Trash Media: How Competition Affects Information ∗ Julia Cag´ e

advertisement

Trash Media: How Competition Affects Information∗

Julia Cagé

Harvard University

November 18, 2012

Abstract

This paper questions the common wisdom whereby more competition in the media

industry leads necessarily to more information. I construct a voting model in which

individuals with heterogeneous tastes for “information” and “entertainment” vote strategically. I investigate the impact of a change in the intensity of competition in the media

market on the provided quantity of information and, through this channel, on electoral

turnout. I find that when newspaper buyers differ little in their taste for information and

the relative cost of producing information is high enough, more newspaper competition

leads to less information and a decrease in turnout. I confirm these predictions empirically

using a new panel of local daily newspapers and turnout at local elections in France from

1945 to 2011. I find that an increase in newspaper competition has a robust negative

impact on turnout at local elections. I next enter into the black-box of news-making to

explain this finding. I establish that, due to an important business stealing effect, an

increase in competition leads to a decrease in incumbent newspapers’ operating expenses,

and in particular the number of journalists. Through this channel, I find that an increase

in competition leads to (i) a lower provision of total news and, within these news, (ii) a

lower share of information and a higher share of entertainment. I finally show that more

competition leads to an increase in newspaper differentiation.

JEL No. D72, L82.

∗

I gratefully acknowledge the many helpful comments and suggestions from Alberto Alesina, Charles Angelucci, Daniel Cohen, Nathan Nunn, Dorothée Rouzet, Valeria Rueda, Andrei Shleifeir, Michael Sinkinson,

Nathalie Sonnac and James Snyder. This paper owes much to François Keslair who took an active part in

the construction of a first version of the dataset. I am also grateful to seminar participants at Harvard, the

Media Economics Workshop, MIT, NYU and PSE for input on this project. I would like to thanks all the

people and institutions that give me access to their data, especially the archivists of the French National

Archives. Cécile Alrivie, Danamona Andrianarimanana, Guillaume Claret, Georges Vivien Houngbonon, Romain Leblanc, Eleni Panagouli, Juliette Piketty, Graham Simpson, Kyle Solan and Alexander Souroufis provide

outstanding research assistance. This research was generously supported by the CEPREMAP, PSE and the

LEAP at Harvard. I also need to thanks the Center for European Studies for a Krupp Foundation Fellowship.

All errors remain my own. Email: cage@fas.harvard.edu.

1

”Half of the American people have never read a newspaper. Half never voted

for President. One hopes it is the same half.” (Gore Vidal)

1

Introduction

This paper questions the common wisdom whereby more competition in the media industry is necessarily leads to more information. More competition is often seen as implying an

increase in the dissemination of information, thereby enhancing the extent of ideological diversity. Indeed media competition, by raising the competitiveness of the marketplace of ideas,

is supposed to contribute to the political process. In this spirit, studies in political economy

have advanced that there exists a positive link between media competition and political participation. Be that as it may, there is however concern that the quality of the media might

have diminished during the last decades despite the manifest increase in the number of media

available. Indicative is the contemporaneous increase in the number of television channels

and the often perceived decrease in quality, exemplified by the multiplication of tabloid talk

shows and emergence of ”Reality” television.

In this paper I combine a voting model with a multidimensional differentiation competition

model to investigate the impact of a change in the intensity of competition in the media market

on the quantity of information provided and, through this channel, on political participation.

Information is defined as “accountability” or “fact-based” news, as opposed to entertainment,

defined as “commodity news” or “tabloid journalism”. On the supply side, profit-maximizing

newspapers choose the quantity of information and the quantity of entertainment they want

to produce, as well as their price. I first assume that there is only one newspaper in the

market (monopoly) and next study the impact of the introduction of a second newspaper

(competition). On the demand side, newspaper buyers differ in their tastes for information

and entertainment. They are also potential voters who behave strategically. The effect of

newspapers on voting is thus a by-product: voters information depends on the structure of

the news market and this information affects their participation. I find that when (i) the cost of

producing information is higher than the cost of producing entertainment and (ii) newspaper

buyers differ little in their taste for information, then newspaper competition leads to lower

information and, through this channel, lower political participation than monopoly.

I confirm these predictions empirically using a new panel of local daily newspapers and

turnout at local elections (city level) in France from 1945 to 2011. The choice of studying the

French news market is driven by the quality of the data I was able to collect.1 My dataset

1

The media literature relies mainly on American newspapers, with some exceptions: e.g. Di Tella and

Franceschelli (2009) on Argentina; Durante and Knight (2009) on Italy; Della Vigna, Enikolopov, Mironova,

Petrova, and Zhuravskaya (2010) on Serbia and Croatia; Enikolopov, Petrova, and Zhuravskaya (2011) on

Russia. To the extent of my knowledge, this paper is the first to construct a panel dataset on French media.

2

includes every local daily newspaper published in France over this time period. I observe

papers’ location, circulation, readership as well as, importantly, number of employees, cost

and revenue.2 I supplement this data with different measures of newspaper content described

in more details below.

Following Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2011b), my basic strategy is to look at

changes in political participation in cities that experience a newspaper entry or exit relative

to other cities in the same region and year that do not. I find that newspaper competition

has a robust negative effect on turnout. One additional newspaper decreases local turnout

by approximately minus 0.4 percentage points. When considering only newspaper entries, I

find that the effect of an entrant on the market is minus 1.1 percentage points. This effect is

robust to a range of alternative specifications and controls. Moreover using the timing of the

change in the newspaper markets, I undertake a falsification test which assesses the validity of

my results: I find no impact of a future change in newspaper competition on current turnout.

This suggests that changes in the number of newspapers are not driven by election results

and brings confidence in interpreting my effects as being causal.

I next enter into the black-box of news-making to explain this finding. I first establish

that there is an important “business-stealing effect”: the entry of a newspaper reduces the

circulation of incumbent newspapers by 25%. Due to this business-stealing effect, the entry of

a newspaper leads to a decrease in both the revenues and operating expenses of incumbents.

In particular, the entry of a newspaper leads to a decrease in the number of journalists working

for incumbents. Moreover, there is no overall increase at the news market level: the aggregate

number of journalists working in a county (a news market) does not increase with the number

of newspapers in this county.3 I finally show that, through this “journalist” channel, more

competition leads to (i) a lower provision of total news and, within these news, (ii) a lower

share of information and a higher share of entertainment. That is, if the same number of

journalists is divided into two newspapers, and each try to cover all the news, then they both

tend to produce lower quality news. This is a simple but powerfull mechanism that help

understanding how competition can hurt news-making.

The quantity of total news produced is measured using different indicators: (i) the number

of words by front page articles, (ii) the total number of articles by newspaper issue and (iii)

the total number of words by newspaper issue. I find that a one-standard deviation increase

in the total number of employees working for a newspaper increases the number of articles

2

To give a flavour of what is generally available in terms of newspaper cost and revenue data, it is worth

remembering that in their study of how economic incentives shape ideological diversity in the media, Gentzkow,

Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2011a) have no other choice but to use balance sheet data on 94 anonymous newspapers

that they match with newspapers using circulation value. On the contrary, I have annual balance sheet data

for 49 newspapers from 1984 to 2009.

3

By a small abuse of language and for the sake of clarity, I use in this article the term “counties” when

refering to French “departments”. Similarly, I use the term “states” when refering to “regions”. French local

jurisdiction are described in more details in the Appendix (Appendix Table 9).

3

per newspaper issue by nearly 0.7 standard deviation.

Within these news, I then study the distribution of articles across topics, separating articles on information (e.g. on economics or politics) and articles on entertainment (e.g. on

sports or leasure activities). I find that an increase in competition leads to a decrease in

the share of articles on information (and, symmetrically, an increase in the share of articles

on entertainment). I also find that a one-standard deviation increase in the total number

of employees working for a newspaper increases the share of articles on information by 0.3

standard deviation.

I finally show that more competition leads to more newspaper differentiation: an increase

by one in the number of newspapers in the news market leads to a 0.4 standard deviation

increase in the Herfindahl index of newspaper specialization.

Taken together, these results are consistent with the predictions of my model in which

(i) newspapers affect the political process primarily by providing information about elections

and (ii) this provision can be affected by change in the degree of competitiveness of the news

market.

Related Literature

There is a large political economy literature on how media affects

political participation, but its focus is much more on media access than on media competition.

Stromberg (2004b) finds that the introduction of the radio in the 1920s and the following rapid

increase in the share of households with radios led to more people voting in gubernatorial

races. Similarly, Oberholzer-Gee and Waldfogel (2009) find that the introduction of Spanishlanguage local television increases the turnout among Hispanics. Gentzkow, Shapiro, and

Sinkinson (2011b), using a panel of local US daily newspapers, show that one additional

newspaper increases turnout at national election but underline that the effect is ”driven mainly

by the first newspaper in a market”.4 My paper studies both theoretically and empirically the

non-monotonicity of this finding. Media access (going from 0 to 1 newspaper) can have very

different effects that changes in media competition (going from 1 to 2 newspapers, or from 2

to 3 newspapers). Given the dataset I am using, I am unable to capture the effect of the 0 to

1 margin (I always have at least one newspaper in a given news market). I am thus not able

to measure the effect of the first entrant but only the effect of later entrants. I find that this

effect is negative. This is consistent with the idea that an increase in the competitiveness of

the market may lead to a “race to the bottom” (Arnold, 2002).

The impact of competition on the revelation of information has also been the object of

a growing theoretical literature. Gentzkow and Kamenica (2012), assuming that information

is costless, find that competition among persuaders increases the extent of the information

4

See also Gentzkow (2006),Schulhofer-Wohl and Garrido (2009), Banerjee, Kumar, Pande, and Su (2010)

and Snyder and Stromberg (2010).

4

revealed.5 My framework is totally different from their – and much simpler – but it is worth

underlying that, once I assume that information is costly to produce, I obtain that more

competition decreases the provision of information.

A large theoretical literature also studies how media competition affects media ideological

bias. Mullainathan and Shleifer (2005) find for example that competition does not reduce and

might even exaggerate this bias (see also Besley and Prat (2006), Gentzkow and Shapiro (2006)

and Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2011a)). But as underlined by Prat and Stromberg

(2011) in their recent survey of the literature on the influence of mass media, this literature

“leaves out an important body of research in industrial organization (...) that deals with the

media industry, mostly without any direct reference to the political system”. In this paper

I try to fill this gap by combining two classical building blocks: a political economy voting

system to study political participation and a multidimensional differentiation competition

model to determine newspapers provision of information. From this point of view, my paper

is closely related to Stromberg (2004a) who combines a model of mass media competition

with a model of political competition. However the model of media competition I develop is

quite different from his model. While Stromberg (2004a) constructs a horizontal competition

model – his focus is on the location of each newspaper in the news space –, my model is a

vertical competition model with multidimensional newspapers which vary in their price, the

amount of information and the amount of entertainment they provide. This allows me to

obtain new predictions on how newspapers competition may affect information.

From this point of view my paper contributes to the industrial organization literature

on how concentration affects differentiation and variety and in particular the literature on

mergers. Using data on reporter assignments from 1993 to 1999 George (2007) shows that

differentiation and variety increase with concentration in markets for daily newspapers. Berry

and Waldfogel (2001), using evidence from radio broadcasting, find similarly that increased

concentration increases variety absolutely.6 Focusing on the impact of market size on product

quality, Berry and Waldfogel (2010) show that in daily newspapers, the average quality of

products increases with market size, but the market does not offer much additional variety as

it grows large. They measure quality with the size (number of pages) of the paper and the

number of reporters on staff which are also my variables of interest. Interestingly their finding

is driven by the fact that the cost of quality is fixed with respect to output, which is an important assumption of my model. Even more closely related to my paper, Fan (2011) develops a

structural model of newspaper markets to analyze the effects of ownership consolidation and

simulates the effect of a merger in the Minneapolis newspaper market.

5

On the contrary, Angelucci (2012) shows that an increased misalignment of preferences amongst persuaders

may lead to less information revelation and more imprecise decisions if information acquisition is costly.

6

Other examples in this literature include Della Vigna and Kennedy (2011) who study media concentration

and bias coverage using movie reviews, and George and Oberholzer-Gee (2011) who examine the impact of the

local market structure on viewpoint diversity in the market for local television news.

5

My study differs from this past work in the large number of media outlets and the long

period of time it covers and from the links it establishes between the impact of competition

on the quality of information and political participation. To the extent of my knowledge, it

is the first large-scale empirical study to relate changes over time in news market structure

to changes in the cost and revenue structure of newspapers and to link these changes with

changes in political participation.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that there is a growing empirical literature studying newspaper content but that the focus of this literature is on political bias and not on the quality

or quantity of information. Various measures of media bias have been used, in particular

measures of newspapers’ political leanings (endorsement, candidate mentions,...) using automated searches of news text. Groseclose and Milyo (2005) proxy the political positions of US

media outlets by the average ideology of the think tanks they quote. Gentzkow and Shapiro

(2010), exploiting the Congressional Record, use similarities between language used by media

outlets and congressmen. In this paper, I try to draw a new distinction between the share of

articles on information and the share of articles on entertainment newspapers produce.

Let me underline that, contrary to the existing literature, I assume in this paper that

there is no bias. I voluntarily choose to abstract from political bias considerations for two

reasons. First and most importantly, there is no political bias in French local daily newspaper

during my period of interest. As noted by Éveno and Des travaux historiques et scientifiques

(2003), since 1947, “the story of biased newspapers has been the one of a slow decline”. The

last local daily biased newspapers disappeared in France in the 1950’s. Second, it allows me

to keep the model tractable while identifying a new effect of newspaper competition on the

provision of information.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 below lays out the model

and investigates the impact of competition on the provision of information and on political

participation. Section 3 describes the novel panel dataset of French local daily newspapers and

turnout at local elections used in the study. Section 4 lays out my empirical strategy, discusses

identification and presents my main results as to the impact of newspaper competition on

turnout at local elections. In section 5 I open the black-box of news-making to understand

why more newspaper competition leads to less information. Section 6 concludes.

2

The Model

My model combines two blocks together: a voting model and a differentiation competition

model. The voting part of the model is closely related to Feddersen and Pesendorfer (1996)

and Feddersen and Sandroni (2006a,b). Society much choose between two alternatives by

majority voting. There are two states of nature: one in which all voters prefer the first can6

didate and a second state where all prefer the other candidate. Voters have state dependent

preferences: there are no partisans. I voluntarily chose to abstract from political bias considerations. Readers do not have political opinions and individuals are only heterogenous in

their preferences for information and entertainment. Similarly, there is no media bias and

newspapers are pure profit-maximizers. Agents are motivated to vote out of a sense of ethical

obligation. Each agent has an action she should take and receives utility from taking this

action. Hence each agent behaves strategically even though pivotal probabilities play no role.

This is described in more details below.

2.1

2.1.1

Model Set-Up

Nature

There are two equally likely states of Nature Θ ∈ {0, 1} that are unobservable. There is

a continuum N of agents who share common prior about the state of Nature (one half).

There are two candidates running for the election, candidate 0 and candidate 1: Ω = {0, 1}.

The candidate that receives the majority of the votes cast is elected (if there is a tie, each

candidate is chosen with equal probability). One can think of the two candidates as being

the “status quo” and the “alternative”, and assume that there is some uncertainty about the

cost of implementing the alternative which can be either high or low.

2.1.2

Agents

Agents take two actions. First they choose whether to buy a newspaper and next they choose

whether to vote.

Newspapers Differentiation

Agents first choose whether to buy a newspaper: α ∈ A =

{B, N B} (B: buy; N B: do not buy). I assume that there is unit-demand: agents cannot

buy more than one unit of the newspaper. Moreover I assume that there is no multi-homing:

when there are two newspapers, agents can only buy one of the two. They cannot buy both

newspapers at the same time. This assumption is made to keep the model tractable and

allows me to rule out a potential channel through which newspaper competition could have

negatively affected the information received by the buyers, namely “confusion”. Indeed, under

certain conditions, too much information can decrease the quality of the information – the

signal – received by the readers.

Agent i maximizes the following utility function:

bi xj − pj ,

Vi =

0,

if she buys newspaper j

otherwise

7

(1)

where xj is the ratio of information over entertainment included in newspaper j and bi is

agent i’s taste for this ratio. I assume that this taste is uniformly distributed over the interval

b, b : U ∼ b, b . pj is the price of newspaper j. Agent i buys newspaper j iff bi xj − pj ≥ 0

and (if there is competition) bi xj − pj ≥ bi xk − pk , ∀ j 6= k.

Newspapers maximize their profits by choosing their price p and the ratio of information

over entertainment x they want to produce:

"

max

(xj ,pj )

cx2j

pj Dj (xj , pj ) −

2

#

(2)

where Dj (xj , pj ) is the demand for newspaper j given xj and pj , and c is the production

cost of x. Under duopoly, newspapers simultaneously choose x and then compete on price p.

Intuitively, one can think of x as the fraction of pages in the newspaper devoted to information

that is costly to produce.

I assume that the news market is one-sided, i.e. I do not take into account newspaper

dependency on ad revenues. I recognize that newspapers derive revenue from both readers and

advertisers. Implicitly here I am considering advertising revenue as a per-reader proportional

subsidy.7

Political Participation Agents next choose whether to vote: s ∈ S = {a, 0, 1}, where a

denotes abstention, 0 denotes vote for candidate 0 and 1 vote for candidate 1. As I underline

above, there is no partisans. Voters have state dependent preferences, i.e. given a pair (ω, θ),

ω ∈ Ω and θ ∈ Θ, the utility of a potential voter is:

0,

if ω 6= θ

U (ω, θ) =

U > 0, if ω = θ

Moreover, I assume that there is a uniformly distributed cost to vote C ∼ U 0, C .

Every voter receives a message m ∈ M = {0, 1, φ}. Voters who receive a message 0 or

1 are informed and all others are uninformed. I assume that the information acquisition is

exogenous in the voting stage of the game: voters who buy a newspaper are informed and all

others are uninformed. In other words in my setting, the effect of newspapers on voting is a

by-product.8

I call q ∈ (0, 1) the fraction of informed voters in the population. q =

D

N

where D is

the demand for the newspaper in the monopoly case, and the sum of the demands for both

7

In Angelucci, Cagé, and De Nijs (2012), we introduce the two-sidedness dimension of the news market to

investigate how newspapers change their price discrimination strategies between subscribers and other readers

as a function of their dependency to advertising revenues.

8

A possible extension will be to endogenize the acquisition of information. However it will make the model

much less tractable without modifying its main predictions.

8

newspapers in the duopoly case (remember that N stands for the size of the population).

Among the informed voters, the fraction which observes the message m ∈ {0, 1} in state m is

ρ ∈ (.5, 1]. When ρ is close to 0.5 the message is a very noisy signal of the true state, while

when ρ is close to 1 the message almost perfectly conveys the true state.

I assume that ρ is an increasing function of x s.t. ρ (0) = 0.5 and ρ0 (x) > 0. In other

words, the higher the ratio of information over entertainment provided by the newspaper, the

better the quality of the signal received by the reader.

2.1.3

Timing of the Game

The game proceeds as follows:

1. Nature draws θ ∈ Θ = {0, 1}.

2. Newspapers choose the ratio of information over entertainment x and the price p.

3. Voters choose α ∈ A = {B, N B} (whether to buy a newspaper, and which one).

4. Voters choose s ∈ {a, 0, 1} (voting decision).

5. The state of nature is revealed.

I solve the game by backward induction.

2.2

Solving the Model

Solutions fall under three cases, depending on the degree of differentiation of consumers taste

for the information over entertainment ratio. Solving the game by backward induction and

comparing what happens to the information over entertainment ratio under monopoly (x∗m )

with what happens under duopoly (x∗d,1 ,x∗d,2 ), I obtain the following proposition.

Proposition 1

If b > 4b (high taste differentiation), then x∗d,1 < x∗m < x∗d,2 .

If 2b < b ≤ 4b (intermediate taste differentiation), then x∗d,1 < x∗d,2 < x∗m .

If b ≤ 2b (low taste differentiation), then x∗d,1 = x∗d,2 =

x∗m

2

< x∗m .

Proof. See Appendix.

The impact of competition on information provision thus depends on the degree of taste

differentiation. Proposition 2 tells us how it impacts turnout.

9

Proposition 2 (Rational Abstention)

(i) Only informed voters (reading a newspaper) vote. Uninformed voters never vote.

(ii) Among informed voters, if there are different degrees of information – two newspapers

with different x competing on the market –, then only the informed voters reading the newspaper with the higher x vote.

(iii) There is cut-off point such that better informed voters with voting costs above this threshold should abstain. This cut-off point is increasing in x.

Proof. See Appendix.

Combining Propositions 1 and 2 I obtain the following predictions from the model.

Prediction 1 (High Differentiation) If there is high differentiation in voters taste for information, then:

(i) Turnout is higher under duopoly than under monopoly.

(ii) Voters are better informed under duopoly than under monopoly.

Prediction 2 (Intermediate and Low Differentiation) If there is intermediate or low

differentiation in voters taste for information, then:

(i) Turnout is lower under duopoly than under monopoly.

(ii) Voters are less informed under duopoly than under monopoly.

In the following sections, I test these predictions empirically.

Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics9

3

3.1

3.1.1

Newspapers Data

Number of Newspapers

To determine for each year between 1945 and 2011 the number of newspapers present in each

French county I use various sources of information that I digitize and merge together. This

dataset is the first dataset on the long-run evolution of the French news market. I choose the

county as my unit of analysis since it is the natural news market.

I count local daily newspapers from these sources: in each year, I extract the name and the

county(ies) in which circulates every local daily newspaper. I match newspapers across year

on the basis of their title and county(ies), allowing newspapers to circulate across counties.

For each county-year, I then compute the number of local daily newspapers which serves as

my key explanatory variable.

9

For the description and the sources of the data in more details see the Data Appendix.

10

The sample includes 288 newspapers. I observe a total of 266 county-years with net

newspaper entry and 340 county-years with net newspaper exit between 1945 and 2011. These

266 entries and 340 exits are key for my identification strategy.

Newspaper Owners A possible concern might come from the fact that the effect of an

increase in competition may be different whether the entrant newspaper is owned by the same

owner than the incumbent newspaper, or by a different owner. To determine the identity of

newspaper owners, I use several historical sources described in details in the Data Appendix.

My sample includes 278 owners. Over the period, I observe a total of 281 county-years with

net owner entry and 387 county-years with net owner exit.

3.1.2

Newspaper Circulation

For the period 1945-1990, newspaper circulation data comes mainly from archival data that

I digitize and merge together. Data for recent years (1990-2011) comes from the OJD (the

French press observatory whose aim is to certify the circulation data).

Between 1964 and 2011, I also have data on the geographical dispersion of circulation

when newspapers circulate across nearby counties. Having this data is important since even

if local daily newspapers in France are county-level newspapers, some of them circulate across

counties. Hence I do not want to bias the analysis by constraining the news market to be a

county and newspapers to circulate only in the news market where they are headquartered.

Doing so would have lead to an underestimation of newspaper competition.

3.1.3

Newspaper Readership

I collect annual data on newspaper readership by newspaper between 1957 and 2011 from

studies on French newspaper readers conducted principally in order to provide information to

advertisers. For the 1957-1992 period, I digitize data from surveys conducted by the CESP,

a French interprofessionnal association gathering the whole of the actors of the advertising

market concerned with the study of media audience. For more recent years I download all

the annual audience studies available in an electronic format at the French local daily press

syndicate which accepted to share this non-publicly available information with me. These

surveys mainly cover for each newspaper information on its aggregate readership. However,

for the sub-period 1996-2004 there is also information on readership by county for newspapers

circulating across nearby counties. Having information on both newspaper circulation and

readership allows me to compute the ratio of reported readership to circulation.

11

3.1.4

Newspaper Profitability and the Number of Journalists

Firm Data (1984-2009)

I compute annually for local daily newspapers between 1984 and

2009 a number of important economic indicators, namely sales, profits, value-added, operating

expenses (payroll, inputs, taxes), operating revenues (revenues from sales and revenues from

advertising), and the number of employees. The panel data covers 43 newspapers from 1984 to

2009, plus 5 other newspapers from 1993 to 2009. This data is from the (i) Enterprise Survey

of the French national institute for statistics which covers the period 1993-2009, and the files

constructed for the tax regime ”Bénéfice Réel Normal” (BRN) by the ”Direction Générale des

Impôts” (DGI) from 1984 to 2009. I identify newspapers in the dataset by using the French

registry of establishments and enterprises.This dataset is, to the extent of my knowledge, the

most complete existing dataset on newspapers cost and revenue.

Journalist Data One of the important downside of using French data is that, contrary

to what exists for example in the United States, there is no media directory available with

information on the number of journalists by newspapers. Hence I have to find other data

sources in order to be able to estimate how competition impacts the number of journalists.

I use two different sources: (i) information on the total number of employees working for

each newspaper that is provided in the firm survey described above; (ii) for more recent

years (1999-2011), I obtain data on the number of journalists (and on the total number of

employees) directly from the local daily press syndicate.This dataset is not complete (it has

information for only 24 newspapers – I complete it by data I obtain directly from newspapers

when available) but it allows me to compute the share of the journalists in the total number

of employees. This share is pretty stable during the 13 years for which I have data (37% on

average) (see Appendix Table 11). The correlation coefficient between the total number of

employees and the number of journalists is equal to 0.94 (and statistically significant at 1%).

3.1.5

Newspaper Content

I use various sources to study newspaper content. First, I use newspaper front pages and,

for each newspaper issue, count the number of words by front page. There are a number

of advantages of using front pages. First, front pages are available daily for 51 newspapers

over the period 2006-2012. I download them from the local daily press syndicate using an

automated script. Hence the panel data of front pages is very complete and it is balanced.

Second, as shown below, there is a strong correlation between the number of words on the

front page and the total number of words and articles inside the newspaper. Using front pages

is not new in the literature. To establish evidence of media capture, Di Tella and Franceschelli

(2009) construct an index of how much first-page coverage of the four major newspapers in

Argentina is devoted to corruption scandals.

12

Second, I obtain the entire daily content of each newspaper issue by using an automated

script to retrieve for each day and each newspaper issue all the articles published in the issue.

I obtain this information by downloading the information available on two different websites,

Factiva and Lexis-Nexis, which aggregate content from newspapers. I construct a dataset

covering 22 different newspapers over the period 2005-2012. I use this information to obtain

measures of the quantity of the total news produced: the total number of articles and the

total number of words per issue. Berry and Waldfogel (2010) also use the size of the paper

to measure quality, but they measure it with the number of pages, not with the number of

articles per issue.

I next use the metadata associated with each article on Lexis-Nexis (title, subject, topic)

to classify articles between “information” and “entertainment”. The share of articles on

“information” is defined as the number of articles on agriculture, economics, education, environnement, international or politics, divided by the total number of articles that I am able

to classify. The share of articles on“entertainment” is defined as the number of articles on

movies, culture, leisure activities, sports, “news in brief”, religion or health, divided by the

total number of articles that I am able to classify. (By construction, the sum of both shares

is equal to 100).

Finally, I use the article classification in sub-categories to construct a measure of newspaper differentiation. This measure is simply an Herfindhal index varying between 0 – no

specialization, i.e. no differentiation between newspapers that all deal with all the topics

– and 1 – perfect newspaper specialization, i.e. important newspaper differentiation, each

newspaper being specialized in a given topic (e.g. music or sport). This index is equal to

the sum of the squares of the shares of the different newpaper topics in each newspaper issue: agriculture, culture, economics, education, environnement, health, international, leisure

activities, movies, “news in brief”, politics religion and sports. I compute it both on a daily

(considering each newspaper issue separately) and or a weekly basing (summing all the issues

of each newspaper for each given week together).

3.2

Electoral Data

The main focus of this paper is on mayoral elections (city-level elections). Studying the impact

of local newspapers on participation at local (rather than national) election is an important

difference with Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2011b) who study turnout at presidential

and congressional elections. However, since I am considering the impact of local newspapers,

I think that it is more appropriate to use local elections.

As of today, there are 36,570 communes in metropolitan France. I focus on the provinces

and do not take into account the “Paris area”.10 . There are 2,282 communes with more

10

In this area local daily newspapers are competing in a different way with national newspapers. Paris having

13

than 3,500 inhabitants in the provinces. In this paper I focus on these communes over 3,500

inhabitants since there is a change in the electoral rule for mayor elections for communes

under 3,500 inhabitants. For each election, I measure turnout as the ratio of cast votes to

eligible voters. I use cast votes rather than total votes since in France white votes are not

included in turnout.

Mayoral elections take place in France every six years. Between 1945 and 2010, 12 elections

took place (1945, 1947, 1953, 1959, 1965, 1971, 1977, 1983, 1989, 1995, 2001 and 2008). I

choose not to include in the dataset the turnout results for 1945 since this election took place

before the end of the Second World War in very special conditions and it happened just two

years before the 1947 election. Before 1983, data on French municipal elections have never

been digitized. Hence I construct the first electronically available dataset on French local

elections results at the commune level between 1945 and 1982, mainly from archival data.

More recent data are from the Centre de Données Socio-Politiques (CDSP) of Science-Po

Paris, the Interior Ministry, and Bach (2011).

3.3

Demographic Controls

City-level demographic data from the French census are in electronic format from 1962 to 2010.

I digitize data for the 1936, 1946 an 1954 censuses from books published by the INSEE. I

compute the share of the population that is 20 and older, the share of the population employed

in manufacturing and the share of the population having the baccalaureate or more. For each

measure, I interpolate both the numerator and denominator between census years using a

natural cubic spline (Herriot and Reinsch, 1973) and divide the two to obtain an estimate of

the relevant share.

4

Newspaper Competition and Electoral Turnout: Empirical

Evidence

4.1

Specification and Identification Strategy

I match my panel data on newspaper competition with mayoral election results from 1947 to

2008 and track the impact of a change in competition on turnout. Let C index cities, c index

counties and t ∈ {1, ..., 11} index election years (one time unit representing six calendar years).

The outcome of interest, yCt , is voter turnout. The key independent variable of interest is

NCt , which is defined as the number of newspapers in city C at time t.

I assume that

a national dimension, a lot of “local” information concerning the ”Paris area” is in fact taken into account in

national newspapers. Then there is much more competition between the different newspapers than in the rest

of France and considering only the competition between the local newspapers would be misleading.

14

yCt = αNCt + δxCt + ρC + µst + εCt

(3)

where ρC is a city fixed effect, µst is an election-state fixed effect, xCt is a vector of

observable characteristics, δ is a vector of parameters and εCt is a city-year shock. The

parameter α is the causal effect of NCt (the number of newspapers) on yCt . Since turnout

varies at the city level while the number of newspapers varies at the county level (if two cities

are in the same county, they have the same number of newspapers) I cluster the standard

errors at the county level.11

My identification relies on changes in the number of newspapers over time. As a result

it is correct as long as the timing of these change is random. I undertake a falsification test

using the timing of the change which seems to confirm that it is indeed the case. Similarly

to what is done in Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (2011b), I estimate the model in first

differences. I let ∆ be a first difference operator so that, for example, ∆NCt = NCt − NC(t−1) .

Unless otherwise noted, the vector of control xCt includes the share of the population that

is 20 and older, the share of the population employed in manufacturing and the share of the

population having the baccalaureate or more.

4.2

Main Results on Turnout

Table 1 presents my baseline results (all specifications include election-state fixed effects and

city-level demographic controls). Column 1 shows the effect of one additional newspaper on

local turnout: I find that one additional newspaper decreases turnout by approximately 0.3

percentage point. In column 2 I focus on newspaper entries. When considering only entries I

find that the effect of an entrant on the market is minus 1.1 percentage points.

A potential concern might come from the fact that the effect of an increase in competition may be different whether the entrant newspaper is owned by the same owner than the

incumbent newspaper or by a different owner. In Column 3, I focus on owner entries. When

considering only owner entries I find that the effect of an entrant on the market is minus 1

percentage points, i.e. of the same order of magnitude than the effect in column 2.

A crucial robustness test consists in estimating the impact of a future change in the news

market on current turnout. Table 2 shows the impact of a change in newspaper competition

on turnout at the previous election (falsification test). The coefficients I obtain are all non

significant and of an order of magnitude much smaller than the ones in Table 1. This suggests

that changes in the number of newspapers are not driven by election results and brings

confidence in interpreting the coefficients of Table 1 as causal effects.

11

Results are also robust to 2-ways clustering at the county-election level and are available from the author

upon demand.

15

D.Number of Newspapers

Entry/Exit

Controls

Election-State FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

D.Turnout

b/se

-0.004∗∗

(0.002)

All

Yes

Yes

0.27

5228

87

(2)

D.Turnout

b/se

-0.011∗∗∗

(0.003)

Only Newspaper Entry

Yes

Yes

0.27

4114

87

(3)

D.Turnout

b/se

-0.010∗∗∗

(0.003)

Only Owner Entry

Yes

Yes

0.28

3905

87

Table 1: Impact of Competition on Turnout at Local Elections

Notes: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by county. Time period

is 1947-2008. Models are estimated in first differences. All specifications include election-state fixed effects and

demographic controls.

D.Number of Newspapers

Entry/Exit

Controls

Election-State FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

LD.Turnout

b/se

-0.001

(0.003)

All

Yes

Yes

0.36

3287

87

(2)

LD.Turnout

b/se

-0.002

(0.008)

Only Newspaper Entry

Yes

Yes

0.37

2495

87

(3)

LD.Turnout

b/se

0.003

(0.005)

Only Owner Entry

Yes

Yes

0.38

2481

87

Table 2: Falsification Test. Impact of Competition on Turnout at Local Elections

Notes: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by county. Time period

is 1947-2008. Models are estimated in first differences. All specifications include election-state fixed effects and

demographic controls. The dependent variable is turnout at the previous election (falsification test).”

16

4.2.1

Diagnosing Bias Using Pre-trends

17

Pre-trends are a standard diagnostic for bias in panel data models. If the relationship

between ∆NCt and ∆yCt comes only from a causal effect, ∆NCt cannot be correlated with

past values of ∆yCt . On the contrary, if the observed relationship is driven by omitted

components, ∆NCt and past values of ∆yCt may be correlated.

In Figure 1 I plot the coefficient αk from the following specification:

∆yCt =

+1

X

αk ∆NC(t−k) + δ∆xCt + ∆µrt + ∆εCt

(4)

k=−1

where yCt is the change in local turnout per eligible voters and other terms are defined

as in equation (3). The prediction that newspaper entry decreases turnout correspond at the

negative spike in the plot at k = 0. It appears that there are no significant trends before or

after the event.12

4.2.2

Interaction with Market Structure

Table 3 shows how our estimated effects vary with the extent of market competition. The

model is identical to the one in Table 1, except that the independent variables of interest

are a set of indicators for the number of newspapers in the county. Interactions with the

market structure are identified by variation in the effect of entries/exits on turnout according

to the number of newspapers in the county at election t − 1. If there are no other sources of

heterogenity in the effect of newspaper entries/exists that are correlated with the number of

newspapers prior to the event, then (under our maintained assumption) these parameters can

be taken as causal estimates of the effect of the number of competing newspapers on voter

turnout.

We find no statistically significant effect of the entry or exit of a county’s second newspaper.

On the contrary, the marginal effect of the third and the fourth newspapers are negative and

statistically significant. The entry or exit of the third newspaper has a significant negative

effect of 0.8 percentage points (columns 2 and 4). The marginal effect of the fourth newspaper

is slightly lower, with a point estimate of minus 0.7 percentage points (columns 3 and 4).

In the next section I open the black-box of news-making to understand this finding.

5

Opening the Black-Box of News-Making

There is a growing concern that the quality of the media might have decreased during the

last decades, at the exact same time when the number of media available was increasing and

the media market became more competitive. Indicative is the contemporaneous increase in

the number of television channels and the often perceived decrease in quality, exemplified by

12

With only 11 elections in the sample, it is not possible to estimate equation (4) with a k higher than 1.

18

Change in Turnout per Eligible Voter

-0.04 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0

0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04

-12

-6

0

+6

Years Relative to Change in Number of Newspapers

+12

Notes: The Figure shows coefficients from a regression of change in turnout per eligible voters, controlling for demographics, on a vector of leads and lags of the change in the number of newspapers (see equation (4) for details). Models

include state-election fixed effects. Error bars are +/− 1.96 standard errors. Standards errors are clustered by county.

Time period is 1947-2008.

Figure 1: Local Turnout and Newspaper Entries.

D.>=2 newspapers

(1)

D.Turnout

b/se

0.002

(0.005)

(2)

D.Turnout

b/se

-0.008∗∗

(0.004)

D.>=3 newspapers

D.>=4 newspapers

Controls

Election-State FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(3)

D.Turnout

b/se

Yes

Yes

0.27

5228

87

Yes

Yes

0.27

5228

87

-0.007∗

(0.004)

Yes

Yes

0.27

5228

87

(4)

D.Turnout

b/se

0.001

(0.005)

-0.008∗∗

(0.003)

-0.007∗

(0.004)

Yes

Yes

0.27

5228

87

Table 3: Turnout Effects by Number of Newspapers

Notes: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by county. Time period

is 1947-2008. Models are estimated in first differences. All specifications include election-state fixed effects and

demographic controls.

19

the multiplication of tabloid talk shows and emergence of ”Reality” television, both in France

and in the United States.

The widely reported scandal of USA Today (one of the main daily newspaper of the US)

star reporter Jack Kelley – nominated five times for a Pulitzer Prize – who fabricated substantial portions of a number of major stories and lifted quotes from competing publications

during more than ten years, illustrates this recent perception of a decrease in news quality.

Jones (2010) refers to another – but very similar – scandal, the one of Jayson Blair, a New

York Times reporter who “had managed to find a crease in the paper’s editorial oversight and

hidden out in it like a lizard in a crack”. He documents extensively how, by the late 1990s,

local TV had all but abandoned covering politics and policy, network television news having

cut foreign bureaus and replacing experienced reporters with less experienced ones. According to him, newspapers had similarly changed as a result of a more competitive environment,

cutting the newsroom to help keep profit margins at a high level.

In this section, I open the black-box of news-making to understand why more newspaper

competition leads to a lower provision of information. I first establish the existence of a

strong ”business-stealing effect”: one more newspaper in a county reduces the circulation of

incumbent newspapers in the county by nearly 25%. Then I study how it affects newspaper

operating expenses and the number of journalists. Consistent with the business-stealing effect,

I find that more competition reduces the number of journalists of incumbent newspapers

without increasing the overall number of journalists in the county. I next show that, by

reducing the number of journalists, an increase in competition reduces the production of news

by newspapers as measured by the total number of articles by issue and the total length of each

newspaper issue. Moreover, within this production of news, more competition also reduces the

share of articles on information (and increases the share of articles on entertainment).Finally

I find that more competition leads to an increase in newspaper differentiation. Overall this

seems consistent with the predictions of the model.

5.1

5.1.1

Competition and Newspaper Profitability

Three Different Levels of Analysis

Given the fact that a number of newspapers circulate across nearby counties, there are three

possible outcomes of interest:

1. County-level outcomes: data are aggregated over newspapers at the county level.

2. Newspaper-level outcomes: data are newspaper-level data. The number of newspapers – the extent of competition on the news market – is measured as the number of

newspapers in the county in which the newspaper is headquartered.

20

3. Newspaper*County-level outcomes: data for each newspaper is disaggregated between the counties in which it circulates.

Computing newspaper*county-level and the county-level outcomes is not an issue when

the only newspapers circulating in a county are headquartered in this county and do not

circulate outside. It is more problematic when a newspaper circulates across nearby counties.

In this case I use data on geographical dispersion of circulation and, for each given newspaper,

I assign to each county in which it circulates a percentage of the value of the variable (e.g. the

number of journalists, total sales, operating expenses,...) equal to its share of the newspaper

circulation.

5.1.2

The Impact on Circulation and Readership

The entry of a newspaper on a market may have a negative impact on incumbent newspapers

if there is a “business-stealing effect”: the total circulation of the entrant newspaper exceeds

the increase in the news market total circulation. Table 4 presents regression estimates of α

from equation (3) with different dependent variables. Models are estimated using OLS with

year and county fixed effects and standard errors are clustered at the county level. I focus on

the time period 1964-2011 (one time unit represents one calendar year) since I do not have

data on the geographical dispersion of circulation before 1964.

In Table 3(a), the dependent variable yct is the total circulation in the county (aggregated

over newspapers) normalized by the number of eligible voters. I expect the sign of the coefficient to be positive or nul. The size of the coefficient is informative about the magnitude

of the “business-stealing effect” (the lower the coefficient, the higher the effect). The results

show that there is a strong business-stealing effect: the number of newspapers in the county

has no statistically significant effect on the total circulation in the county, whether or not I

include demographic controls (columns (3) and (4)).

In Table 3(b), the dependent variable is the individual circulation of each newspaper in

the county ynct . Given that I find that total circulation does not increase with a new entrant,

I expect the sign of α to be negative and statistically significant. With no controls, I find that

one more newspaper in the county reduces the circulation by eligible voters of the newspapers

in the department by approximately 2 percentage points (column 1). Including demographic

controls does not change the coefficient (column 2).

The average circulation of a newspaper in a county during this time period (1964-2011)

representing 9% of the eligible voters (Appendix Table 11), this means that one more newspaper in the county reduces the circulation of incumbent newspapers by nearly 25%. There

is an important business-stealing effect.

As I underlined above, having data on both newspaper circulation and readership from

1957 to 2011 I can compute the ratio of reported readership to circulation. I find that, on

21

(a) Panel A: Total County Circulation Per Eligible Voter

Number of Newspapers

Demographic Controls

Year FE

County FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

Total County Circulation

b/se

-0.005

(0.005)

No

Yes

Yes

0.66

9520

87

(2)

Total County Circulation

b/se

-0.003

(0.005)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.71

9520

87

(b) Panel B: Newspaper Circulation Per County and Eligible Voter

Number of Newspapers

Demographic Controls

Year FE

County FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

Newspaper Circulation

b/se

-0.020∗∗∗

(0.003)

No

Yes

Yes

0.31

9002

87

(2)

Newspaper Circulation

b/se

-0.019∗∗∗

(0.002)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.31

9002

87

Table 4: Impact of Competition on Newspaper Circulation

Notes: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by department. Time

period is 1964-2011. Models are estimated using OLS. All specifications include year and county fixed-effects.

In Panel A, the dependent variable yct is the total circulation in the county (aggregated over newspapers)

normalized by the number of eligible voters. In Panel B, the dependent variable ynct is the individual circulation

of each newspaper in the county normalized by the number of eligible voters.

22

average, each copy is read by 2.8 individuals (with a standard deviation of 0.6). Hence the

average entry of a newspaper reduces the readership of incumbent newspapers by eligible

voters by approximately 6 percentage points.

5.1.3

The Impact on Revenues, Expenses and the Number of Journalists

In this section I estimate the impact of the number of newspapers on operating expenses,

revenues and the number of journalists using as before OLS with newspaper and year fixed

effects. I first study the impact of the number of newspapers on the costs and revenues of

each individual newspaper (newspaper-level analysis). I next estimate the “overall” impact of

changes in competition, summing operating revenues, expenses and the number of journalists

over newspapers to obtain their aggregate values at the county level (county-level analysis).

Table 5 presents OLS regression estimates of α from equation (3) for the time period

1984-2009 with different dependent variables.

In Table 4(a) column (1) the dependent variable ynt is newspaper’s total operating revenues. Nct is the number of newspapers in the county in which the newspaper is headquartered. The result shows that operating revenues decrease with the number of newspapers in

the department. An increase in the number of newspapers on the news market by 1 leads

to a decrease in operating revenues by more than 3,000 thousand euros on average, i.e. 4%

of a standard deviation. The negative impact on operating expenses is of the same order of

magnitude (column (3)), as well as the negative impact on the number of employees (4.2% of a

standard deviation) (column (4)). The impact on sales is more important, since it represents

more than 8% of a standard deviation (column (2)).

One could argue that the difference in the number of employees may be more than compensated by the fact that journalists in a more competitive environment are more skilled or

better paid. In column (5), I look at the impact of a change in the number of newspapers on

the total payroll. The result shows that one additional newspaper decreases the payroll by

nearly 963 thousand euros, i.e. 3% of a standard deviation.

Table 4(b) presents regression estimates of α from equation (3) at the county level. Indeed,

while the results above show that an increase in competition decreases the revenues and

expenses of newspapers facing a more competitive news market, one still needs to check that

at the aggregate market level the total number of journalists or total operating expenses are

not higher after the entry of a new newspaper. The results show that overall, when variables

are aggregated at the county level, there is no statistically significant effect of a change in the

number of newspapers (columns 1 to 5).

Finally in Table 4(b) I check the consistency with the previous results by presenting

regression estimates of α from equation (3) at the newspaper/county level. In column (1),

the dependent variable ycdt is newspaper’s n operating revenues realized in county c in year

23

t. Given the results in Table 4(a), I except the coefficient to be negative and statistically

significant. The results show that there is indeed a negative effect of an increase in the

number of newspapers on newspaper revenues, sales, expenses and number of journalists.

In the next sub-section I try to understand how, through its impact on the number of

journalists, competition impacts quantitatively the production of information.

5.2

5.2.1

Newspaper Content Analysis

Evidence from the Size of Newspaper Issues

As a first evidence of how on the one hand the number of journalists, and on the other

hand the degree of competition on the news market, affect the production of information by

newspapers, I compute different indicators of the size of newspaper issues: (i) the number of

words by newspaper front page (daily data for 54 newspapers over the period 2006-2012) ; (ii)

the number of articles by newspaper issue and (iii) the total number of words by newspaper

issue (daily data for 22 newspapers over the period 2005-2012). I use two different datasets

to study the impact of the number of journalists: (i) the number of journalists data (24

newspapers over the period 2005-2011); and (ii) the total number of employees data (50

newspapers over the period 2005-2011). As I underline above, there is a strong positive

correlation between the total number of employees and the number of journalists working for

a newspaper.

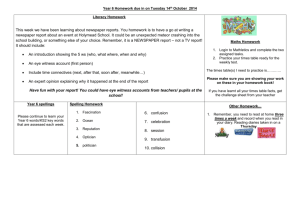

Evidence from Newspaper Front Page I first study the impact of the number of journalists on the total number of words per newspaper front page. The number of words on front

pages is a good indicator of the total size of newspaper issues, since the newspapers often

print the first few paragraphs of articles, that are then continued in later pages: the higher

the number of paragraphs on the front pages, the higher the number of articles in the issue.

Figure 2 shows anecdotal evidence of the strong correlation that exists between the number

of journalists working for a newspaper, and the number of words on the front page of this

newspaper. I plot for the same date (October 2nd, 2012) the front page of four different

newspapers: two national newspapers (the New York Times and Le Monde), and two local

newspapers (L’Eveil de la Haute Loire and Ouest France). These front pages illustrate very

clearly the positive correlation: while newspapers with an important newsroom like the New

York Times (1,150 journalists) have a lot of words and paragraphs of articles then continued

in later pages on their front page, while newspapers with a very small newsroom like the

Eveil de la Haute Loire (26 articles) have very few words on their front page and only large

size photos or advertisements. Moreover, it is useful to underline that this is not driven by

differences between local and national newspaper. Ouest France, a local daily newspaper,

24

(a) Panel A: Total Newspaper Costs and Revenues

Number of Newspapers

Year FE

Newspaper FE

R-sq

Observations

N

(1)

Revenues

b/se

-3175∗∗∗

(537)

Yes

(2)

Sales

b/se

-4065∗∗∗

(1012)

Yes

(3)

Expenses

b/se

-3409∗∗∗

(533)

Yes

(4)

Employees

b/se

-21∗∗∗

(6)

Yes

(5)

Payroll

b/se

-963∗∗∗

(310)

Yes

Yes

.9693148

1028

Yes

.8871496

842

Yes

.967685

1028

Yes

.9504607

1028

Yes

.9629545

1028

(b) Panel B: Total County-Level Costs and Revenues

Number of Newspapers

Demographic Controls

Year FE

County FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

Revenues

b/se

-910

(994)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.95

1043

38

(2)

Sales

b/se

-1365∗

(712)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.92

813

38

(3)

Expenses

b/se

-1296

(908)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.96

1042

38

(4)

Employees

b/se

-5

(9)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.94

1044

38

(5)

Payroll

b/se

-582

(600)

Yes

Yes

Yes

0.95

1043

38

(c) Panel C: Newspaper∗County Costs and Revenues

Number of Newspapers

Demographic Controls

Year FE

County FE

R-sq

Observations

Clusters

(1)

Revenues

b/se

-2501∗∗

(1063)

Yes

Yes

Yes

.7045631

2978

72

(2)

Sales

b/se

-2266∗∗∗

(583)

Yes

Yes

Yes

.6683123

2380

71

(3)

Expenses

b/se

-2542∗∗

(1020)

Yes

Yes

Yes

.7246147

2976

72

(4)

Employees

b/se

-18∗∗

(8)

Yes

Yes

Yes

.6834008

2981

72

(5)

Payroll

b/se

-997∗

(516)

Yes

Yes

Yes

.6638443

2981

72

Table 5: Impact of Competition on Newspaper Costs and Revenues

Notes: * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01. Time period is 1984-2009. Models are estimated using OLS. All

variables (excepted the number of employees) are in (constant 2009) thousand euros. In Panel A, the dependent

variables are values for newspapers. Standard errors in parentheses are robust and specifications include year

and newspaper fixed-effects. In Panel B, dependent variables are values for counties. In Panel C, dependent

variables are values for newspapers by counties. In Panel B and C, standard errors in parentheses are clustered

by county and specifications include county-level demographic controls, year and county fixed-effects.

25

with a larger newsroom than Le Monde (561 against 285 journalists) has also more words on

its front page.

From an empirical point of view, the main advantage of using front pages – even if they

do not offer as much information as the entire content of news issues – is that I have more

data available for front pages, with data for 51 newspapers, i.e. mainly all the French local

daily newspapers.

In Figure 3, I plot for each newspaper the average annual total number of words on newspaper front pages compared with the newspaper’s number of journalists (3(a)) and the newspaper’s total number of employees (3(b)). There is much more data points when considering the

total number of employees since I have more data available for this variable than for the number of journalists. I find a positive correlation between the number of journalists/employees

and the total number of words on the frontpage: the more journalists/employees working for

a newspaper, the more words on the front page. Second, by plotting separately the correlation for newspapers in a county with a monopoly (“blue Plus” symbols) and newspapers in a

county with competition (“red dots” symbols), I find that this positive correlation is driven

in part by monopolistic newspapers which have much more journalists (as underlined above)

and produce a higher number of articles per issue.

I perform a regression analysis below to confirm this finding.

Evidence from the Size of Newspaper Issues

26

CMYK

Nxxx,2012-10-01,A,001,Bs-4C,E3

Late Edition

Today, partly sunny, a warmer afternoon, high 72. Tonight, increasing clouds, low 61. Tomorrow, mostly cloudy, a couple of showers, high

73. Weather map is on Page A24.

VOL. CLXII . . No. 55,911

© 2012 The New York Times

$2.50

NEW YORK, MONDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2012

Seeking Return PAYROLL TAX RISE

Of Art, Turkey FOR 160 MILLION

Jolts Museums

MISTAKEN FAITH

IN SECURITY SEEN

AT LIBYA MISSION

IS LIKELY IN 2013

Complaints by Louvre

and Met Over Tactics BREAK IS SET TO EXPIRE

By DAN BILEFSKY

ISTANBUL — An aggressive

campaign by Turkey to reclaim

antiquities it says were looted

has led in recent months to the

return of an ancient sphinx and

many golden treasures from the

region’s rich past. But it has also

drawn condemnation from some

of the world’s largest museums,

which call the campaign cultural

blackmail.

In their latest salvo, Turkish officials this summer filed a criminal complaint in the Turkish

court system seeking an investigation into what they say was the

illegal excavation of 18 objects

that are now in the Metropolitan

Museum of Art’s Norbert Schimmel collection.

Last year, Turkish officials recalled, Turkey’s director-general

of cultural heritage and museums, Murat Suslu, presented

Met officials with a stunning ultimatum: prove the provenance of

ancient figurines and golden

bowls in the collection, or Turkey

could halt lending treasures. Turkey says that threat has now

gone into effect.

“We know 100 percent that

these objects at the Met are from

Anatolia,” the Turkish region

known for its ancient ruins, Mr.

Suslu, an archaeologist, said in

an interview. “We only want back

what is rightfully ours.”

Turkey’s efforts have spurred

an international debate about

who owns antiquities after centuries of shifting borders. Museums

like the Met, the Getty, the

Louvre and the Pergamon in Berlin say their mission to display

global art treasures is under

siege from Turkey’s tactics.

Museum directors say the repatriation drive seeks to alter accepted practices, like a widely

Continued on Page A3

JIM YOUNG/REUTERS

Ryder Cup Snatched

Martin Kaymer capped Europe’s last-day rally. Page D1.

BEFORE BENGHAZI RAID

Neither Party Supports

Extending a Measure

Into Next Year

Response to June Bomb

Raised Confidence in

Local Guards

By ANNIE LOWREY

This article is by Eric Schmitt,

David D. Kirkpatrick and Suliman Ali Zway.

WASHINGTON — Regardless

of who wins the presidential election in November or what compromises Congress strikes in the

lame-duck session to keep the

economy from automatic tax increases and spending cuts, 160

million American wage earners

will probably see their tax bills

jump after Jan. 1.

That is when the temporary

payroll tax holiday ends. Its expiration means less income in families’ pocketbooks — the tax increase would be about $95 billion

in 2013 alone — at a time when

the economy is little better than it

was when the White House

reached a deal on the tax break

last year.

Independent analysts say that

the expiration of the tax cut could

shave as much as a percentage

point off economic output in 2013,

and cost the economy as many as

one million jobs. That is because

the typical American family had

$1,000 in additional income from

the lower tax.

But there is still little desire to

make an extension part of the negotiations that are under way to

avert the huge tax increases and

across-the-board spending cuts,

known as the fiscal cliff, that will

start in January without a deal.

For example, without any action,

the Bush-era tax cuts will expire

and the military and other domestic spending programs will

be reduced.

“This has to be a temporary

tax cut,” said Timothy F. Geithner, the Treasury secretary, testifying before the Senate Budget

Committee this year and voicing

the view of many in the White

House and on Capitol Hill. “I

don’t see any reason to consider

supporting its extension.”

The White House has not

pushed for an extension. “We’ll

evaluate the question of whether

we need to extend it at the end of

the year when we’re looking at a

whole range of issues,” Jay Carney, the White House press secretary, told reporters last month.

The original point of the payroll tax holiday was to stimulate

consumer spending and aid middle-income households. But now

Congress needs the money as it

struggles with vast deficits and

believes the economy can withContinued on Page A3

TOP, BRIAN SNYDER/REUTERS; ABOVE, DAMON WINTER/THE NEW YORK TIMES

Only 2 Days Left for Cramming

As President Obama and Mitt Romney began final preparations for their debate on Wednesday, a

look at previous debates shows that altering the course of a race has been no easy task. Page A13.

‘North Dakota Nice’ Plays Well in Senate Race

By JONATHAN WEISMAN

MINOT, N.D. — Heidi Heitkamp, a Democratic Senate candidate, called Leonard Rademacher a few weeks ago looking

for his vote, but Mr. Rademacher,

a 74-year-old retiree, was feeling

ill, so Ms. Heitkamp called him

back.

“I said: ‘Heidi, save your

breath. I’m voting for you,’” Mr.

Rademacher recalled, marveling

at her personal attention. “I don’t

necessarily agree with her, but I

trust her.”

Gary Volk backed Ms. Heitkamp, a former state attorney

general, after she sat for four

hours on a slab of concrete next

to what was once his house, lis-

tening to his struggles to recover

from catastrophic flooding last

year. Larry Windus’s mind was

made up by an encounter with

her opponent, Representative

Rick Berg, a Republican, that

ended with the candidate turning

his back on him.

“He’s not very personable,”

said Mr. Windus, 55, a dishwasher at Charlie’s Main Street Cafe

here.

Senate Republicans considered

the state in their column when

Senator Kent Conrad, a veteran

Democrat, announced his retirement last year. But with shoe

leather, calibrated attacks and

likability — an intangible that

goes far in North Dakota — Ms.

Heitkamp has made this a real

fight. Though North Dakota is

Proudly Bearing Elders’ Scars,

Their Skin Says ‘Never Forget’

deeply conservative and is on no

one’s presidential map as a question mark, this race could be one

of the biggest surprises of the

2012 contests. And, like all close

races this year, it could help decide control of the Senate.

Even the National Republican

Senatorial Committee conceded

in its most recent attack ad here

that Ms. Heitkamp is making

headway. “Heidi Heitkamp: You

might like her, but on the issues

she’s wrong for North Dakota,” it

said.

The contest — the state’s first

competitive one since 1986 and

probably its nastiest in modern

history — features two very different politicians with very differContinued on Page A14

Shift by Cuomo on Gas Drilling

Prompts Both Anger and Praise

By DANNY HAKIM

By JODI RUDOREN

JERUSALEM — When Eli

Sagir showed her grandfather,

Yosef Diamant, the new tattoo on

her left forearm, he bent his head

to kiss it.

Mr. Diamant had the same tattoo, the number 157622, permanently inked on his own arm by

the Nazis at Auschwitz. Nearly 70

years later, Ms. Sagir got hers at

a hip tattoo parlor downtown after a high school trip to Poland.

The next week, her mother and

brother also had the six digits inscribed onto their forearms. This

month, her uncle followed suit.

“All my generation knows

nothing about the Holocaust,”

said Ms. Sagir, 21, who has had

the tattoo for four years. “You

talk with people and they think

it’s like the Exodus from Egypt,

ancient history. I decided to do it

to remind my generation: I want

to tell them my grandfather’s

story and the Holocaust story.”

Mr. Diamant’s descendants are

among a handful of children and

grandchildren of Auschwitz survivors here who have taken the

step of memorializing the darkest

days of history on their own bodies. With the number of survivors

here dropping to about 200,000

from 400,000 a decade ago, institutions and individuals are grappling with how best to remember

the Holocaust — so integral to Israel’s founding and identity — after those who lived it are gone.

Rite-of-passage trips to the

death camps, like the one Ms.