GAO DEFENSE CONTRACT AUDITS Actions Needed to

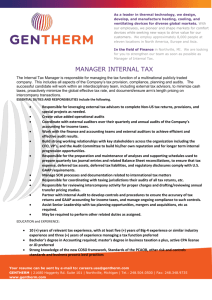

advertisement