GAO THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

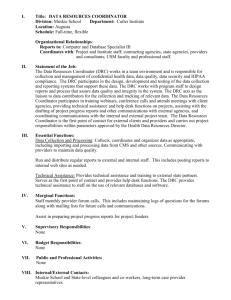

advertisement