The Ethics of War. Part II: Contemporary Authors and Issues Endre Begby

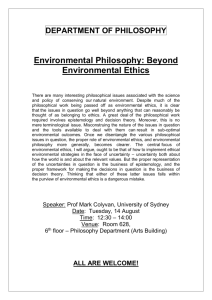

advertisement