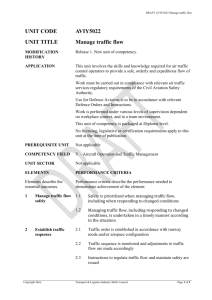

Airspace Control in the Combat Zone Air Force Doctrine Document 2-1.7

advertisement