THE CFE TREATY: A COLD WAR ANACHRONISM? Jeffrey D. McCausland

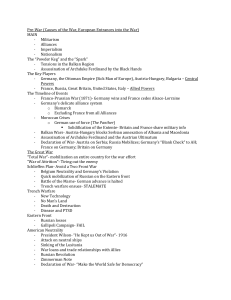

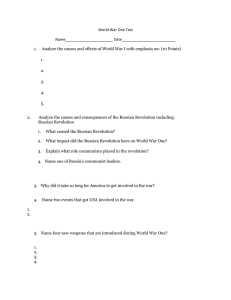

advertisement