GENERAL GEORGE C. MARSHALL: STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP AND

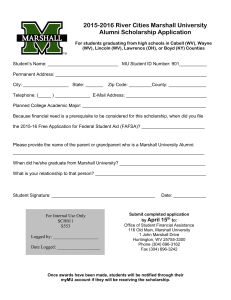

advertisement