Document 11052825

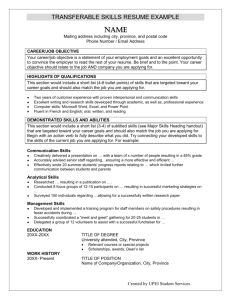

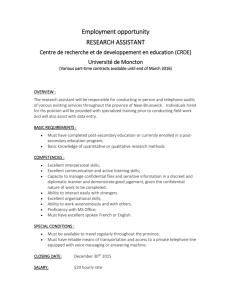

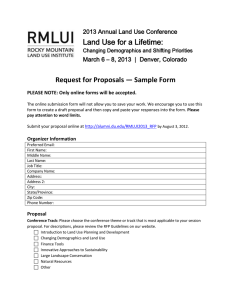

advertisement