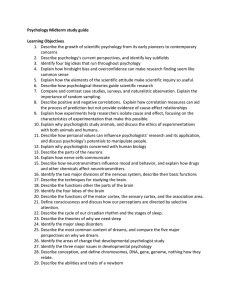

CLINICAL STUDENT HANDBOOK

advertisement