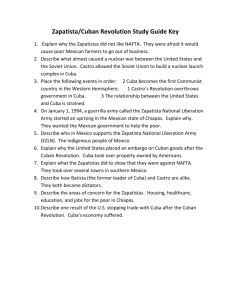

CRS Report for Congress Cuba: Issues for the 109 Congress

advertisement