A Practical Application of Concept Selection Methods ... III High-Speed Marine Vehicle Design HAGAN

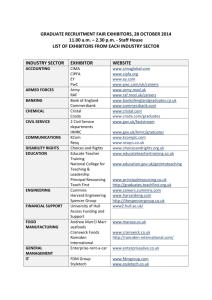

advertisement