R C G R O U P 14

Overall Results

How well was this lesson aligned with

Powerful Teaching and Learning?

Not at All/Very Little Somewhat/Very

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

39

62

65

35

48

52

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

Figure 1

Skills: Essential Component Results

Did students actively read, write, and/or communicate?

1=Not Observable 2 3 4=Clearly Observable

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

15

54

35

47

31

0

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

18

0

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

Figure 2

24

42

24

10

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

1 5 T H E B E R C G R O U P

Thinking: Essential Component Results

Did students demonstrate thinking through reflection or metacognition?

1=Not Observable 2 3 4=Clearly Observable

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

8

31

24

41

10

28

34

62

35

0

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

0

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

28

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

Figure 3

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Application: Essential Component Results

Do students extend their learning into relevant contexts?

1=Not Observable 2 3 4=Clearly Observable

0

8

46

46

41

47

12

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

9

19

26

46

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

Figure 4

T H E B E R C G R O U P 16

Relationships: Essential Component Results

Do interpersonal interactions reflect a supportive learning environment?

1=Not Observable 2 3 4=Clearly Observable

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

8

69

35

53

23

0

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

12

0

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

Figure 5

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

8

31

62

12

53

35

0

Algebra II

Spring 2015 (n=13)

0

Bridge to College Math

Spring 2015 (n=17)

Figure 6

Overall (scales 1-4)

How well was this lesson aligned with

Powerful Teaching and Learning?

Not at All Very Little Somewhat Very

26

55

16

3

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

12

36

38

15

STAR Average

(n=11,269)

1 7 T H E B E R C G R O U P

Researchers noted several specific areas of strength, along with potential areas for targeted improvement. Some Components such as Skills and Relationships are overall strengths for both sets of teachers while BTCM teachers scored higher in all categories. While comparing the BTCM indicators to the Algebra II teacher indicator results (see Table 1), it seems both subsets of teachers are strong in assuring the classroom is a positive and challenging academic environment (Indicator

10), but in only 35% of BTCM classrooms and 15% of Algebra II classrooms were students observed demonstrating reflective learning (Indicator 6). STAR findings show students in classrooms taught by BTCM involved teachers demonstrated they were making meaningful personal connections a higher rate (29% verse 0%, Indicator 9) than in classrooms taught by

Algebra II teachers. This finding is consistent with student interviews, as students suggested the materials helped them to think in more real world contexts. However, the results show that more opportunities for relevance can be incorporated.

When asked how their instructional methods may have changed due to participation in the program, some teachers suggested they had to shift their pedagogy to include more activity based instruction and have changed the way they encourage student discourse. “I’ve moved my desks around to increase student collaboration,” shared one teacher, “We had to get used to working in teams. I tell them it’s a life skill.” “I like that we are no longer just standing up there giving answers,” shared one instructor, “I wish I knew about it earlier.” A smaller subset of teachers indicated that their instructional methods had not changed, and they were using traditional methods, similar to their other classes.

T H E B E R C G R O U P 18

Table 1.

Disaggregated STAR Indicator Results of Bridge to College Math and Algebra II teachers

Skills Indicators

1. Teacher provides an opportunity for students to develop and/or demonstrate skills.

2. Students’ construct knowledge to develop conceptual understanding, not just recall.

BTCM

3 4

47% 41%

88%

35% 41%

76%

Algebra II

3 4

54% 15%

69%

54% 15%

69%

3. Students engage in communication that builds or demonstrates conceptual understanding.

Thinking Indicators

4. Teacher uses a variety of questioning strategies to develop critical thinking.

29%

3

35%

65%

65%

35%

4

29%

54%

3

38%

62%

54%

8%

4

15%

5. Students develop and/or demonstrate effective thinking processes.

35%

59%

24% 31%

38%

8%

6. Students demonstrate that they are reflecting on a prompt and/or on their own learning.

29%

35%

6% 8%

15%

8%

Application Indicators

7. Teacher assures that the purpose of the lesson is clear and relevant to all students.

3

41%

53%

4

12%

3

38%

38%

4

0%

8. Students demonstrate a meaningful personal connection to the lesson.

29%

29%

0% 0%

0%

0%

9. Students produce something for an audience within or beyond the classroom.

0%

0%

0% 0%

0%

0%

Relationships Indicators

10. Teacher assures the classroom is a positive and challenging academic environment.

3

59%

88%

4

29%

3

77%

92%

4

15%

11. Students work collaboratively to provide social, peer-support for learning.

24%

53%

29% 31%

38%

8%

12. Students experience learning activities that are adapted to meet the needs of diverse learners.

59%

65%

6% 23%

31%

8%

1 9 T H E B E R C G R O U P

Bridge to College English Language Arts

The Bridge to College English Language Arts (BTCELA) curriculum is still in its developmental stage, but is well on its way to becoming a succinct curriculum. Its group of developers, the

BRIDGE team, consists of college professors, high school teachers, and stakeholders from OSPI and the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges. They researched multiple sources, including programs from California State University, Shoreline Community College, the Southern Regional

Education Board, and Engage New York to create a curriculum that adheres to Common Core

State Standards, Washington State graduation requirements and college acceptance requirements.

One stakeholder explained, “Part of the reason of having multiple sources is [when] teaching

Language Arts on a college [campus], Language Arts means five different departments doing different things.” Another interviewee elaborated,

We didn’t necessarily look at the whole course as a unit, but we looked at the modules within. We looked at all the core components, and how we can allow for differentiation that meets the non-negotiables. We are trying to model building a curriculum by owning the way we know the colleges will employ it. We are trying to set up a system so teachers can do it with fidelity.

During this pilot year, the Bridge team continues to develop and adjust the modules as needed.

Although the BTCELA curriculum is meant to be taught as a full course, during this pilot year, teachers were asked to implement one module in existing English classes. Overall, teachers involved in implementing the modules approved, stating that their students seem to show improvement in perseverance, reading, writing, and college preparedness. Some challenges they faced during implementation were issues with pacing, working in isolation, a lack of rubrics, and a decrease in student motivation.

Next year, the BTCELA curriculum will be implemented as intended, as a fourth-year (senior) course, designed for students scoring a Level 2 on the spring Smarter Balanced high school (11th grade) assessment. However, during this pilot year, modules were taught in pre-existing 11 th and

12 th grade (mostly) classes, with students at mixed ability levels, ranging from special education to advanced placement. Because of this, some teachers indicated they have had a challenging time differentiating the modules for all skill levels. For upcoming years, teachers intend to implement the entire curriculum and most state they will be using SBAC scores to identify students eligible to take the course. Some voiced concern on whether or not they will receive SBAC scores in time for scheduling, as one teacher voiced, “The hardest part about [scheduling] this is our schedules are completed before we get [SBAC] test scores back. We’re going to have to go back and change schedules. There’s no way around that.” These issues are explored further below.

T H E B E R C G R O U P 20

Evaluation Question #1: To what extent was the initiative implement as intended?

English teachers piloting the program this school year faced some unique challenges while implementing the curriculum. While recognizing the importance of teaching the unit with fidelity, some teachers did adjust the modules based on their needs. Most teachers modified the modules by omitting questions or activities, adding essays and supplementing material, and adding rubrics or checklists. A common concern among most teachers was the length of time it took to teach an entire unit. One interviewee explained, “It took longer to implement than expected. I’m now finishing up week 8, and I thought it would take 5 weeks.” “I was rushed at the end, so I didn’t spend as much time teaching the writing as I should have,” shared another participant.

Other teachers discussed how they adjusted the modules to overcome obstacles. One participant explained, “I tried to send [the students] home to read but less than half did it. I had to change to doing book reading in class, so we couldn’t do discussion activities about the book, because we were just trying to get through the book.” Another teacher described, “I implemented a couple of documentaries that fit perfectly in with the curriculum. The kids liked that they had a story line and it kept them engaged.”

When asked how they would improve the program, interviewees suggested ways to reduce the amount of time spent on the module. Some participants suggested spending less time on each lesson or omitting redundant activities. Other teachers discussed the need for scaffolding. One teacher reflected,

I think we’re going to have to build in some scaffolding because there are going to be some kids who don’t have the skills. Some of the texts are already college-level texts. I think there is some work that still needs to be done; I think it’s too high right now.

Overall, program participants seem to understand this year was a pilot year and worked to address any challenges that arose.

Evaluation Question #2: What are some strengths and barriers/ challenges to implementing the initiative?

When asked to identify any strengths or challenges to implementing the BTCELA modules, participants identified many common themes.

Program Strengths

Based upon data collected, strengths of the BTCELA modules included: an improvement in student outcomes, the inclusion of applicable activities within the modules, the potential of the modules, and the partnership between high school staff and college professors. These improvements are described below.

Improved student outcomes. Teachers identified improvements in student outcomes, such as an increase in student willingness to persevere through challenging assignments, advances in students’

2 1 T H E B E R C G R O U P

reading and writing capabilities, and increased college readiness. One interviewee shared, “The writing pieces [have been a success]. I see the writing improving and it is connected to the reading.”

Other teachers identified seeing “an increase in critical thinking” and “better discussion questions” as other measures of improvement. These developments in student outcomes will later be explored further.

Applicable activities. Interview participants reportedly enjoyed the real-world connections and application within some of the modules. Activities such as debating, reading scholarly articles, and creating portfolios asked the students to apply their learning to the real-world. One interviewee described, “I loved the pre-reading activities that were suggested. I had never done a debate before

… they were fun and the students could relate to them.” Another participant noted a change in their students, stating, “The final essay is directly linked to the real world. The students ate it up.

Their writing and thinking was better. They seemed freer because they were talking about their lives.”

Potential of the modules. When asked whether or not their module should be included in the year long course, the majority of interview participants responded favorably. Although stakeholders did voice concerns on the length of time it took to implement the units, the majority of them reportedly believed that the overall concepts covered within them were important. When asked about his module, one teacher said, “I thought it was a really great module. I think there needs to be a few tweaks to it, but the learning skills that were included were solid.” Another shared, “Yes, I believe this module should be included because of how it builds the students’ critical thinking skills.”

Partnership between high school staff and college professors.

Some interview participants identified how the collaboration between high school staff and college professors was a strength of the BTCELA curriculum. “There is more validity to the work we are asking [students] to do as a result of developing [the curriculum] with college professors,” shared one participant. Another added, “I’ve partnered with college professors before and recognize the value of having input from professors.” Other stakeholders noted the importance of incorporating input from high school teachers throughout the development of the curriculum.

“ We are talking about high school courses taught by high school teachers. They understand that landscape more than I do. We need both groups to sign off on this,” shared one stakeholder.

Program Barriers and Challenges

Interviewees also identified four major challenges when implementing the BTCELA modules: issues with pacing, working in isolation, a lack of rubrics, and a lack of student motivation. These factors are further discussed below:

Issues with pacing. While implementing the modules, teachers noticed that in order to complete every activity and lesson, they would need more than the time they initially allotted to complete the unit. One interviewee explained, “We agreed we wanted to have fidelity to the module, but we realized if you really paced it out, it would take so much longer than we had available.” Other teachers noted that students lost interest in the unit due to its length and redundancy. “My kids

T H E B E R C G R O U P 22

struggled with the length [of the module]. A traditional unit takes maybe six weeks tops. This unit took me probably ten weeks. My kids were just done.” In order to complete the modules, some teachers modified the lessons. “When I first saw [the module], I thought there were a lot of different kinds of texts, so I thought I would use them all. That’s how I started. Then I realized halfway through there is no way. If I do all of them, it would have taken me another three weeks.” one teacher shared. “The time it took to get through everything was a struggle. It’s dense. I ended up going through [and deciding] what are the necessary lessons and what may be things that could be taken away,” explained another participant.

Working in isolation. Some teachers who found themselves to be the only one implementing a unit in their school, or sometimes in their district, noted they faced certain challenges working alone. Reportedly, some felt they would have benefited from having someone with whom to share concerns or ideas. “It would have been nice to have another teacher teaching the same module, so I could have a conversation about it,” shared one interviewee. “Had there been another person in the building teaching the module I could have gone and talked to them [about the unit]. We could have discussed how to make the discussions more interesting,” shared another participant.

Lack of rubrics and grading expectations. Some teachers discussed the challenge of not knowing what the expectations were for student work. One teacher shared, “I think there needs to be a standard rubric … we need to develop some anchor sets so we know across the state what an A looks like and what a B looks like.” Another expressed, “[We need] exemplars for teachers and students - what does a 4, 3, 2, 1 look like?” Stakeholders are aware of this shortfall and are working to amend it. As one stakeholder discussed,

That is still a work in progress. We need to build from some obvious sources, and we need to look at Smarter Balanced, and some rubrics. We aren’t starting from scratch, but we need to build common rubrics to assess that with fidelity.

Another stakeholder further explained,

For the English side, we have a need on the higher education side, that when we talk about student performance, they aren’t just written. There is a leap of faith in a logic model, that an A or B isn’t on a piece of paper, it is also the grit and habits of mind of students. We are looking at how we are collectively agreeing on the profile of the College Bound student, which a test and grade can’t quantify. It will inform what we are teaching the children on the way.”

Lack of student motivation. Many interviewees described the challenge of keeping students motivated to complete the unit. “There was some push-back from the students - passive aggressive behavior, like not participating in class, not answering questions, wanting to put their heads down to go to sleep, or not turning in assignments,” illustrated one participant. Another described,

The homework issue was a problem - if I said take this article home and read it, I knew the next day when we discussed it, at least 75% of my kids hadn’t read it. We had to do [the reading] in class and that took time.”

2 3 T H E B E R C G R O U P

Some interviewees theorized reasons for this behavior,

It’s a long unit. It took ten weeks to get through it. If you don’t have a kid that’s really dedicated to putting the time into it, they will get bored. Even if it’s engaging, they just won’t want to continue,” shared one teacher.

Another teacher suggested, “I don’t think the purpose for the unit was clear to [the students]. It wasn’t explained to them … I don’t think they understood that learning this information could help them make changes in policy or address issues in society.” Other interviewees suggested “senioritis” was the reason for the students’ lack of motivation. “Senioritis has kicked in, many [students] are emotionally and psychologically checked out,” explained one interviewee. Finally, teachers suggested that when students had a “carrot” or reason to take the course, such as entering college level English in their first year of college, there will likely be more motivation.

Evaluation Question #3: To what extent did the technical assistance support implementation?

At the school level, most teachers reported that administration was supportive but uninvolved. One interviewee explained,

“They were very supportive of me deviating from our original curriculum to administer it to our students … other than that, they just left me alone to do what I do. They were interested in it, but didn’t approach unless I initiated the conversation.

Another focus group member shared, “The school has been very supportive. They basically trust us to make the decision that if we think it’s good for our school and students we will do it and if not, we won’t.”

Overall, when asked how OSPI/SBCTC provided support to Bridge to College grantees, interviewees identified the initial training offered in January as the one opportunity they had to come together. One stakeholder explained, “[Teachers] participated in regional meetings … there wasn’t the full group thing, because they were just doing the one module.” Teachers described the training as “helpful” and “an opportunity to get contact information.” Although some teachers identified a Google folder and a webinar as opportunities to share ideas, reflections, and rubrics, others seemed unaware of these options or expressed a desire for more chances to share information. One interviewee disclosed, “I wish I would have had more webinars related to this specific unit. Maybe even contact information of someone else doing the unit to see what was working for them and what wasn’t.” Another explained, “You need a network of people you can immediately call or text…to bounce ideas off of. [You need] periodic meetings, webinars, wikispace where you can go in and peruse what other people have tried.”

With full implementation planned for next year, teachers will receive more training. According to the District Assurances, each district will “release participating teachers for 5 full days during the school year for course training/PLCs and support teacher participation in a 3-day summer training.” It also states districts will “provide support as needed for one or more college faculty to serve as local or regional collaborative partners with the high school teachers offering the course.”

T H E B E R C G R O U P 24

These commitments will serve as more opportunities for teachers to gain support throughout implementation in the upcoming year; however, it may behoove stakeholders to brainstorm ways teachers can communicate with each other outside of training.

Evaluation Question #4: What organizational changes are required for, or correlate with, successful project implementation?

Stakeholders identified a few organizational changes that may assist with successful project implementation. These changes are explored below.

Clarify the pacing.

Many interview participants expressed grievances over the pacing of the modules. Some lessons took days longer to teach than initially anticipated and some modules took weeks longer to finish. Factors that played into this included having to pre-teach concepts or vocabulary and having to add in mini-lessons to keep the students engaged. Though some interview participants acknowledged that the pacing might get better when students are closer to the same skill level and when the students are correctly places into the class. It may behoove stakeholders to provide a pacing guide and amend some of the lessons to reduce redundancy and time spent teaching them.

Allow for teacher autonomy. Given that teachers have the ability to take into account the myriad abilities and needs of students, many interviewees expressed a desire to modify the curriculum when it does not fit student needs. Some interviewees suggested having a “menu” of sorts where teachers have a list of “six activities per lesson and we can pick three that are best suited for our kids.” Another participant proposed allowing teachers to pick different modules. “Here are ten

[modules], pick five to teach,” illustrated the interviewee. Exploring how to allow for more teacher autonomy may build trust in the curriculum and demonstrate trust in the teachers to exercise professional judgement in determining what is best for their students. One teacher voiced his concern, “I am weary that teachers will not teach lessons to fidelity if they don’t have to freedom to make decisions about how some of the modules are implemented.”

Include formative assessments. Although teachers noted that modules included summative assessments, some teachers voiced a desire for all modules to include formative assessments that allow them to track changes in student performance throughout the year and from lesson to lesson.

Not only were they interested in tracking students’ academic performances, they wanted to see how the students’ character skills, such as “grit, perseverance, and self-advocacy,” changed over time. “I really hope [developers] find a way for students to self-assess themselves on these skills,” one stakeholder shared. Though some teachers took the initiative and created their own formative assessments, through reading journals and essay questions, doing so takes up more of their time and creates differences in assessment procedures across the board. Including formative assessments throughout each module in the BTCELA curriculum will help teachers monitor student achievement and growth and will create validity in measuring these outcomes.

Increase communication among stakeholders.

Because pilot English teachers have mostly been working in isolation from each other, it may be in the best interest of BTCELA stakeholders to increase opportunities for communication between all players involved in the program. Teaching a

2 5 T H E B E R C G R O U P

new curriculum can be overwhelming for any teacher. The more chances there are to work with others in the same position, the more supported and confident people feel. Although English teachers were typically the only ones piloting the BTCELA module at their schools this year, it may benefit teachers to have planning time to collaborate with teachers in neighboring districts or schools for the upcoming year. One teacher shared, “If we could get together and talk about things with teachers across the state that would be good too.”

Increasing opportunities for all high school staff involved in implementing the BTCELA curriculum to meet with college personnel would also be beneficial. One developer expressed, “My concerns about relationships came from the English side because English teachers have little exposure to this process, and they were brought into this in isolation.” Other interview participants expressed a request for “more communication between community colleges and high schools.” One interviewee shared her thoughts on the topic, “The partnerships with colleges I think is hugely beneficial, but I think there are changes needed for that. There’s just not enough open dialogue right now.” Creating more opportunities for communication could build a more trusting relationship between high school and college personnel and help increase buy-in and trust in the curriculum.

Evaluation Question #5: To what extent did the initiative impact student outcomes?

Interview participants mentioned multiple examples of how they perceived students were impacted by the BTCELA modules. They are discussed below:

Increased perseverance. Teachers identified an increase in student willingness to persevere through challenging assignments. As one teacher stated, “I’ve seen a willingness to take on a tough academic article and break it down to understand it; to find text based evidence that supports a point of view.” Another teacher shared, “I see them have more confidence in themselves in terms of tackling material that is difficult. They have strategies.”

Developments in writing.

Some teachers noted changes in students’ writing habits. “The kids are better at thinking about their audience when they write…they’re more aware of how to adjust their writing styles based on their audience,” shared one interviewee. Another shared, “I think kids will be much better prepared for the variety of writing that is expected in college.”

Progress in reading.

Other participants noted an increase in student reading comprehension. “The thing that was the biggest success and surprise was how well the students understood and worked with reading strategies,” shared one teacher. “It seemed [the students] became more aware of their reading abilities and processes,” stated another interviewee.

Better readiness for college.

Overall, teachers agreed that the modules would prepare students for college level work. “One of the strengths I see coming out of this unit is really increasing their

[students] inquiry in classroom discussion. I saw students asking more relevant and more probing questions as they went through the discussion.” Another teacher explained, “I think if all the units look like this unit, we will have a group of kids who are ready to hit the ground running. The quality of work is what I would expect to see at the college level.”

T H E B E R C G R O U P 26

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The BTCM and BTCLA courses are both in early implementation stages and in a state of revision and modifications. Over the course of the pilot year, participating teachers and staff have struggled with some challenges, have found ways to overcome barriers, and have seen some positive changes in student outcomes. Both courses will be implemented on a larger scale next school year and may require additional changes based on unforeseen outcomes. Stakeholders were able to identify some preliminary findings that have been summarized here. The conclusions below are a snapshot of the findings listed above.

Bridge to College Math Recommendations

Increase communication around expectations for participating teachers, college professors, administrators, students and parents.

Continue to modify and adjust the curriculum to accommodate pacing, missing concepts, and relatable real world experiences

Clarify expectations around student identification and recruiting for the course

Continue to work on a common grading and assessment system

Provide guidance for schools that may be struggling with course scheduling issues

Create a sustainability plan for schools to maintain efforts beyond the provision of grant money

Ensure schools have the needed technological infrastructure to support course needs

Continue trainings, workshops, retreats, and online sharing opportunities

Educate school administrators in how to hire “right fit” teachers and how to support teachers who implement the program

Strengthen partnerships with college and post-secondary staff members

Provide common planning time for teachers

Bridge to College English Language Arts Recommendations

Increase communication around expectations for participating teachers, college professors, and administrators

Continue to modify and adjust the curriculum to accommodate pacing and missing concepts

Communicate ways teachers can modify lessons and modules

Continue to work on a common grading and assessment system

Provide guidance for schools that may be struggling with course scheduling issues

Increase opportunities for trainings, workshops, retreats, and online sharing opportunities

Strengthen partnerships with college and post-secondary staff members

Provide collaboration time for teachers with other stakeholders

2 7 T H E B E R C G R O U P

The BERC Group, Inc.

22232 - 17 th Ave. SE Suite 305

Bothell, WA 98021

Phone: 425.486.3100

Web: www.bercgroup.com

T H E B E R C G R O U P 28