CRS Report for Congress The Air Force KC-767 Lease Proposal:

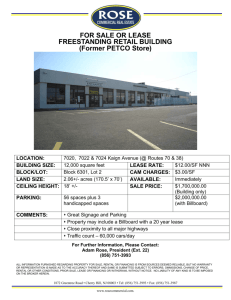

advertisement