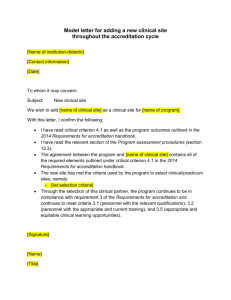

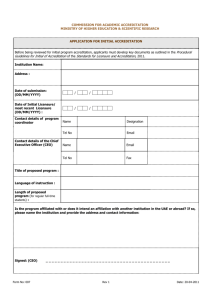

Proposal for accreditation of pharmacy careers in Latin America

advertisement