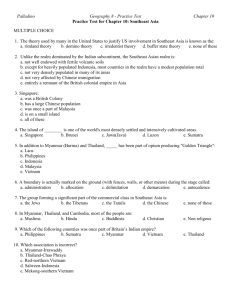

GAO SOUTHEAST ASIA Better Human Rights Reviews and Strategic

advertisement