1 ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS INTO HIGHACCESS LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS INTO HIGHACCESS

LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

A DISSERTATION

SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE DEGREE

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION

BY

JASON ROSEBERRY

DR. SERENA SALLOUM ADVISOR

BALL STATE UNIVERSITY

MUNCIE, IN

MAY 2016

1

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS

A DISSERTATION

SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE DEGREE

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION

BY

JASON ROSEBERRY

DISSERTATION ADVISOR: DR. SERENA SALLOUM

APPROVED BY:

____________________________________ ____________

Dr. Serena Salloum, Committee Chairperson Date

____________________________________ ____________

Dr. John Ellis, Committee Member Date

____________________________________ ____________

Dr. Michael O’Hara, Committee Member Date

____________________________________ ____________

Dr. Jeff Swensson, Committee Member Date

____________________________________ ____________

Dr. Robert Morris, Committee Member Date

BALL STATE UNIVERSITY

MUNCIE, INDIANA

MARCH, 2, 2015

2

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 3

ABSTRACT

As schools have placed an increased emphasis on instructional technology, the amount of money spent on hardware and student devices in classrooms has increased significantly ( Nagel,

2014). Because a dministrators are underestimating the instructional shift required for effective integration of these devices, they are not allocating enough time and resources for teacher professional development (Sawchuck, 2010). This has contributed to a digital divide between teachers in districts across the state, and, even, within grade levels at the same school. The result is an epidemic of classrooms with high access to technology, but low use among educators.

The purpose of this study was to explore how two highlyregarded Indiana school districts prepared their middle school teachers to integrate technology. Mixed methods were used to discover how teacher and administrators described their professional development, and how closely these descriptions reflected ten characteristics of effective professional development identified in the literature review. T he study also attempted to operationalize the ISTET standards as a method for approximating practices. Data were collected using teacher surveys, classroom observations, and focus groups.

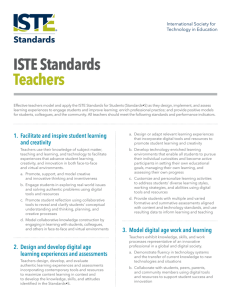

Both schools emphasized a standardized format (Gaible & Burns, 2005) for their trainings. While this worked well for introducing new content, this single session approach did not allow for other effective strategies identified in the literature review such as time for reflection (Tillema, 2000), increased teacher voice regarding content (Opfer & Pedder, 2011) , and varied delivery methods (Schrum & Levin, 2013). The descriptions within the ISTET

Standards were found useful for identifying instructional traits, but the results skewed towards identifying teacherdirected learning experiences. As far as the characteristics of effective

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS professional development from the literature review, the study found that these two schools emphasized learning experiences that considered teacher beliefs (Desimone, 2009), were

embedded within job responsibilities (Nuthall & AltonLee, 1993) , measured teacher growth

(Opfer & Pedder, 2011), and focused on student learning outcomes ( Clarke & Hollingsworth,

2002).

4

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This challenging process would not have been possible without the efforts from an army of people. First, thank you to Dr. Ellis for helping me a craft a literature review, Dr. Swensson for jumping into the open seat, and Dr. O’Hara for putting up with me since I was 19. Their thoughtful feedback and suggestions placed their mark on my work. A very special thank you to my chair, Serena Salloum for her knowledge, encouragement, patience, and rigorous comments.

Serena was always a catalyst and inspiration for my writing and research throughout the process.

I am also grateful for the contributions and patience from my FiveStar family. A special nod to my boss, Jim Benson, who brought me into a supportive company where I could bring these big ideas to life. I am also grateful for my “old” boss, Kristin Nass, who was so influential at modeling what amazing school leadership looks like in “real life.”

The warmest of acknowledgements to my friends and family for their love and support.

Eli Beardsley was a colleague and counselor. My parents, Danny and Norma Roseberry, are perhaps the greatest parents and most supportive people on the face of the earth. My little sister,

Marcy Kist, provided a willing target for witty verbal stress release, and John L. Smith was always good for a welltimed distraction.

Finally, I want to acknowledge the love and patience of my three “B” boys (Beardsley,

Buerk, and Brooks), and my wife, Hannegan. You have shared me for many years with this research, and I now look forward to quality time without divided attention. I don’t know how

people get by in their lives without a person like Hannegan. I am thankful God blessed me with her love and support. She inspires me to be a better person than I was yesterday.

5

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………..

5

LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………....

89

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………….

10

Statement of the Problem………...…………………………………………………….

11

Research Questions………...…………………………………………………………..

13

Definition of Terms………...…………………………………………………………..

13

Theoretical Framing………...………………………………………………………….

14

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW 17

Overcoming the Digital Divide………...……………………………………………… 17

Characteristics of Effective Professional Development for Teachers………………….

20

Professional Development Specific to Technology Integration………………………..

30

Technology Training and Transformational Learning Theory………………………....

37

Standards and Measurement of Professional Development………………………........

38

Conclusion………...…………………………………………………………………....

40

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY…………………………………....

42

Research Questions…………………………………….................................................

42

Research Design……………………………………......................................................

42

Description of the Sample…………………………………….......................................

43

The Instruments…………………………………….......................................................

46

Data Collection……………………………………........................................................

48

Data Analysis……………………………………..........................................................

49

The Researcher’s Role…………………………………….............................................

50

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS……………………………………......................................

52

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 7

Rogers Middle School…………………………………….............................................

52

Summary…………………………………….................................................................

76

Stark Middle School……………………………………...............................................

78

Summary…………………………………….................................................................

99

Comparison of Schools……………………………………...........................................

101

Combined Dataset of Both Schools………………………………….….......................

115

Chapter Summary……………………………………....................................................

115

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSIONS…………………………………….............................

117

Research Questions…………………………………….................................................

117

Teacher Preparation (R1)……………………………………........................................

118

ISTET Standards (R2)……………………………………............................................

120

Ten Identified Traits for Effective Professional Development (R3)...............................

122

Implications for Policy....................................................................................................

128

Limitations.......................................................................................................................

130

Implications for Theory...................................................................................................

130

Suggestions for Future Research.....................................................................................

131

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................

134

APPENDIX...........................................................................................................................

142

Appendix A Survey......................................................................................................

142

Appendix B Observation Tool.....................................................................................

146

Appendix C Focus Group Questions...........................................................................

147

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS

LIST OF TABLES

8

Table 3.1: Comparison of District Demographics..…………………………….……………….46

Table 4.1: Rogers Middle School Survey/Observation Data by ISTET Standard …...…..…5556

Table 4.2: Rogers Middle School Grade Level Comparison of Means ……………..…....….….57

Table 4.3: Rogers Middle School Years of Experience Comparison of Means ………….…..…58

Table 4.4: Rogers Middle School Subject Area Comparison of Means…. …..…….……...……59

Table 4.5: Ten Identified Traits for Effective Professional Development: Rogers Middle

School………………………………………………………………………………….……... …66

Table 4.6: Rogers Middle School SAMR Levels (Observed) …………………….....……..……76

Table 4.7: Stark Middle School Survey and Observation Data by ISTET Standard ..….....….…80

Table 4.8: Stark Middle School Grade Level Comparison of Means... …………………....….…82

Table 4.9: Stark Middle School Years of Experience Comparison of Means …….……….…8384

Table 4.10: Stark Middle School Subject Area Comparison of Means ………………………….85

Table 4.11: Ten Identified Traits for Effective Professional Development: Stark Middle

School …………………....……………………………………………………………………... 91

Table 4.12: Stark Middle School SAMR Levels (Observed) ........................................................99

Table 4.13: Comparison of Districts by ISTET Standards ……..…………………………102103

Table 4.14: SAMR Comparison of Schools ………………………………….……………...…104

Table 4.15: Overall Comparison of Means for Schools …………………………...……...……105

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 9

Table 4.16: Comparison of Ten Identified Traits for Effective Professional Development ……106

Table 4.17: Combined Grade Level Comparison of Means …………………………..…......…107

Table 4.18: Combined Years of Experience Comparison of Means …………………....…108109

Table 4.19: Combined Subject Area Comparison of Means ………………………………..….110

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 10

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

In 1975, Intel Corporation founder Gordon Moore observed that throughout the history of technology the number of transistors in a circuit doubles approximately every 18 months

(Willoughby, 2005). This observation that technology was doubling every two years came to be known as Moore’s Law. It was 1981, when two IBM scientists, Gerd Binnig and Heinrich

Rohrer, invented the scanning tunneling microscope (Schechter, 2010). This device was capable of not only reading the surface of each atom, but eventually allowed the scientists to arrange 35

Xenon atoms into the letters “IBM.” On the “Today” show on NBC in 1994, the anchors, Katie

Couric and Bryant Gumbel, could be heard discussing how to pronounce the @ in an email address, and Couric asks, “What is the internet, anyway?” (“1994: Today,” n.d.).

These three examples demonstrate how technology has magnified and changed our culture with every step of its development. As the physical size of our technology has continued to shrink, the role it plays in our life has expanded. A Pew Internet & Tech Survey in April,

2012 revealed that mobile devices are nearly ubiquitous with 88% of adults reporting owning a smartphone (Smith, 2012). Many industries have been forced to embrace the rise in mobile access or face disruption or extinction.

Candice Dodson is the Director of eLearning for the Indiana Department of Education, and the ChairElect for SETDA a national organization for statelevel technology leaders.

During an interview, she commented that there is a strong movement towards increasing the use of educational technology through individual learning devices in schools today (personal communication, November 12, 2015 ). Perhaps the most high profile example of technology

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 11 focused on highaccess learning environments instead of teacher development was the Los

Angeles Unified School District’s 1:1 initiative. The one billion dollar initiative put tens of thousands of iPads in students’ hands. The iPads were confiscated weeks later due to ineffective security, theft, lack of parent communication, and confusion over a $500 million purchase of curriculum from Pearson (Herold, 2014). This led the school district to realize their lack of ability to gauge their readiness, train students and staff on methods and student responsibility, and communicate effectively with parents.

At the time of this writing, Los Angeles Unified hired consultants to gather survey data, interviews with stakeholders, and other data related to the use of the devices in order to make better decisions moving forward. “Districts need to take the time to go through the strategic planning process as they manage change and investigate opportunities for students to use technology in meaningful ways” (C. Dodson, personal communication, November 12, 2015).

Statement of the Problem

Ss schools have placed an emphasis on instructional technology, the amount of money spent on hardware in classrooms has increased significantly. Nationally, educational technology spending increased by an average of 11% (20122013), and schools spent 13 billion dollars on technology in 2013 ( Nagel, 2014). Despite this increased allocation of resources, many educators still do not comprehend the technological shift that has occurred within our culture (C.

Dodson, personal communication, November 12, 2015) . Administrators are placing devices in teachers’ classroom without providing them adequate professional development (Sawchuck,

2010). This lack of effective training has contributed to a digital divide between teachers in districts across the state, and, even, within grade levels at the same school. The result is an

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS epidemic of classrooms with high access to technology, but low use among educators ( Wood,

Mueller, Willoughby, Specht, & Deyoung, 2005).

12

Significance of the Problem

While mobile devices and blended instruction have undeniable potential to expand the accessibility of learning opportunities (Plair, 2008), it is clear that more studies are needed to understand how school districts are preparing teachers to integrate technology to positively impact student learning and instruction (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). Teachers state many reasons for rejecting technology adoption and blended techniques including: not easy to use, changing daily practice is too dramatic, not enough professional development, increased workload, and inability to understand the significance. Gaible and Burns (2005) reported that teacher professional development must be relevant to the problems teachers face and of highquality. They suggest that the training is most often successful when the teachers feel it will increase their productivity and efficacy.

This study identifies effective practices for creating and implementing training to assist educators in incorporating technology into their classrooms. Much of the training currently offered to educators within their school building does not meet their needs as adult learners, and, therefore, is not relevant (Sawchuck, 2010). It has also become clear that good practices for using and teaching with devices and blended instruction are undefined, leading to more confusion and lowquality professional development (R

1

). There are few recognized methods/standards for measuring educator efficacy when it comes to implementing and using new technologies (R

2

). Furthermore, without quality professional learning experiences, it is difficult for teachers to break the highaccess/lowuse cycle seen in schools today (R

3

).

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 13

R

2

R

3

Research Questions

R

1

How did two Indiana school districts that won the IDOE Innovation and Learning Grant prepare their middle school teachers to integrate technology?

How closely does the instruction within these schools align with the ISTET Standards?

How did teachers at these school describe their professional development, and how closely do these descriptions reflect the ten identified practices for effective professional development from the literature review?

Definition of Terms

Important terms in this literature review are digital immigrants, assimilation, highaccess, and learning environments. Along with the many changes in technology and culture that have taken place during the past two decades, there has also been a change in the nature of the student learning (Prensky, 2001). Prensky (2001) observed that the needs of today’s K12 students no longer match the educational system as it was originally designed. With the widespread exposure to technology and social media, today’s students “think and process information fundamentally differently from their predecessors” (p. 1), and that leads him to label current students digital natives . This group is comprised of students in kindergarten through college. At the time of this writing, the age of Prensky's digital natives would be from newborn to approximately 35. The rest (36 and older) were born outside the digital revolution are referred to as digital immigrants . Using this new world analogy, Prensky (2001) goes on to describe digital immigrants as having accents. The degree to which digital immigrants smooth their digital accents will ultimately ascertain their success in engaging with digital natives.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 14

The word assimilation is defined from MerriamWebster as, “to take into the mind and thoroughly comprehend,” and also, “to absorb into the culture or mores of a population or group”

(Assimilation, n.d.). Prensky’s digital native/new world analogy embraces the idea that digital immigrants (regardless of age) must absorb, comprehend, and take into their mind the strategies and tools of our time in order to succeed with today’s students. From my experience as a K12 technology/professional development consultant, most schools refer to their technology initiatives as 1:1 or one student: one device. This term can put too much emphasis on the device, and not enough on student learning with guidance from a facilitator.

The term highaccess refers to classrooms where there is technology available to students and educators. This technology may take the form of laptops, tablets, or any other environment where Internet access is readily available to students. The term learning environment refers to any place or time when a student has potential access to some amount of knowledge and feedback from a facilitator. A highaccess learning environment is one in which a student has at least partial access to online digital curriculum and a facilitator. The definition is not limited by time or location.

Theoretical Framing

Transformational Learning Theory undergirds this study by making a case for adult learning that emphasizes the assimilation of new knowledge through reflection. It is, in fact, a form of adult learning theory that has been used to create a better understanding of professional development involving instructional technology (Dirkx, 1998). This theory was developed by

Mezirow (1991) and used to study learning practices within adults. Transformational Learning

Theory involves learning by reflecting and drawing upon one’s prior knowledge and experiences.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 15

These experiences come to define adult learners, and affect how they assimilate new information they come in contact with as they learn. While a transformational learning experience can sometimes distort existing understanding, through critical reflection, it can also allow adults to reformulate their existing beliefs. In other words, an adult learner’s ability to learn new information is based on their personal level of experience and development within a profession

(Dirkx, 1998). An individual uses their experiences to process new information.

Transformational teaching in an educator’s classroom can be described as the creation of relationships between student, teachers, and knowledge to increase student learning (Slavich &

Zimbardo, 2012).

By respecting a learner’s experiences and giving them a chance to reflect critically on new information, transformational learning can take place. As applied to the topic of adult learners in a highaccess learning environment, one would expect that teacher professional development would be more effective when it meets educators at their specific level of need and or belief, and allows for reflection on the new knowledge. It would also provide clear methods for measuring growth and improvement (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007).

The following chapter will explore differences in learner needs, learning spaces, and methods for creating and implementing professional development opportunities. Chapter Three will present three research questions focused on exploring the professional development methods used by two middle schools in Indiana who were recognized as “innovative” by the IDOE Office of eLearning. It will also describe the methods used to collect and analyze research data.

Chapter Four will explore how closely the instruction methods compares to internationallyrecognized standards created by the International Society for Technology in

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS

Education (ISTE), and the ten identified practices for effective professional development from

Chapter Two.

16

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 17

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter explores the differences in learning styles between generations and identifies ten researchbased practices for effective professional development for educators. First, research concerning barriers to professional learning experiences involving technology integration is examined. Second, there is research on the impact of devices on teacher and student learning.

Next, three different learning spaces are described: onsite, online, and blended. Finally, the benefits and shortcomings of each learning space is shared, and a description of standards currently used to guide technology integration are provided.

Overcoming the Digital Divide

According to Prensky (2001), a digital divide has occurred due to a dissonance in the way that that digital natives and digital immigrants learn. Digital natives prefer to receive information quickly, multitask, read graphics before text, network, receive instant gratification, and play games. Digital immigrants, on the other side, generally prefer slowpaced, stepbystep instructions, one concept at a time, and a more serious tone to their learning.

In past years, Prensky’s ideas on digital natives have been considered controversial.

Most researchers have observed that while the younger generation generally has a greater understanding of technology, their age is not the most significant predictor of success with using it (Brown & Czerniewicz, 2010; Salajan, Schonwetter, & Cleghorn, 2010; Gu, Zhu, & Guo,

2013; Margaryan, Littlejohn, & Vojt, 2011; Yang, & Yuen, 2010) . The digital divide has more to do with having access to the technology and less to do with a generational difference. A thorough definition of the digital divide includes, both, access and use of information technology,

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 18

(Srinuan & Bohlin, 2011) and references the fact that the divide can exist, “between individuals, regions, or countries” (p. 2), as well as students of different ethnicities or socioeconomic status

(Swain, 2003). However, the digital divide may not be as clearcut as it seems.

Ransdell, Kent, GaillardKenney, and Long (2011) performed a study with multiple generations of learners who took an online course in a graduate health science course. The digital immigrants were shown to have better knowledge application and deeper reading of websites required for the course than the other three groups including the digital natives. While this does not mean that digital immigrants are more skilled at using technology than their counterparts, it could mean that the study skills taught and valued by digital immigrants can translate well to the online learning environment.

In order to understand the needs of learners on either side of the divide, it is important to understand how their learning varies from each other. Yang and Yuen (2010) referred to a

“neomillennial learning style” consisting of: fluency in many types of media and communication, preference for collaboration and learning through multiple channels, active learning involving actual experiences/reflection, learning through nonlinear pathways, and the desire to seek and synthesize information themselves (p. 8). Thornburg (2007) reasoned that all learners (digital natives or immigrants) require four different spaces for authentic learning to take place: campfire (lecture), watering hole (discussion), cave (reflection), and life (authentic assessment/practical application).

Thornburg wrote that learning that did not touch all of these metaphorical learning spaces would result in low retention of new information. This model can be used to address the needs of digital native learners by incorporating modern tools into the learning spaces: campfire

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 19

(recorded minilecture), watering hole (online discussion boards, Skype, Google Hangouts, etc.), cave (blogging), and life (digital tools used to demonstrate authentic learning). Thornburg predicted that increased time spent defining and learning in these spaces would result in higher levels of mastery. Additionally, digital immigrants who were more comfortable with linear learning involving textbooks and tangible resources ( Yang & Yuen, 2010), may be moved towards digital native strategies and tools by using these existing learning spaces and reimagining them for new learning experiences.

Meeting digital immigrants at their current level of belief about technology integration and allowing time for reflection aligns with Transformational Learning Theory and the idea of,

“affecting change in a frame of reference” ( Mezirow, 1991, p.5). Experienced educators accumulate a large body of knowledge and experience from their lives and within their classroom. These experiences result in different assumptions or beliefs for how technology can be most effectively used for learning by digital immigrants and digital natives. Thus, the way administrators engage with teachers in learning experiences must be different.

A kindergarten student with limited life and education experience may assimilate new knowledge in a less complex fashion compared to a high school senior who has 12 years of schooling as a reference. A preservice teacher may attempt new strategies more easily since their frame of reference is heavy on knowledge, but light on experience. Veteran digital immigrant educators must receive professional development that respects his or her current level of belief, knowledge, and experience concerning the topic of study ( Slavich & Zimbardo, 2012) .

Although the distinction in learning styles between generations proposed by Prensky

(2001) has faced a great deal of criticism, the concept of a digital divide between those who use

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 20 instructional technology effectively and those who do not is valid. The digital divide is becoming an issue not just between students and teachers, but, more importantly, in districts, schools, and even grade levels (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). Lawless and Pellegrino did not express concern that our students will one day have ubiquitous access to devices for learning.

They did express concern that students may not have ubiquitous access to a teacher who is capable of using technology to reinforce 21st century ideas. This is most likely to occur if the needs of adult learners are considered when professional development is planned and implemented (Mezirow, 1991).

With the widespread adoption of student technology within many districts, schools today are at a crossroads in their educational history (C. Dodson, personal communication, November

12, 2015). Decisionmakers need to understand what is causing the existing digital divide among teachers and contributing to unequal learning experiences for students in today’s classrooms (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). Teachers and administrators need access to examples of districts who have successfully managed the transition and implemented technology that has enhanced the learning experience for students.

Characteristics of Effective Professional Development for Teachers

Gaible and Burns (2005) defined professional development for teachers as, “training which includes ongoing workshops, followup, study, reflections, observations, and assessment”

(p.16). Guskey (2002) expanded on this to include, “study groups, action research, collaborative planning, curriculum development, structured observations, peer coaching, mentoring, and so on” (p. 46). However it is defined, quality professional development is essential to any and all school reforms and movements (Martin, Strother, Beglau, Bates, Reitzes, & Culp, 2010; Reeves

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 21

& Pedulla, 2011; Hedberg, 2011).

Before considering specific research into professional development for instructional technology, there was a need to understand what research points to as effective practices or teacher professional development in general. From the literature reviewed on traditional professional and technologybased professional development, I identified ten common characteristics of effective professional development. This section of the chapter focuses on the seven specific to traditional professional development: contextualized, jobembedded, communitybased, time provided for reflection, focused content, beliefs are respected, and datadriven. Each of these areas is described with supporting research below.

Contextualized . The research stressed the importance of drawing a distinction between content for specific groups and information that is generalizable (Nuthall & AltonLee, 1993;

Opfer & Pedder, 2011). Opfer and Pedder (2011) referred to these different types of professional development as contextualized and decontextualized. Decontextualized training can be various tasks that occur between all educators such as: planning, mutual observation and feedback, and responding to a video of another educator teaching (Gaible & Burns, 2005).

Contextualized professional development consists of learning that can be applied in a small group setting to a specific subject area, grade level, or strategy with a particular student population. In a recent study, 58% of educators reported that they had not received adequate decontextualized training, with 81% reporting that they had never received contextualized professional development (Hutchinson, 2012). While both types of learning are equally important, it is clear that educators need more exposure to contextualized learning experiences.

Gaible and Burns (2005) divided professional development for teachers into three

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 22 categories: standardized, sitebased, and selfdirected. Hooker (2008) gave a detailed description of the characteristics of each. His purpose was to categorize the benefits and limitations of each type of professional development. Standardized professional development includes noncontextualized workshops and training sessions, and is described as having a cascade approach in which the information is generally “thrown” upon participants. Hooker said standardized professional development could be an effective when the intent of the training is to introduce new concepts, model, or build awareness. Limitations to standardized learning included the inability to differentiate, a lack of ongoing support, and low retention by participants.

Hooker (2008) described sitebased professional development as training that is gradual and involves working with an expert in a small group setting. This type of learning is contextualized and emphasizes collaboration and flexibility. Sitebased professional development is recommended when the training needs to move beyond basic awareness and introduction of concepts. This format would work well for developing instructional practices and strategies within specific subject areas and/or grade levels.

The third type of professional development Hooker describes is selfdirected.

Selfdirected learning works well for motivated teachers who are willing to seek out their own experiences and knowledge. Using this format involves allowing the participant to have individual time to research, reflect, and share their findings with other teachers within their contextualized group.

Overall, the most effective professional development for teachers will be differentiated in order to accommodate all preferences for learning and delivery among participants (Schrum &

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 23

Levin, 2013). Gaible and Burns (2005) and Guskey (2002) observed that sitebased and selfdirected professional development are more effective than the standardized workshop style currently popular among school districts (Sawchuck, 2010).

Sawchuck (2010) wrote of a culture of teachers exposed to extensive oneday workshop models of learning that, he observed, were not fully developed as ideas. Sawchuck (2010) argued that educators live in fear of whatever conference their superintendent may next be attending. Sawchuck said that superintendents may lack clear examples of successful implementation, and are thus prone to random acts of professional development. With an unclear focus and continuously shifting topics, educators come to view all forms of professional development as ineffective and a waste of time.

As viewed through the filter of Transformational Learning Theory (Dirkx, 1998), school leaders must respect the beliefs and experiences of veteran teachers around the ineffective, unfocused, and noncontextualized professional development from the past. Leaders will be able to transform learning more effectively by planning teacher learning experiences that are contextualized to the participant’s subject/level. This will allow the participant to reflect more productively on implementation because it addresses their current level of knowledge more specific to their own experiences (Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

JobEmbedded. While the standardized model of professional development can be quite useful for creating awareness, it will seldom result in changes in classroom practice or student performance (Gaible & Burns, 2005). In fact, when teacher learning occurs via a presentation with the intent of passing on general knowledge, it is very unlikely that it will yield a change in practice ( Opfer & Pedder, 2011). Plair (2008) observed that since technologycentered training

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 24 is delivered with the intent of building awareness about concepts or “getting the ball rolling,” the information is too general to get teachers started in their own classrooms. Teachers require contextualized resources, tools, and strategies they can transfer immediately to their classrooms.

Although there is a consensus within the research community that professional learning must now be continuous, social, and related to classroom practices, there is a disparity between research and actual professional learning offered by school administrators (Webster & Wright,

2009).

Webster & Wright (2009) stress the importance of teacher learning that is not based on a single training session, but built into the longterm expectations for the teachers. Gaible and

Burns (2005) referred to this as schoolcentered professional development. While there are multiple reasons for embracing this strategy, some of the most compelling reasons relate to basic knowledge assimilation. For example, in their research on student learning, Nuthall and

AltonLee (1993) coded different types of exposures to knowledge. They found information transferred via lecture or presentation format needed to be reviewed soon and often for retention.

If students were to go two or three days without “hearing” the information from their teacher, they would experience a loss of knowledge. In most cases it took three to four exposures to the same information with less than two or three days between each exposure for longterm learning to occur. When the student was able to relate the topic to other relevant information previously stored, the retention came sooner and without the usual amount of review required.

Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, and Yoon, (2001) found that similar needs were present with adult learners. Their research concluded that teacher learning experiences must contain three instructional moments: time to absorb, time to discuss, and time to practice new knowledge

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS within their own classrooms. A change in teaching practice would not occur unless adequate time for all three moments was provided. It is a stark contrast to the frequent use of single session presentationstyle professional development often used in K12 school districts

(Sawchuck, 2010).

25

Carpenter, Fennema, Peterson, Chiang, and Loef (1989) conducted a study of elementary mathematics teachers to understand how the amount of time teachers were exposed to new learning was connected to student test scores on the new learning. Educators were given professional development specific to elementary mathematics, but there was a great variation in the number of training hours. One group participated in a fourweek summer workshop (80 hours total), and the other group had two, twohour workshops. The group found that students taught by teachers who had participated in the 80hour summer training outperformed the comparison group on a standardized mathematics test (compared to pretest scores). This reinforces Guskey’s (2000) findings that continuous jobembedded professional development that involves many hours over a long period of time is associated with effectiveness (Guskey,

2000).

CommunityBased. One of the key characteristics of standardized professional development is the generalized nature of the information (Gaible & Burns, 2005). The more related the community of learners are to each other, the greater chance of effective professional development experiences (Desimone, 2009). Efficacy increases as the community becomes more deeply related to their common learning. Whatever the efficacy of the training at a school level, it would be even more effective if educators from the same department learned collectively. When training becomes less general and more specific among likeminded

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 26 educators, it increases in efficacy (Opfer & Pedder, 2011; Wright, 2009). Professional development has been shown to be more effective in affecting teacher learning and teacher practice if teachers from the same school, department, or year level participate collectively.

This community concept is often seen in schools today through Professional Learning

Communities (PLCs). PLCs transform the culture of organizations through collaboration, shared mission/goals, persistence, and celebration (Eaker, DuFour, & DuFour, 2002). A PLC involves the entire staff reflecting upon their instructional practices, hopes for student outcomes, and monitoring learning to ensure growth. When community learning is in place, discussions become embedded within the entire school culture. Breaking from teacher isolation and focusing on highperforming teams with common goals builds capacity for individuals and the district/school.

Time Provided for Reflection. Reflection on information has long been a major tenet for education and leadership organizations, but it is also a component of Transformational

Learning Theory (Dirkx, 1998). The most common barrier to providing reflection within school professional development is the lack of time for training. This is why many schools rely so heavily on the standardized training practices (Gaible & Burns, 2005).

Tillema (2000) conducted a study on reflection and learning among studentteacher candidates. For the purposes of this study, Tillema referred to reflection as a discussion among a group of student teachers. In this study, candidates were divided into two groups. One group reflected on what they needed to know about teaching, and then practiced teaching within a classroom. The other group practiced within a classroom, and then reflected on their experiences. Tillema found that reflection after practice had a positive effect on changing

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 27 beliefs, whereas reflection prior to practice did not result in a change in these beliefs.

Tillema’s (2000) findings demonstrated that reflection alone does not affect beliefs, but reflection combined with learning can be powerful. Learning is most effective for educators when the training activities require them to apply the new learning in their classrooms, and then reflect with a small group on the experience (Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

Focused Content. Buckingham (2006) said, “ Clarity is the antidote to anxiety. If you do nothing else as a leader, be clear” (p. 8). Educators today are under a great deal of expectations and pressures due to standardized testing and evaluations. Along with the learning that goes along with these two pillars of modern schools, there are often additional professional development expectations. Desimone (2009) observed that focused content was the greatest predictor for effective professional development for teachers. Opfer & Pedder noticed that school administrators often spend more chasing new ideas time than preparing and streamlining existing content (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). In other words, while the teacher is still attempting to apply and internalize the concepts from new learning, many administrators are already exploring a different idea.

Opfer and Pedder (2011) suggested that maintaining a proper balance between innovation and detailed implementation would make the difference between an organization that learns and one that only attempts new things. School administrators must have a clear vision for what the professional development will look like once it is implemented. When considering this trait in the context of instructional technology, many administrators do not have a clear vision or model of possibility for effective student technology implementation (C. Dodson, personal communication, November 12, 2015).

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 28

Beliefs are Respected/Measure Progress. The research on the final two traits is so closely linked that it is easier to describe them in relation to each other. Opfer and Pedder (2011) found that it is significantly easier to change the beliefs and practices of preservice teachers than inservice teachers. Looking through the filter of Transformational Learning Theory, it is logical that preservice teachers have not had the same number of experiences within a jobembedded context as veteran teachers. This prior learning and experiences can often make the acquisition of new knowledge and changes to instructional practice more difficult for experienced educators

(Dirkx, 1998).

In order to effectively change a teacher’s practice within his/her own classroom, leaders will first have to change the teacher’s belief towards making that change (Raths, 2001; Opfer &

Pedder, 2011). Opfer and Pedder (2011) went one step further and observed that teachers are more likely to seek learning opportunities that match their beliefs. Desimone (2009) referred to this as coherence. The goal of coherence is to match teacher beliefs with the information presented as part of the new learning experience. The knowledge teachers gain within this type of training can then move them from their current beliefs and affect instructional practices.

Wheatley (2002) observed that a teacher’s selfefficacy has an effect on student outcomes. Wheatley suggested teacher professional development needs to initially match educator belief, but then create a disruption or cognitive dissonance in order to affect their feeling of efficacy . Bandura (1994) described selfefficacy as how strongly people felt that they were capable of influencing events that affected them. People who are confident in their abilities approach difficult tasks as challenges and can experience intrinsic motivation to increase interest and engagement in activities. However, if the dissonance is too great, it can result in a negative

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 29 attitude and lack of motivation in the individual.

In their study, Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) reviewed a history of teacher training models that include three main areas: teacher beliefs, teacher practices, and student learning.

They noted that educational programs have historically attempted to begin with belief change as a way of affecting practices to, ultimately, increase student learning. Opfer and Pedder (2011), upon reflecting on the literature, said that, instead, the belief/practice/student learning process is reciprocal and contingent upon each area. In addition, they observed that the process can begin in any one area, affect the following corresponding area, and continue the learning process in a positive manner. Below is a graphic (Figure 1) to assist with visualizing this concept.

Figure. 1. A model of professional growth

A teacher who has a learning experience can enter Figure 1 in any of the three areas

(beliefs, practices, or student learning), but for longterm learning to occur, the professional

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 30 learning experience must result in a change in all three areas (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). In order to measure the effect on student learning, teachers must have a method for collecting and operationalizing data that they find meaningful. When teacher beliefs affect practices and practices affect student learning, then the professional growth is not just circular. The positive impact on student learning once again affects the new teacher beliefs, and this process works as a helix of continuous professional growth for the educator.

These seven identified traits of effective professional development all correspond to the concepts within Transformational Learning Theory. Changing the framework for an experienced educator is a difficult task. While school leaders must consider beliefs/practices and measure student learning related to new learning, they must also prepare to integrate the development throughout the culture of the building. This means focusing training offerings, embedding the professional development outcomes within teachers’ classrooms, building communities with shared beliefs through contextualized training, allowing time for reflection, and measuring the related student learning.

Professional Development Specific to Technology Integration

Technology integration as a strategy for teaching and learning has the potential to affect all activities in the classroom in a positive manner (C. Dodson, personal communication,

November 12, 2015). It is important to understand that with a new and evolving topic such as instructional technology, there may never truly be best practices, “Only good practices that change frequently” (Prensky, 2012, p. 3). Prensky (2012) wrote that the best strategy is for teachers to constantly think and consider new ways devices may be used to amplify the student learning experience. It many ways, this new world requires us to always be in beta (testing

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 31 phase). The days of laminating lessons plans are over.

Effective Technology Professional Development. There were seven practices identified so far that that research revealed to have a positive effective for professional development. In addition to these seven practices, there are three additional practices specific to instructional technology professional development. Teachers learn best when there is tiered training

(beginner, middle, expert) with different modes of delivery (Schrum & Levin, 2013). It is also important to keep a focus on student learning instead of putting too much emphasis on the device

(Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

Hutchinson (2012) involved 1441 literacy teachers in the United States in a mixed methods study designed to identify characteristics that would contribute to effective professional development for integrating technology into instruction. This study was conducted using a survey with 69 Likert Scale questions, 11 multiple choice items, and eight openended responses.

He identified four effective characteristics for technology integration training: time to explore/prepare for instruction, access to equipment before/after training, continuous access to knowledge/knowledgeable trainers, and ongoing support.

These identified characteristics of effective integration training are similar to those identified in the previous section. Time to prepare and explore are aspects of contextualized, focused, and reflective training, access to equipment is an example of jobembedded training, and continuous access to knowledgeable trainers and ongoing support is an example of how a community can support the professional development.

In Hutchinson’s (2012) study, participants who identified time to explore/prepare for instruction as a characteristic, stated that they felt their learning experience would benefit from

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 32 more time to practice concepts between sessions and then the opportunity to discuss as a small group. They also requested longer, more indepth sessions instead of short workshops.

Regarding their access to equipment, 43.2% of participants argued that they needed the opportunity to manipulate the device during training instead of just visual demonstrations.

The majority of the teachers in this study (56.8%) reported that they needed better models of possibility for what integration should look like in a classroom. Hutchinson (2012) found that having access to trainers who can give specific details for scaffolding knowledge and examples of application of concepts increased the efficacy of the learning experience. In fact, 43.2% of educators identified ongoing support following training as a need, and also identified online tutorials, multiple exposures, and a combination of individual and small groups as specific ideas for improving the process. This information is consistent with the practices identified in the previous section and Transformational Learning Theory. This suggests that educators need time allocated to incorporate and reflect upon new knowledge before assimilating it into their existing beliefs and experiences (Webster & Wright, 2009; Gable & Burns, 2005).

Barriers to Technology Integration Professional Development. A great deal of the literature older than 10 years ago referred to access and cost of technology as the greatest obstacles to successful integration. With recent advances in technology and access to lowcost or free software, this has become less of an issue for schools. More recently, there were six general barriers identified for educators striving to integrate technology into their classrooms: resources, institutional knowledge, subject culture, attitudes and beliefs, knowledge and skills, and assessment (Hew & Brush, 2007).

Simply having resources within a highaccess classroom is not an indicator there will be

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 33 successful integration ( O’Brien & Scharber, 2010). On the other hand, open access to training alone is not a predictor of successful implementation (Ertmer & OttenbreitLeftwich, 2010).

Only through respecting beliefs and teaching practical use of the device will schools have the greatest impact on the efficacy of technology integration in classrooms, and, in turn, on student learning (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). Kadijevich (2012) observed that there are three different knowledge types within his Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (or TPCK) model: content knowledge to teach, pedagogical knowledge to apply, and technology knowledge to empower the other two (p. 28).

Kadijevich observed the main reason teachers do not implement technology in their classrooms is due to a lack of domain knowledge in technology. Since educators today must have knowledge in all three areas to be effective, schools must make handson learning, experimentation, access to equipment, and ongoing support priorities in any professional development planning (Swain & Pearson, 2003).

Wood, Mueller, Willoughby, Specht, and Deyoung, (2005) suggested that teachers must have constant opportunities and an open environment to voice concerns, experiences, and gaps in their learning. They conducted a study involving 54 elementary and secondary school teachers to gather data on possible obstructions. Barriers they observed were support issues (access to quality training), human resources (insufficient amount of technology support), material resources (access to devices), training and professional development (offerings), and administrative and parental support. When considering all of these barriers, the greatest problems were access to a device and quality training.

Impact of Devices. When weighing the importance of access to a device and quality

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 34 training, it is worth noting a key study performed by Fairlie and Robinson (2013) for the

National Bureau of Economic Research. In this study, 1123 students from 6th to 10th grade took part in a study to determine the influence of a device on student learning. Half of these students were given computers to take home for the year, and the other half were not. Neither the students nor the teachers were given any form of training. At the end of the school year, they observed that having a device had no effect on student grades, test scores, credits, attendance, or discipline. The presence of a device without training did not influence student learning. Access to technology is important, but it is not the sole differentiating factor. It is a necessary condition, of course, for increased instructional technology use in classrooms, but, alone, it is insufficient.

Responding to these highaccess/lowuse environments, Prensky (2012) suggested administrators encourage teachers to focus on innovation before training them on the devices.

His reasoning was that a school that purchased the student devices, and then attempted to find uses would have outdated devices by the time the teachers began using them effectively.

Prensky suggested a step in the process called “imagucation” (p. 2). Imagucation involves taking the last few moments of every class period a year before device implementation to have a conversation with students about what they could have done differently to increase student learning if all participants had personal devices. Prensky suggested that having teachers and students go through this thought process could be more educational than actually using the devices during the first year of implementing student devices.

Online Professional Development. While a great deal of research on general professional development can be applied to the context of training specifically for instructional technology, there is a lack of research into one aspect in use today. The use of online

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 35 professional development for educators (Desimone, 2009) is one that is gaining popularity, but the efficacy is yet to determined. Russell, Carey, Kleiman, and Venable, (2009) performed a study in which they compared the effects of facetoface learning with online learning for a group of mathematics teachers. While both formats showed positive outcomes, teachers who had taken the online professional development were more likely to participate in further training due to the asynchronous (and convenient) nature of the learning. Reeves and Pedulla (2011) identified multiple factors that maximized satisfaction among the online participants: number of hours of the training, quality feedback from the facilitator, rigorous online discussion among participants, clarity of participant expectations, availability of technical support, clear facilitator expectations, quality of course content, and friendliness of the online learning management system.

Blended Professional Development. Another aspect of professional development specific to the context of technology integration is blended learning. B lended professional development can be defined as a combination of online and facetoface instruction where learners are connected (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004). Garrison and Kanuka stated that this combination of onsite and online instruction resulted in a transformation in teaching practices.

The blended combination of instruction was especially powerful because participants reaped the benefits of the connection they had with a community of learners untethered by location. The energy and spontaneous nature of facetoface interaction combined with the reflection and discussion potential of online learning had the potential to multiply the learning experiences beyond what was possible within only one learning environment.

Owston and Wideman (2008) performed a twoyear study involving mathematics,

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 36 science, and technology teachers who experienced professional development in a blended learning environment. During the online portion, educators were asked to respond to posted articles within a class discussion, and post reflective journal entries every two weeks. They concluded that the blended environment had a positive effect on teacher attitude and showed a significant increase in content knowledge. In some cases, there was a transformation of classroom practice that could be attributed to the blended learning experience.

SelfDirected Learning Models. As mentioned previously, Gaible and Burns (2005) identified professional development as having three different modes: standardized, sitebased, and selfdirected. Schrum and Levin (2013) and Hedberg (2011) found that some of the most successful schools and districts were not only differentiating by using all three of these modes.

They were also by dividing training into levels (beginner, intermediate, advanced) and learning style (online, onsite, small group, oneonone). It was observed that the schools that took the time to survey and involve staff in the planning and execution of learning options were the ones who experienced the most success with teacher satisfaction (Schrum & Levin, 2013). Hedberg

(2011) reported that teachers involved with professional development of this type showed evidence of greater “personal efficiency, pedagogy, practice, increased awareness of individual student learning needs, and increased focus on interaction for students” (p. 1415).

Since many school environments have not provided teacher training that has been successful in assisting educators in implementing technology integration (Lawless & Pellegrino,

2007), some teachers have found that they are able to increase their capacity by using technology to teach themselves, share knowledge, and embrace a leadership role within their schools

(Schrum & Levin, 2013). Teachers who used social media tools, such as Twitter, were found to

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 37 be more willing to attempt implementation first, and often fulfilled a crucial role in the learning environments by bringing in new ideas from educators outside the school district (Forte, 2012).

Wright (2009) argued that Twitter was an obvious tool for educators since it allowed them to be selfdirected and ultracontextualized using education/subject specific hashtags.

1

Additionally,

Wright (2009) stated that the selfdirected nature of Twitter took away a possible stigma of the professional development offerings suggesting that the teacher had a deficiency and needed to be

“developed.” Encouraging Twitter for contextualized learning allowed an educator to be selfdirected as they maintained an updated body of knowledge and strategies.

Technology Training and Transformational Learning Theory

Much of the research covered in this section was consistent with the research shared on

Transformational Learning Theory. While it could be argued that schools have been using ineffective practices for engaging educators in learning experiences for many years (Sawchuck,

2010), the need for highquality training is great if teachers are going to increase engagement and efficacy through the use of technology (C. Dodson, personal communication, November 12,

2015). The changing landscape and culture of teaching has resulted in highaccess, but lowuse learning environments where students have equal access to technology, but unequal access to quality instruction ( Wood, Mueller, Willoughby, Specht, & Deyoung, 2005) . This makes it even more important for school leaders to offer professional learning experiences that will respect their teachers’ learning style, beliefs, and level of need (Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

It is also consistent with Transformational Learning Theory that schools who give educators the opportunity to reflect and participate in surveys are the most successful (Schrum &

1 On Twitter, a hashtag begins with a #, and is a method for grouping ideas so that they are searchable.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 38

Levin, 2013) . Prensky’s (2012) Imagucation exercise is particularly applicable to this theory by allowing the educator to draw upon his or her prior experiences each day and spend time projecting and speculating forward as to how their practice will change. Even more connections can be made between this theory and the research on teacher training within blended learning environments. For example, when teachers were asked to identify and share articles with colleagues instead of simply reading the materials assigned by their instructor, it allowed the educators to find articles they personally identified as useful within the overall topic (Garrison &

Kanuka, 2004).

Standards and Measurement of Professional Development

While researchers have generally agreed on what effective professional development looks like, it has proven much more difficult to measure the efficacy and overall impact (Martin,

Strother, Beglau, Bates, Reitzes, & Culp, 2010). Some researchers have focused their efforts specifically on investigating effective implementation of instructionaltechnology professional development (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). In their review, Lawless and Pellegrino recommended a threephase approach to designing evaluations that look at the quality and effectiveness of these learning experiences. They recommended an examination of the overall professional development design to help develop a systematic understanding of its particular characteristics. They also suggested examining the relationship between program characteristics and teacher outcomes, and also the effects on teachers and students. They felt that looking at these three aspects could provide a logical progression of the potential impact of the training and allow for “an examination of how variation among key characteristics at one level affects variation in important outcomes at the next level” (p. 602). Basically, having clear standards for

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 39 teacher outcomes allowed participants to measure their individual growth and progress.

The International Society for Technology in Education (2014) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to assist teachers and educational leaders in creating powerful connections among all learners. Through partnerships with over 100,000 educators all over the world, ISTE has created the definitive standards for learners, teachers, leaders, and coaches.

ISTE has not formally published their process for determining standards (C. Sykora, personal communication, July 2, 2014). It is based on a process developed by the Council for the

Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), formerly NCATE. ISTE is one of 23 specialized professional organizations (including NCTM, NCTE, NAYEC and others) that belong to CAEP.

CAEP uses their standards to nationally recognize teacher preparation programs. The process includes writing teams made up of educators, learning scientists, assessment specialists, NGOs, government agencies, and other subject matter experts to draft standards and put them out for public comment. ISTE chooses to iterate drafts as they are refined based on comments and feedback. The process takes one year for each set of standards. Because innovations in technology happen so quickly, ISTE also calls on those who anticipate what the needs and skills will be in the future. The standards are aspirational, and focus on how technology supports instruction and learning.

The SAMR model is another standard widely used by schools today when measuring their professional development outcomes (Romrell, Kidder, & Wood, 2014). The SAMR model provides a framework that allows for the evaluation of student and teacher use of technology

(Puentedura, 2013). Puentedura identified four levels for technology integration: substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition. When technology was used to perform the same

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 40 task that was already possible without technology, Puentedura referred to this as substitution.

The highest level, redefinition, was when learners or teachers were able to perform tasks that previously could not be done. Using the SAMR level, Puentedura said that teachers and students could measure when they were enhancing teaching and learning (substitution and augmentation levels), and when they were transforming teaching and learning (modification and redefinition levels).

Conclusion

The research shows that there is a gap between the needs of teachers as adult learners and the professional development that they are receiving (Sawchuck, 2010). Within the literature review, there were seven practices identified that are most effective for professional development. Teacher training should be contextualized and jobembedded with time provided for reflection (Tillema, 2000). There should also be a community approach that respects teacher beliefs and works to move them from their current level (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). This can be achieved by surveying staff, focusing content, and ensuring there are methods in place to measure progress and make decisions based on data. In addition to these seven practices, there are three additional practices specific to instructional technology professional development.

Teachers learn best when there is tiered training (beginner, middle, expert) with different modes of delivery (Schrum & Levin, 2013). It is also important to keep a focus on student learning instead of putting too much emphasis on the device (Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

With technology continuously expanding its role in our society, and the existing divide among skillsets of teachers (Prensky, 2012), it is imperative that the divide between teachers is bridged so that all students have access to a teacher capable of using technology effectively to

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 41 amplify student learning (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). With prominent districts, such as Los

Angeles Unified School District (Herald, 2014) failing to find an effective plan for implementation, it is clear that school leaders need more guidance. Furthermore, case studies of schools who have effectively implemented technology and trained teachers can offer strong models of possibility. Focusing on standards such as those from the International Society for

Technology in Education (2014) and SAMR can give teachers a clear application for their skills.

These standards can also provide educators a method for measuring growth, and having a true impact on student learning in the the classroom.

The research methods described in the following chapter addresses the gap in teacher technology skills through a mixed methods case study of two districts awarded a top level grant from the state Indiana Department of Education’s Office of eLearning. This study discusses the methods used by these successful districts and compares these methods to the research from

Chapter Two. This information provides data and models of possibility other districts can use to

make decisions regarding their ability to plan, expand, and measure the introduction of classroom technology to improve student learning and engagement.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 42

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In this section, the specifics of the method for the study are expanded and detailed to provide an understanding of the procedures, instruments, sample, and the process of data collection and analysis. This case study used mixed methods because it required, both, quantitative and qualitative data in order to fully answer the research questions. This chapter also establishes validity and reliability for the research tools used (survey and observation tool) to gather information from both school districts.

R

2

R

3

Research Questions

R

1

How did two Indiana school districts that won the IDOE Innovation and Learning Grant prepare their middle school teachers to integrate technology?

How closely does the instruction within these schools align with the ISTET Standards?

How did teachers at these school describe their professional development, and how closely do these descriptions reflect the ten identified characteristics of effective professional development from Chapter Two?

Research Design

This mixed method case study explored the professional development offerings from schools who were the recipients of the Innovation and Learning Grant in the state of Indiana.

The goal was to investigate the topic of professional learning and instructional technology using a defined set of procedures (Yin, 2014). The research process involved exploring the relationship between the professional learning methods used by these districts and the ten practices identified in the literature review.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 43

The alignment of instructional practices with the ISTET standards allowed for a common comparison for the success of the teacher preparation. For example, it could be argued that a school with a closer alignment to the ISTET standards than another would likely have more effective professional development for teachers. Convergent parallel mixed methods were used to merge the data from the survey and classroom observations (quantitative) with the focus group data (qualitative) during the interpretation of the results (Creswell, 2014).

The rationale for pursuing a case study came from the criteria set forth by Yin (2014).

The work is attempting to explain how and why these districts were able to successfully implement instructional technology and this qualifies as a “social phenomenon.” Additionally, the research questions required an indepth examination a process that Yin (2014) identified as a justification for a case study. Second, there were a series of decisions made by these districts, and the study sought to understand why? and how? they were made. Third, there are multiple variables involved in the process of integrating technology, and it was necessary to triangulate data from multiple sources within each district.

This case study has an embedded multiplecase design (Yin, 2014) in that there are two districts examined with three different units of analysis (survey, classroom observation tool, and focus groups questions). The results from these units of analysis were treated separately and not combined into one collective pool of data for analysis. The logic for this multiplecase study was to predict comparable results (literal replication) between the districts.

Description of the Sample

The Indiana Department of Education (IDOE) Office of eLearning typically awards

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 44 grants based on three different levels. There are Innovation and Planning grants to allow schools to begin the process of determining their current levels of instruction and infrastructure, and provide them the resources to create a strategic plan for increased technology integration in their classrooms. The middle level grant is the Digital Learning Grant that awards schools with excellent technology integration plans the resources to begin a pilot or rollout of student devices.

Districts who are deemed to be at the highest level of instructional technology integration have the chance to receive the Imagining and Creating eLearning grant. This grant provided funding for these forwardthinking schools to provide models of possibility to other districts in the areas of digital content, customized learning, and flexible scheduling. In 2013, over 50 districts applied for this grant through an online application. Twentyfive districts were chosen to travel to the IDOE Office of eLearning to give a 10minute pitch. There were 16 districts chosen for this grant: digital content

2

(nine), customized learning (three), flexible scheduling

(four).

Two districts who received the Innovation and Learning Grant from the IDOE Office of eLearning in the area of digital content were chosen for this study. Rogers Middle School is located in Indiana and had 2705 students enrolled in 20132014. The district it belongs to has four elementary schools, a middle school, and a high school. According to the IDOE Compass website, 50.6% of students are in the free and reduced lunch population, and 94.5% of students are white. There are 15.2% of students who are in special education programs. Student

2 Digital content winners curated digital curriculum by standard for other schools to use. Customized learning winners piloted strategies for using technology to create an individualized learning experience for students. Flexible scheduling winners piloted the concept of eLearning on snow days.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 45 achievement scores have shown an increase over the past four years, with 70.9% of students passing ISTEP in the 20122013 school year.

Stark Middle School is located 24 miles from Rogers Middle School. This district served

3003 students in 20132013 (see Table 3.1). The school district it is part of has four elementary schools, a junior high, and a high school. According to the IDOE Compass website, 55.1% of

Stark Middle School students are on free and reduced lunch, and 89.8% report themselves as white. There are 14.7% of students who are in special education programs. Student achievement scores have shown a decrease the past three years with 68.4% of students passing in the

20122013 school year. The graduation rate has steadily increased over the past four years with

92.6% of students graduating in 20122013. These two school districts have similar demographics among the population they serve. However, the biggest difference is that the district to which Stark Middle School belongs graduates almost 18% more students per year.

This study was focused on the middle schools for both districts because this is where the

technology integration was focused initially. Both middle schools had 1:1 programs for multiple years, and the success of these programs is what helped them draw attention from the IDOE

Office of eLearning.

ASSIMILATING DIGITAL IMMIGRANTS 46

Table 3.1

Comparison of District Demographics

Enrollment (20132014)

Rogers Middle School

2705

Free and Reduced Population

(20132014)

50.6%

Ethnic Background (20132014) 94.5% white

Special Education (20132014)

% Passing ISTEP (20122013)

15.2%

70.9%

The Instruments

Stark Middle School

3003

55.1%

89.8% white

14.7%

68.4%

The FiveStar ISTET Survey and Classroom Observational Tool were designed to gather information about teachers' current levels of technology integration according to each of the five

ISTET standards. The focus group questions were created to elicit information about each of the ten identified practices for effective professional development from the literature review, and further information on the ISTET Standards. These three instruments were tested for content validity by an expert panel consisting of Brad Fischer, Melissa Pogue, and Lisa Cutshall.

Brad Fischer was the Director of Information Services at Danville Community Schools in

Danville, IN for 15 years. Brad has a bachelor’s degree in mathematics education from Ball